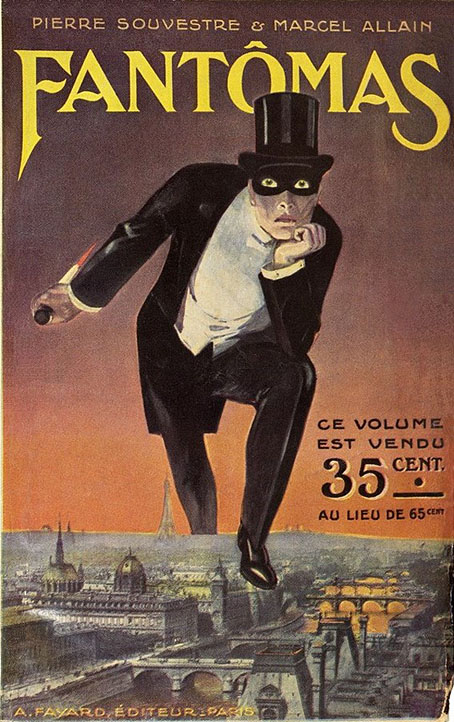

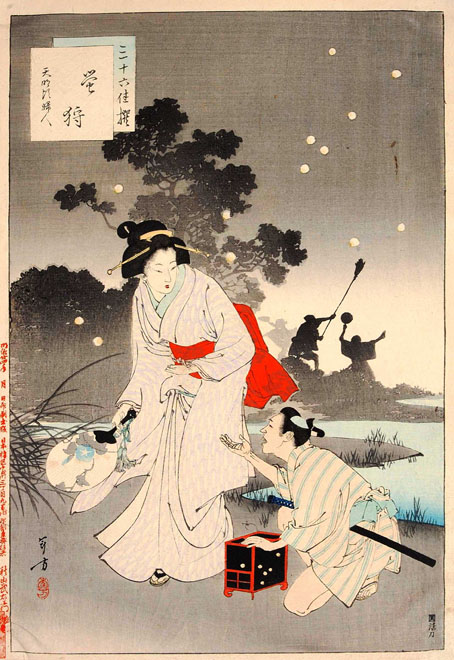

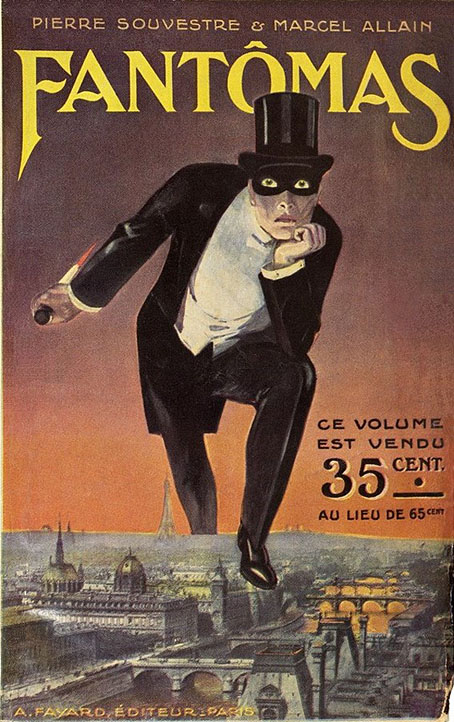

Uncredited cover art for the first publication, 1911.

The post title is a word apparently invented by James Joyce, one whose origin I’ve yet to discover. There may be some slight disparagement in its use of “enfant”, a suggestion that the Fantômas novels (or the films derived from them) were childish pleasures. If so, those childish pleasures had many supporters among the cultural avant-garde of Paris, as we’ll see below.

