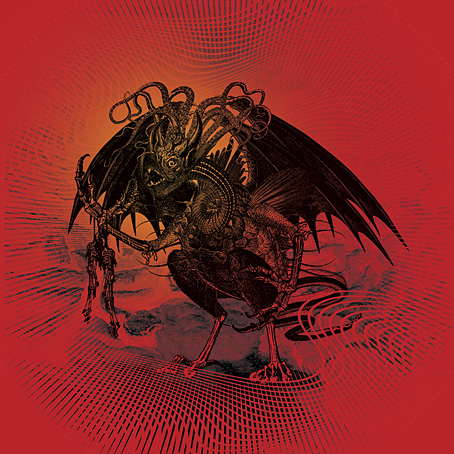

The Jabberwock (2010).

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

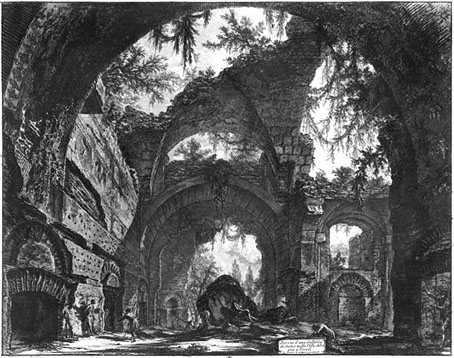

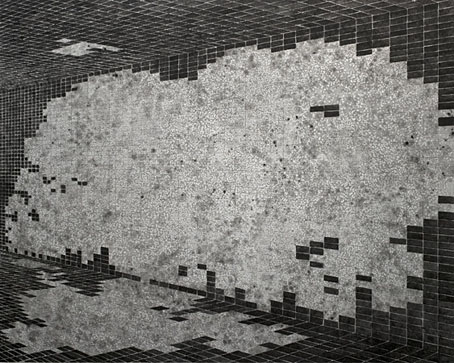

The past month has been inordinately busy which has meant all the fine plans for a 2011 Coulthart calendar have been set back further than intended. No prizes for guessing the theme this year. This picture made its web debut last weekend at Alicenations, a Brazilian site devoted to all things Carrollian. Lots of splendid artwork on the rest of their page, including some of Jan Svankmajer’s Alice collages and some familiar bestiary hybrids. As to the calendar, I’m pleased to say the series of pictures is starting to feel halfway finished so I may have the whole thing completed and uploaded to CafePress sometime next week. Keep your vorpal blades crossed. In the meantime, here’s a picture detail, and while we’re on the subject, let’s not forget Terry Gilliam’s first feature film or the 1968 single from Boeing Duveen & The Beautiful Soup. (Given a choice I prefer the B-side, Which Dreamed It?)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alice in Acidland

• Return to Wonderland

• Dalí in Wonderland

• Virtual Alice

• Psychedelic Wonderland: the 2010 calendar

• Charles Robinson’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

• Humpty Dumpty variations

• Alice in Wonderland by Jonathan Miller

• The Illustrators of Alice