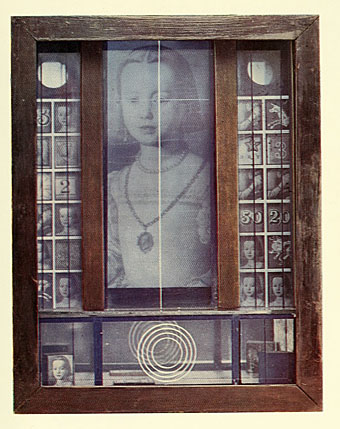

René Magritte as portrayed by Patrick McDonnell.

René Magritte died in 1967, the year Eric Duvivier’s La femme 100 têtes appeared in French cinemas. Magritte is even less visible cinematically than Max Ernst, IMDB lists a couple of documentaries and nothing else. There are trace elements elsewhere, notably the Magritte and de Chirico influence in Bertolucci’s Borges’ adaptation The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), but the artist’s arresting visual imagination has always found more of a welcome on book covers than cinema screens.

One exception is David Wheatley’s drama documentary René Magritte (1976), yet another work you won’t find listed at IMDB. This was Wheatley’s graduation film which the BBC screened in a 30-minute version (shorn of some apparently clunky dialogue scenes) in 1979, and which secured for Wheatley a place as a regular director for the BBC’s Omnibus and Arena arts programmes. I saw the 1979 broadcast, and caught it again a decade later when one of the channels was having a season of Magritte-related programming, something that’s impossible to imagine in today’s debased television landscape.

For a student film it’s a stunning piece of work, taking a similar approach to Eric Duvivier in bringing to life many of the artist’s more famous pictures: a window shatters to reveal the scene behind it painted on its panes, a mountain hovers ponderously over the sea, a dove made of clouds flies across a stormy sky. Between the artworks there are short biographical scenes. There’s a sole version of the film on YouTube that remains watchable despite being a low-quality recording from video tape that’s also hacked into three parts and subtitled in Danish.

Looking for more information about David Wheatley it was dismaying to find he’d died in 2009, aged 59. Leslie Megahey—a cult TV director of mine—wrote an obituary for the Guardian where he describes some of Wheatley’s other productions including the Arena film Borges and I (1983)—as far as I’m aware the only British TV documentary about Jorge Luis Borges—and Wheatley’s first feature film, an adaptation of Angela Carter’s The Magic Toyshop (1987). I recall enjoying the latter, produced at a time when the success of The Company of Wolves (1984) made it seem there might also be a place in the cinema for Angela Carter’s imagination; we know how that worked out. The Magic Toyshop doesn’t seem to have had a DVD release so good luck to anyone searching for it. As for René Magritte, if anyone runs across a better online copy be sure to leave a comment.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Public Voice by Lejf Marcussen