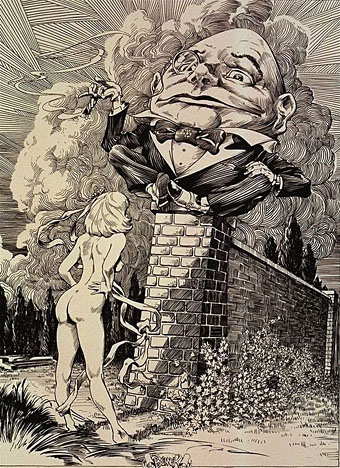

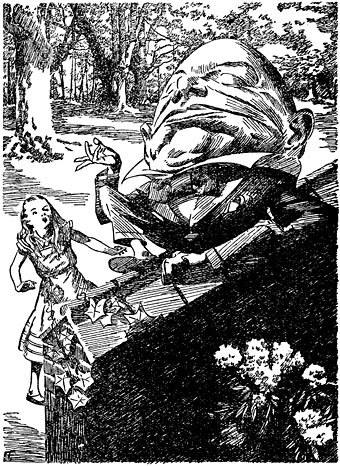

Humpty Dumpty by EB Thurstan (1930).

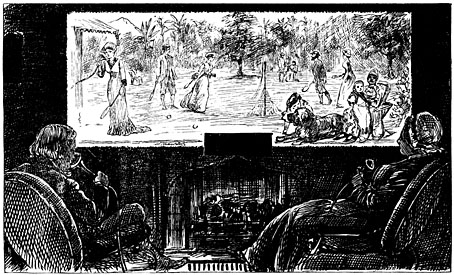

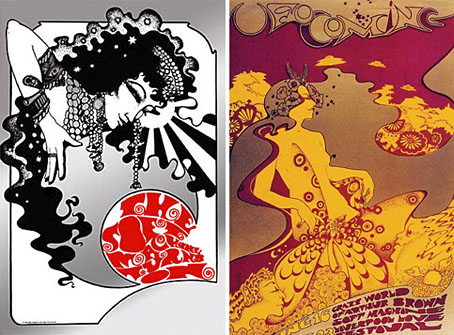

A preoccupation of the past couple of weeks has been Lewis Carroll’s Alice books as I’ve been working on an Alice in Wonderland project which I’ll unveil shortly. Looking around at some of the numerous visual interpretations of the stories I came across two portfolios I hadn’t seen before by comic artist Frank Brunner. These are from the late Seventies, and typically for that decade they work an erotic twist on the books by adding ten years to Alice’s age whilst depriving her of clothes. Nudity aside, Brunner’s drawings don’t depart from tradition very much—or add much, for that matter—but I did notice that he’d based his Humpty Dumpty figure on an earlier version by illustrator EB Thurstan.

Humpty Dumpty by Frank Brunner (1978?).

The reason Thurstan’s Humpty is so familiar is that I’d borrowed it myself for one of the many appearances by the character in the Lord Horror comic series, Reverbstorm. Humpty’s presence there would involve too much explanation so you’ll have to be satisfied with the character who explains Jabberwocky remaining inexplicable. As for Brunner’s drawings, you can see coloured versions on his website.

Humpty Dumpty from Reverbstorm #3 (1994).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alice in Wonderland by Jonathan Miller

• The Illustrators of Alice