I think of the area of magic as a metaphor for the homosexual situation. You know, magic which is banned and dangerous, difficult and mysterious. I can see that use of magic in the Cocteau films, in Kenneth Anger and very much in Eisenstein. Maybe it is an uncomfortable, banned area which is disruptive, and maybe it is a metaphor for the gay situation.

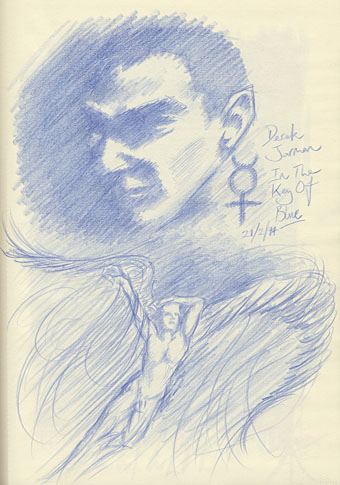

Derek Jarman, in conversation with Simon Field and Michael O’Pray, 1985

Derek Jarman’s face appears briefly in The Salivation Army (2002), a short history/memoir by Canadian artist Scott Treleaven concerning This Is The Salivation Army, a zine Treleaven produced with a small group of friends from 1996 to 1999. The film itself is credited as the ninth issue, and makes me sorry to have missed the zine in its original incarnation.

The season of Jarman films which is currently running in London is entitled Queer Pagan Punk, and will include a screening of Treleaven’s film next month, along with Glitterbug (1994). The phrase “Queer Pagan Punk” encapsulates the ethos of This Is The Salivation Army, and Treleaven’s narration describes the origin of his zine in a familiar sense of unfocused rage, and also the alienation he and his friends felt towards the vapidities and conformity of contemporary gay culture. Being someone who’s always loathed clubbing, and the consumerist drivel that fills so many gay magazines, this is music to my ears; I just wish the zine been around in the 1980s. The shadow of the Temple of Psychic Youth—which was around in the 1980s—hangs heavily over this project; Derek Jarman had his own connections with PTV/TOPY, of course, being an ally of Throbbing Gristle, and later of Coil. The fanzine may have run its course but Treleaven continues to explore queer paganism in his artwork. The Salivation Army can be seen at Vimeo.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Just the ticket: Cabaret Voltaire

• Abrahadabra

• The art of Scott Treleaven