While browsing recently through the available back issues of Oz magazine I noticed a guide to gay slang that I didn’t recall seeing before. The underground magazines and newspapers of the 60s and 70s were a lot more tolerant of the nascent gay rights movement than their “straight” (ie: non-freak) counterparts. Oz magazine published pieces about gay rights, notably so in issue 23 which ran an extract from The Homosexual Handbook (1969) by Angelo d’Arcangelo among a couple of other features; the UK’s first gay magazine, Jeremy, advertised regularly in Oz and IT; later issues of Oz carried ads for another gay mag, Follow Up, and there’s a letter in one issue from a gay freak complaining about the state of the few gay pubs in London where the clientele was apparently not freaky enough. (His solution was to try and persuade them all to drop acid.) Arguments which still circulate today, between those who want to assimilate and those who prefer to remain separate from general society, go back a long way.

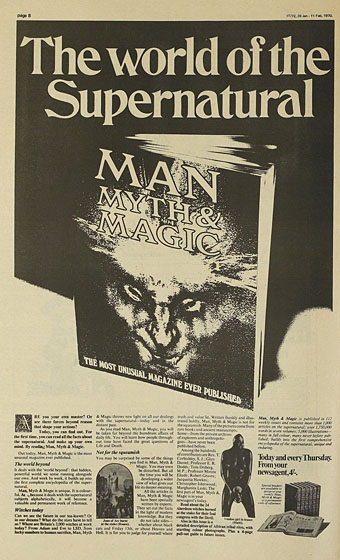

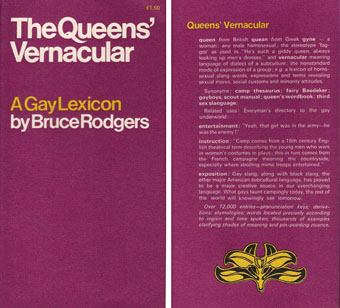

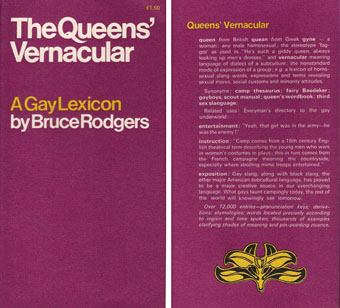

The gay slang guide was extracted from The Queens’ Vernacular: A Gay Lexicon by Bruce Rodgers (1942–2009), published in the US by Straight Arrow Books in 1972. Straight Arrow was affiliated with Rolling Stone magazine, later publishing two volumes of Wilfried Sätty’s art, and Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon. Rodgers’ book was reissued in 1979 as Gay Talk: A (Sometimes Outrageous) Dictionary of Gay Slang (Formerly entitled The Queens’ Vernacular) but has been out-of-print ever since, unsurprisingly since so much of it is now completely outmoded. That doesn’t make the content uninteresting, however. The phraseology may be ribald, obscene and offensive (misogynist, especially) but the book has been described as “the first serious dictionary of gay slang and the definitive gay American jargon resource”. Rodgers was a serious researcher with an interest in all forms of slang. Just as the Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1811) by Francis Grose gives a more-or-less unmediated insight into the lives of the working and criminal classes of 18th-century London, so Rodgers’ dictionary tells us something about the way gay people, especially gay men in the US, were talking to each other for much of the 20th century. What’s striking now about this truncated list is the degree to which so much of the language is obsolete—nobody under the age of 60 would use the term “queen” with such frequency—while the wider acceptance of porn has made once-esoteric terms like “golden shower” much more common. Notable by its absence is “queer” as a purely positive description (not reclaimed until the 1980s), and no mention of “twink” (which goes back to the early 60s) or “bear” (another term from the 80s).

There’s a tendency when looking at lists such as this to imagine a group of people using most of the terms all the time, but as with any form of slang this would be unlikely. The same goes for Polari or the handkerchief codes of the 1970s. As you’d expect from a document that’s 42 years old, some of the language that Rodgers collected tramples over many current sensitivities. •

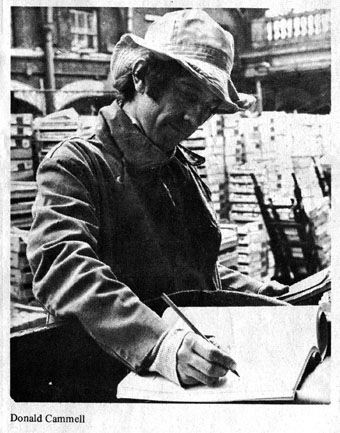

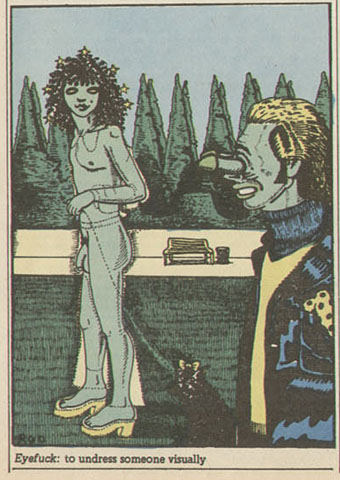

Illustration by Rod Beddall.

THE QUEEN’S VERNACULAR, Oz 46, Jan–Feb 1973

Gay slang has been coined and used by those within the gay subculture who themselves feel the most oppressed—the flagrant wrist benders, the screaming queens, the men who look like women, the women who don’t shave their moustaches.

It is a form of social protest, aimed at the establishment; it is also self-protective and self-defeating. Gay militants would like to see it go, and argue rightly that gay jargon is yet another link in the chain which holds the homosexual enslaved and oppressed—yet its widespread use and complex vocabulary indicate that gay liberation has still along battle in front of it. The selections which follow are taken from a Straight Arrow publication, The Queens’ Vernacular by Bruce Rodgers. The words are mostly American. Even the classic English phrase, “queer basher” is not included.

* * *

advertising 1. to dress in a sexually provocative manner. Gay maxim: “It pays to advertise.” 2. (camp) to pluck and then paint the eyebrows.

army style (mid ’60s) beating the cocksucker after the act.

bumping pussies the embarrassment of two homosexual men who find themselves too passive, active, or in other ways too similar to create a sexual situation. “He thought you and I were carrying on together—what would we do, bump pussies?”

cash-ass (from cautious) cynically applied to hustler who feigns coyness until assured of material gain. “He’s not shy, he’s cash-ash. Mention money and watch his cheeks light up.”

catalogue queen homosexual who collects physique magazines for masturbation purposes.

cheesy having the foreskin lined with smegma. Stale and musky smelling. “The sailor was so cheesy that I felt like asking him where be hid his crackers.”

chic the latest craze. Cruising the busy streets after the bars close is chic. Getting invited to an orgy is chic. Sucking men off in a public lavatory is not chic. Wearing pearls with grey flannel is not chic either, unless one is serving tea in a closet.

Continue reading “Gay slang from the 1970s”