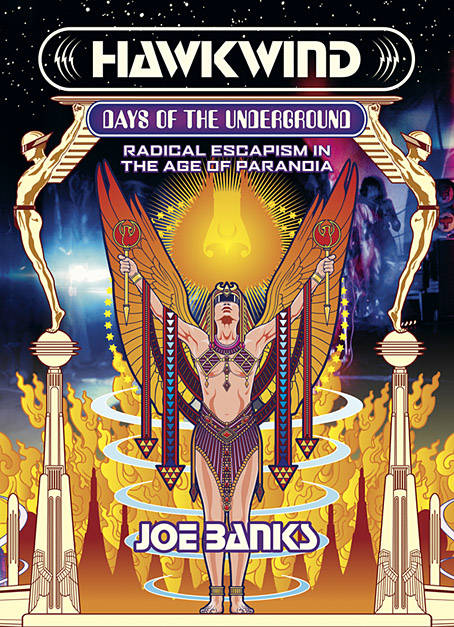

As mentioned at the weekend, Joe Banks’ account of the first ten years of Hawkwind will be published by Strange Attractor Press later this year with a wraparound cover of my design. I never expected to be doing anything else for Hawkwind after moving on to other things in 1985, but it was the group’s first decade of music that fuelled the drawings which brought me to their attention, so this cover design brings everything full circle. The earliest of my Hawkwind drawings dates to 1979 which means this cover is also an anniversary piece.

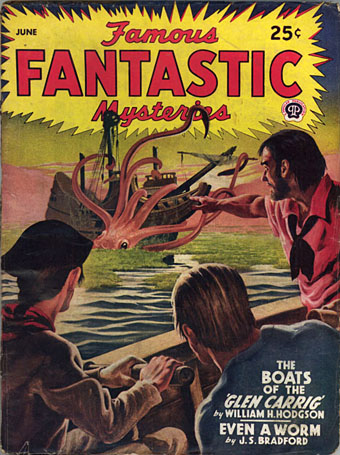

The design combines Barney Bubbles’ Space Ritual template with elements of the art he created before and afterwards, notably the inner and outer sleeve of Doremi Fasol Latido, and the futuristic Art Deco of his tour poster for The “1999” Party. All the Bubbles Hawk-art up to and including Space Ritual is a blend of the ancient (Egypt, tribal motifs, characters that resemble pirates or barbarians), the previous century (Art Nouveau in particular), and the far future as depicted in comics and pulp magazines. I wanted to reflect this blend without being too imitative of the details, so the cover works a variation on Space Ritual, with a similar hieratic woman as the focus, and a margin of stylised flames separating the foreground from Laurie Lewis’s photos of the band (the latter are unused shots from the same session used for Space Ritual).

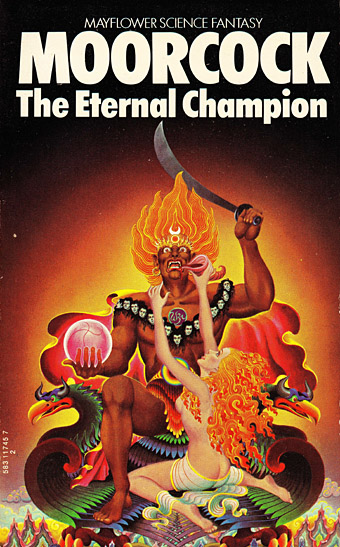

Art by Bob Haberfield, 1970.

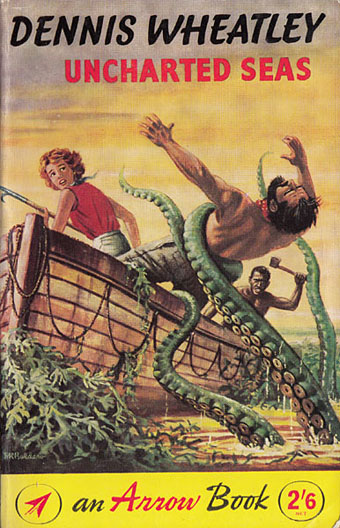

All the background elements run across the wrap but this hasn’t been revealed yet so you’ll have to wait a while to see the full design. The flames are based on Tibetan designs in a nod to the ancient side of the equation, as well as Bob Haberfield’s covers for the Moorcock novels published by Mayflower in the early 70s, many of which featured art derived from Tibetan Buddhism. (And one of the Mayflower Moorcocks, The Black Corridor, is the origin of the monologue of the same name on Space Ritual.) The full wrap shows a futuristic city whose Frank R. Paul-derived architecture is either on fire or menaced by a wall of encroaching flames. Many of Hawkwind’s songs of the period concern flight from cities or from the Earth itself—Born To Go, Time We Left (This World Today)—so the back cover also has a number of vehicles fleeing the scene: the radical escapism of the book’s subtitle in literal form. “Sign my release from this planet’s erosion,” as Nik Turner sings in Brainstorm.