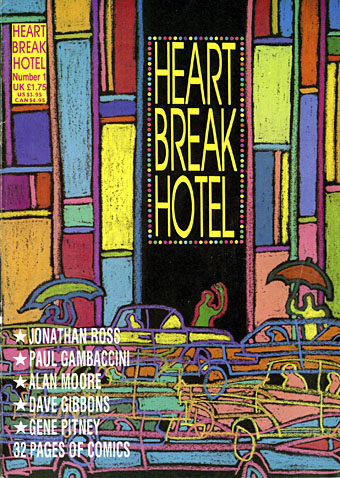

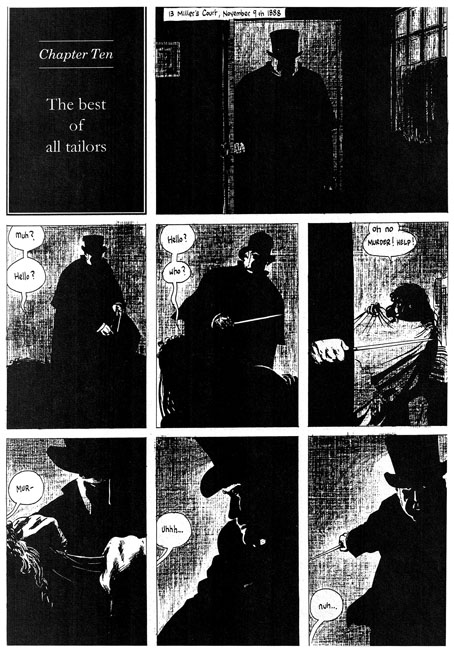

Number One: Teen Angels in Anguish. Cover by Barry Kamen.

Among the recent uploads at the Internet Archive is a complete run of Heartbreak Hotel, a British magazine six issues of which were published in 1988. (More or less…I think the first issue may have appeared at the end of 1987.) Heartbreak Hotel differed from other bi-monthly publications by being predominantly a comics magazine, but it also differed from other comics magazines by a) having the contents of each issue themed to follow a different musical genre, b) running articles by and interviews with people who had little or no connection to the comics world, and c) being a lot more openly sympathetic towards gay men and lesbians than any other magazine aimed at a general readership. The latter stance was a political one in 1988. This was the year when the Thatcher government, growing hubristic after a third election win, passed a Local Government Act whose notorious Section 28 prevented authorities from “promoting homosexuality”. The clause was designed to prevent Labour-run councils from funding gay and lesbian support groups, as well as to stop teachers from mentioning homosexuality in sex education lessons. The editors of Heartbreak Hotel, Don Melia and Lionel Gracey-Whitman, were a gay couple, so the magazine stood against the repressive atmosphere of the time without being too polemical or too serious. The polemic was more overt in affiliated publications Strip AIDS, a benefit comic for the London Lighthouse (a residential and daycare centre for people with AIDS), and AARGH (or Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia), a collection of comics taking a stand against Section 28 which was the first publication from Alan Moore’s Mad Love imprint.

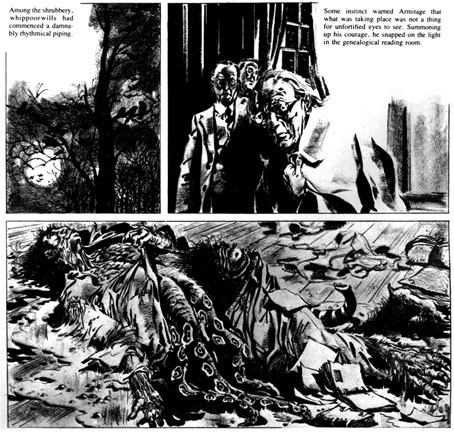

The other notable feature of Heartbreak Hotel was the attention it gave to new artists, to women artists, or to people who weren’t drawing generic action/adventure strips. The first two issues appeared while I was working on the last pages of my adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu so I sent the magazine some sample pages and was subsequently invited to meet the editors at the launch of the next issue in London. I spent a somewhat nervous weekend in the capital; this was my first introduction to the wider comics world, and my introversion in those days was a lot more pronounced among strangers than it is today. I met Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie for the first time (separately—they weren’t a couple at that time), and was amused when Don made a point of telling me that he and Lionel were gay, something he evidently felt he had to declare even though it had been (for me, at least) quite obvious from the editorial stance of Heartbreak Hotel, as well as the camp graphics scattered throughout the magazine’s pages, and the fact that the publisher was co-named “Willyprods”.