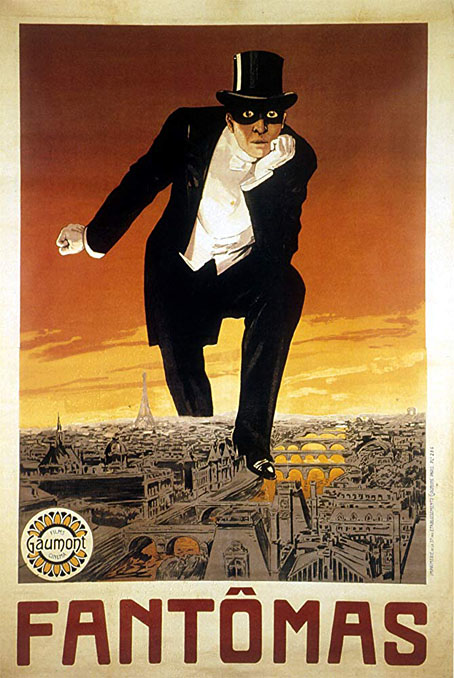

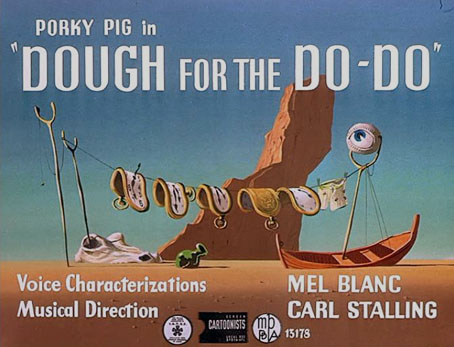

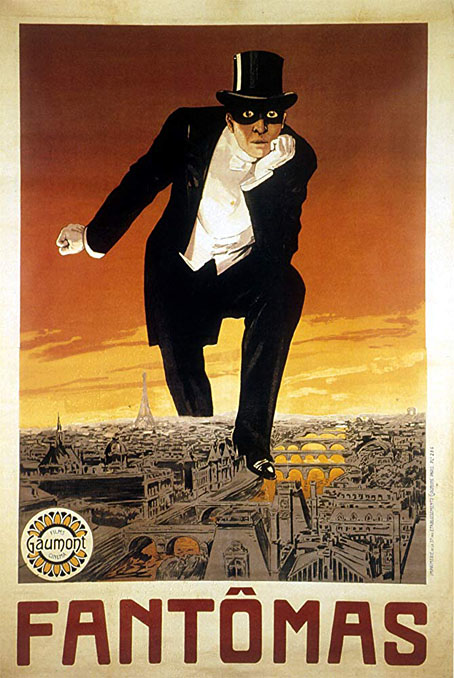

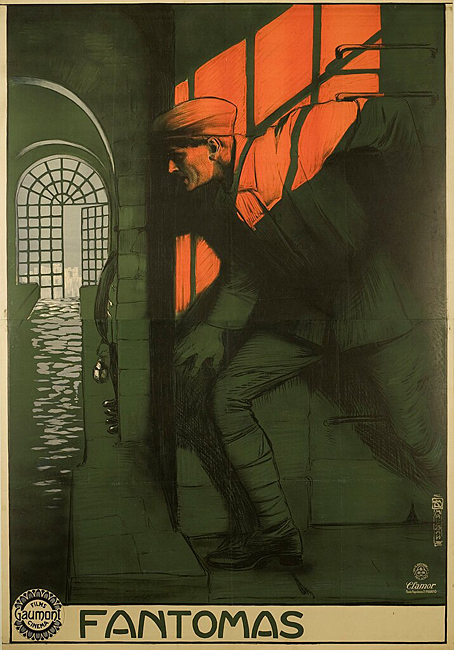

Uncredited poster art, 1913. The blood-stained dagger on the cover of the novel was too much for Gaumont.

