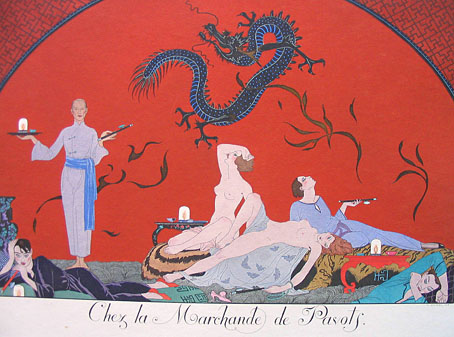

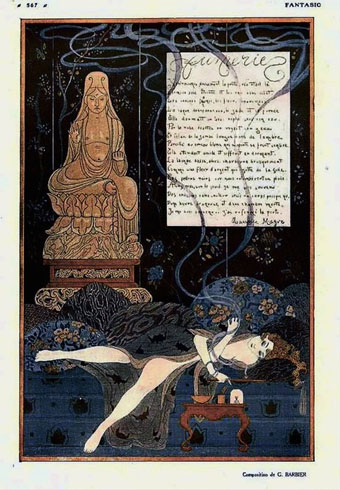

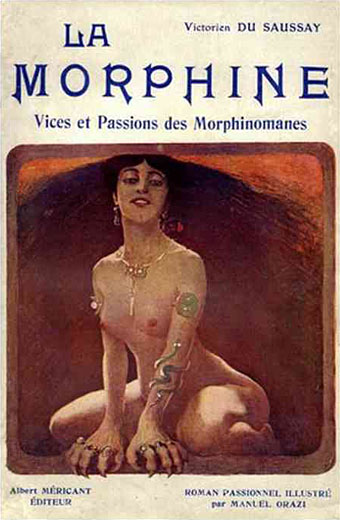

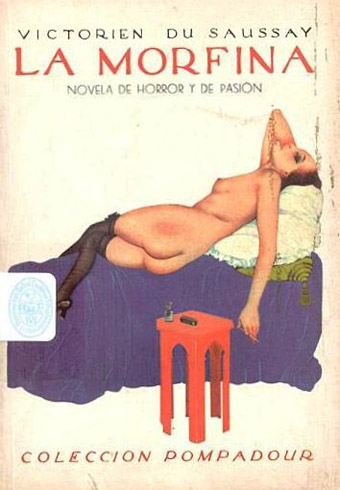

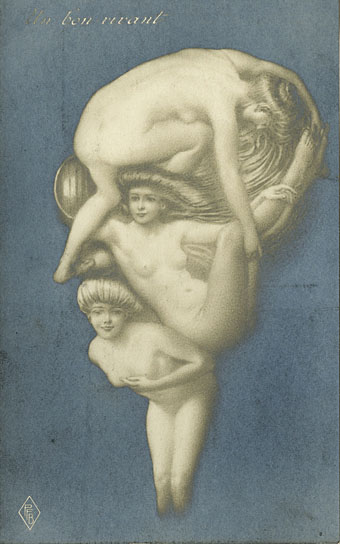

The Arcimboldo Effect again. An undated postcard from the image section of A Virtual Wunderkammer: Early Twentieth Century Erotica in Spain.

“I took George Clinton and Bootsy Collins to the Battle Station for the first time, and they left feeling like they’d just had a close encounter,” said the bassist and music producer Bill Laswell, who met Rammellzee in the early 1980s and remained one of the few people who saw him regularly.

• Also in the NYT: China Miéville on Apocalyptic London: “Everyone knows there’s a catastrophe unfolding, that few can afford to live in their own city. It was not always so.” Reverse the perspective and find Iain Sinclair writing in 2002 about Abel Ferrara’s The King of New York: “A memento mori of the century’s ultimate city in meltdown.”

• The Inverted Gaze: Queering the French Literary Classics in America by François Cusset. Related: Glitterwolf Magazine is asking for submissions from LGBT writers/artists/photographers.

• The vinyl releases of Cristal music by Structures Sonores Lasry-Baschet continue to be scarce and unreissued. Mark Morb has a high-quality rip of the group’s No. 4 EP here.

• Henri’s Walk to Paris, the children’s book designed by Saul Bass in 1962, is being republished. Steven Heller takes a look.

As the critic Jon Savage points out, even rock’n’roll’s very roots, the blues, contained a weird gay subculture. The genre was home to songs such as George Hannah’s Freakish Man Blues, Luis Russell’s The New Call of the Freaks, and Kokomo Arnold’s Sissy Man Blues. “I woke up this morning with my pork grindin’ business in my hand,” offers Arnold, adding, “Lord, if you can’t send me no woman, please send me some sissy man.”

Straight and narrow: how pop lost its gay edge by Alexis Petridis

• David Pelham: The Art of Inner Space. James Pardey interviews the designer for Ballardian.

• BBCX365: Johnny Selman designs an entire year of news stories.

• Sarah Funke Butler on Nabokov’s notes for Eugene Onegin.

• Leslie S. Klinger on The cult of Sherlock Holmes.

• How piracy built the US publishing industry.

• The Light Pours Out Of Me (1978) by Magazine | Touch And Go (1978) by Magazine | Motorcade (1978) by Magazine | Feed The Enemy (1979) by Magazine | Cut-Out Shapes (1979) by Magazine.