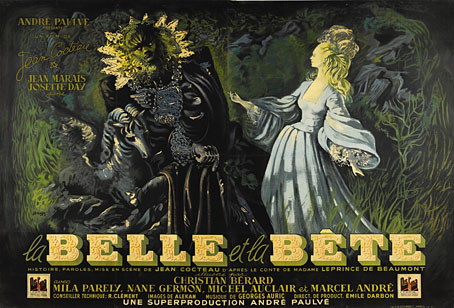

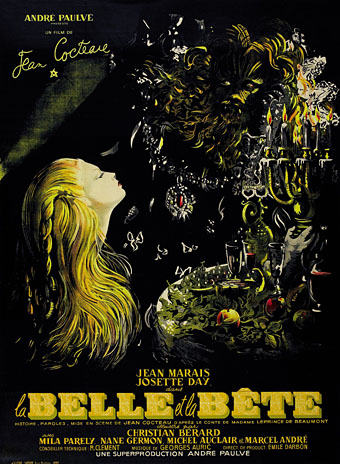

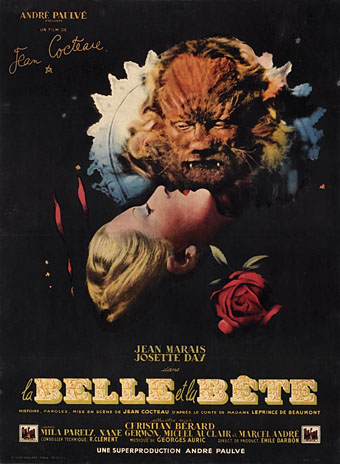

Continuing the Cocteau theme, this fascinating film remains (for the time being) unavailable in a better copy despite its artistic all-star cast. 8 x 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements (1957) can be regarded as a follow-up to Hans Richter’s Surrealist anthology Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947), the directorial credit this time being shared between Richter, Jean Cocteau and Marcel Duchamp. The latter famously quit the art world to devote more time to chess-playing so his involvement with a chess-based fantasy (self-described as “a fairytale for grownups”) isn’t so surprising:

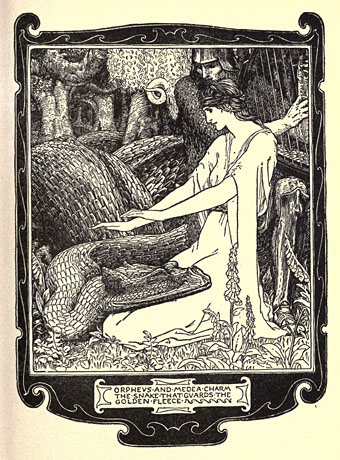

It explores the realm behind the magic mirror which served Lewis Carroll 100 years ago to stimulate our imagination.

The cast comprises famous friends including Cocteau himself, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Paul Bowles, Fernand Leger, Alexander Calder, Duchamp, and, in the Venetian episode, Peggy Guggenheim in her favourite sunglasses. In places it’s closer to Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) than Dreams That Money Can Buy, especially since Anger’s film was another assemblage of unique personalities. One detail I’ve not seen remarked upon elsewhere is the presence behind the camera of Louis & Bebe Barron who assisted with the sound. The Barrons are better known today for their still astonishing all-electronic score for Forbidden Planet (1956). Watch 8 x 8 at Ubuweb or YouTube.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dreams That Money Can Buy