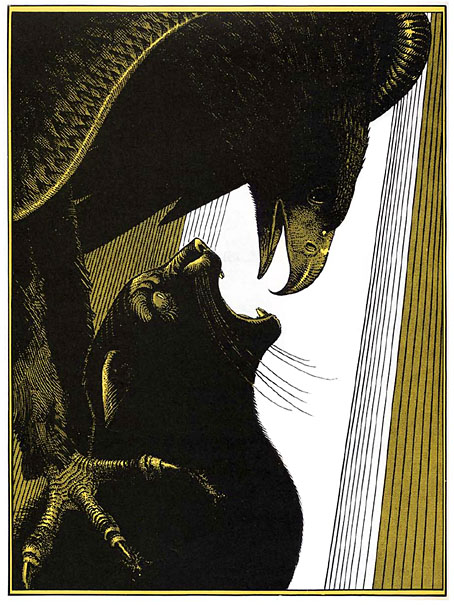

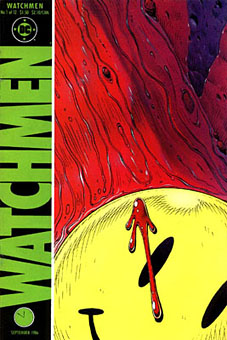

Dave Gibbons spills the beans in issue one.

The format of the magazine was established in the first issue: five or six strips based on songs that suited that issue’s theme, together with interviews or features, some of which also matched the theme. “Spill It!!” was a regular feature in which a different artist had a page to create an autobiographical piece in strip form, and there was also a column about comics and related matters by artist/writer Trina Robbins. I’d initially hoped to draw something for the psychedelic issue but by the time I posted my photocopies that number was already being prepared for print. I did turn up in the fourth issue, however, in a short news piece which announced the publication of the Caemaen Books edition of my Haunter of the Dark strip.

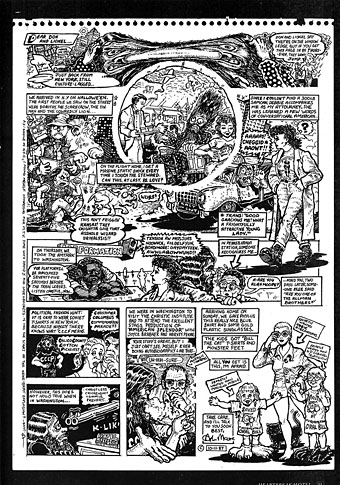

Also from issue one, Alan Moore recounts his trip to the USA.

A more important outcome from my journey to London was Lionel’s offer to run The Call of Cthulhu in BLAAM, a spin-off comic that Willyprods/Small Time Ink was planning. Heartbreak Hotel had been inundated with work by talented newcomers so rather than make them wait for a slot in the parent magazine the editors decided to launch another title to provide an additional outlet for new creators. Lionel had been very impressed with my Lovecraft story, and also assisted with its conclusion when he suggested that I add an extra page to help the pacing near the end, something I did, and which I’ve been grateful for ever since. The first issue of BLAAM, printed on tabloid-size newsprint sheets, came bundled with issue five of Heartbreak Hotel. The idea was that BLAAM would continue separately as a free publication thanks to a combination of low production costs, advertising, and Don Melia’s contacts at Titan Distribution. This was all very exciting, especially when two more issues of BLAAM appeared soon after. My strip was slated to run in number four or five but Willyprods/Small Time Ink didn’t publish anything more after December 1988. I was disappointed by this but not for long. A year later I’d started working on the Savoy comics, and Steve Bissette offered to publish the Cthulhu strip in Lovecraft Lives, a book he was planning for Kevin Eastman’s new enterprise, Tundra Publishing. That one didn’t work out either—the stars weren’t right for a variety of reasons—but all this attention, and the enthusiasm shown by everyone involved with Heartbreak Hotel, made the comics world seem like a good place to be. For a while, anyway.