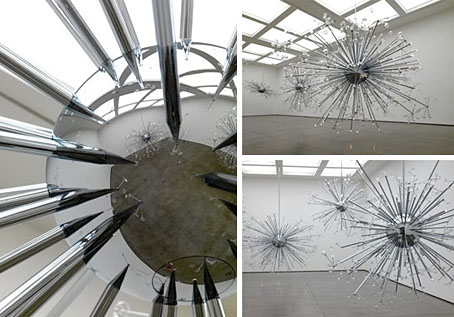

Island Universe (2008).

Island Universe is a new work by American artist Josiah McElheny at London’s White Cube gallery. McElheny’s recurrent use of glass and mirrors would be enough to capture my attention anyway—I particularly like the Modernity piece below—but Island Universe also features a specially-commissioned sound accompaniment by one of my favourite musicians, Paul Schütze.

Modernity circa 1952, Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely (2004).

McElheny collaborated with cosmologist David Weinberg for Island Universe to create abstract sculptures that are scientifically accurate models of Big Bang theory as well as illustrations of the ideas that followed the general acceptance of the theory. The varying lengths of the rods are based on measurements of time, the clusters of glass discs and spheres accurately represent the clustering of galaxies in the universe, and the light bulbs mimic the brightest objects that exist, quasars. Island Universe proposes a set of possibilities that could have burst into existence depending on the amount of energy or matter present at the universe’s origin.

I can’t help but compare that description of McElheny’s new work with another exhibition that opened this week, TH.2058 by Dominique Gonzales-Foerster which will be filling Tate Modern’s vast Turbine Hall for the next few months. Josiah McElheny extrapolates from documentary fact and creates something beautiful at the same time. Ms Gonzales-Foerster borrows from pre-existing works of written and filmed science fiction and has to rely on those works to sustain much of the interest:

It rains incessantly in London – not a day, not an hour without rain, a deluge that has now lasted for years and changed the way people travel, their clothes, leisure activities, imagination and desires. They dream about infinitely dry deserts.

This continual watering has had a strange effect on urban sculptures. As well as erosion and rust, they have started to grow like giant, thirsty tropical plants, to become even more monumental. In order to hold this organic growth in check, it has been decided to store them in the Turbine Hall, surrounded by hundreds of bunks that shelter – day and night – refugees from the rain.

A giant screen shows a strange film, which seems to be as much experimental cinema as science fiction. Fragments of Solaris, Fahrenheit 451 and Planet of the Apes are mixed with more abstract sequences such as Johanna Vaude’s L’Oeil Sauvage but also images from Chris Marker’s La Jetée. Could this possibly be the last film?

On the beds are books saved from the damp and treated to prevent the pages going mouldy and disintegrating. On every bunk there is at least one book, such as JG Ballard’s The Drowned World, Jeff Noon’s Vurt, Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, but also Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones and Roberto Bolaño’s 2666.

On one of the beds, hidden among the giant sculptures, a lonely radio plays what sounds like distressed 1958 bossa nova. The mass bedding, the books, images, works of art and music produce a strange effect reminiscent of a Jean-Luc Godard film, a culture of quotation in a context of catastrophe.

There’s a list of works used in the Tate installation, nearly all of which are far more stimulating artworks in their own right than the one which is hijacking them into its “culture of quotation”. I’m sure I can’t be the only person to think that the Tate would have been better served asking McElheny and Schütze to expand their work to fill the Turbine Hall instead. Those Island Universes could only get better if they were bigger.

Studies in the Search for Infinity (detail, 1997-1998).

• A PBS feature on Josiah McElheny

Update: Writer M John Harrison reviews TH.2058 for the Guardian and fails to be impressed:

It occurred to me that the biggest disaster in that room is the disaster for art. TH.2058 seems to finalise the hollowing-out of everything into the shallowest of semiotics. Foerster’s reading list is more powerful and important than her installation. Every one of the books on those bunk beds will give you a frisson that you don’t get from the show, so you would be as well just reading them for yourself.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth

• The Garden of Instruments