This isn’t the first time I’ve written about Fantômas, the master criminal whose exploits thrilled French readers in the years before the First World War. But I’m writing now having finally read a translation of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre’s first Fantômas novel, and also watched the five Louis Feuillade films which introduced Fantômas to an international audience in 1913 and 1914. The novel was worth reading even though it doesn’t rise much above the pulp fiction of the time; Allain and Souvestre were writing in haste, their books were never going to win any literary awards. Fiction doesn’t have to be finely-crafted in order to capture the popular imagination (look at James Bond…), but Fantômas is unusual for being so popular while also being essentially formless: a persistently elusive criminal mastermind with no substantiated identity that the police can discover, whose prowess with disguise enables him to infiltrate French society at all levels. Criminal masterminds are plentiful in English literature but they’re usually hiding in the background of stories with heroes as the central character, as with Professor Moriarty and Sherlock Holmes. Guy Boothby’s Doctor Nikola has Fantômas-like qualities but he’s a more ambivalent character, less of an outright villain. A closer English comparison might be Fu Manchu whose first appearance in print was in 1912, a year after the literary debut of Fantômas. The rivalry between Fu Manchu and Denis Nayland Smith of Scotland Yard matches the tireless pursuit of Fantômas by Inspector Juve of the Sûreté; yet Fu Manchu still has a personal history and, in the later novels, motivations beyond mere criminality. Nothing is known of Fantômas outside his criminal endeavours. His character is so nebulous that one of the later stories sees Inspector Juve arrested after his superiors have convinced themselves that he must be the real hand behind the Fantômas crimes.

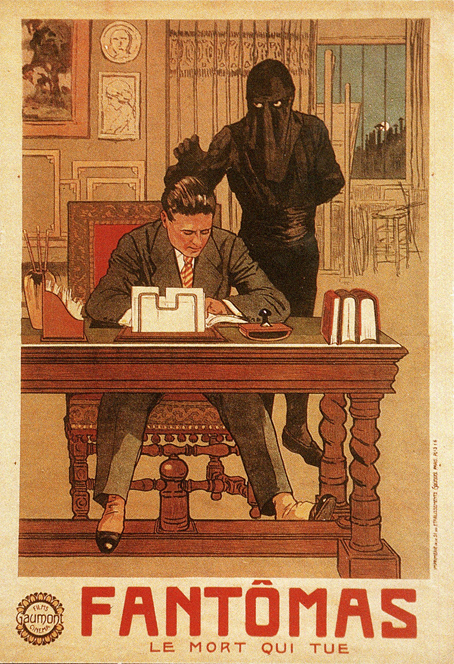

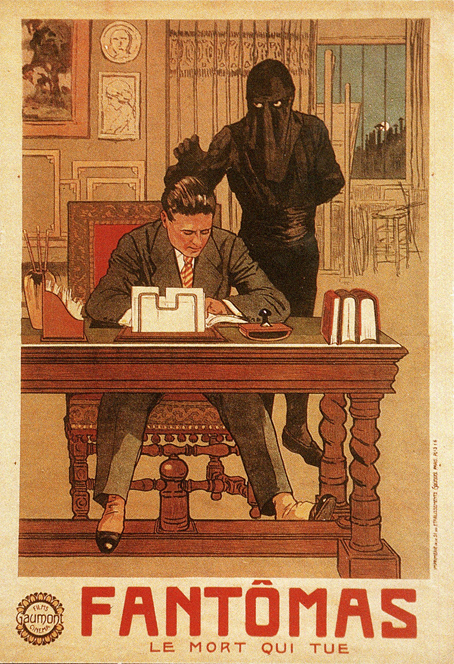

Uncredited poster art, 1913. Fantômas is about to turn his unwitting victim into “The Corpse that Kills”.

On an artistic level the Feuillade adaptations are much more satisfying than their source, even though Fantômas in the films isn’t as triumphantly murderous as he is in the books. After years of only knowing the adaptations from blurred and washed-out stills it’s been a revelation to see the recent Gaumont restorations which have been mastered from the best available prints, cleaned of scratches and other flaws, and projected at the proper speed. The Feuillade serials have circulated for years in inferior copies but I’d always held off watching them in the hopes that better prints might arrive. I’m glad I waited. Cinema was still a young medium in 1913 but Feuillade was a good director, skilled at creating suspense and engineering sudden surprises. He was also working with a decent troupe of actors, especially René Navarre as the villainous leading man. The misconception that early silent acting is all grandiose gestures and exaggerated facial expressions is dispelled in films like these where the acting is generally restrained even when the subject matter is lurid and melodramatic.

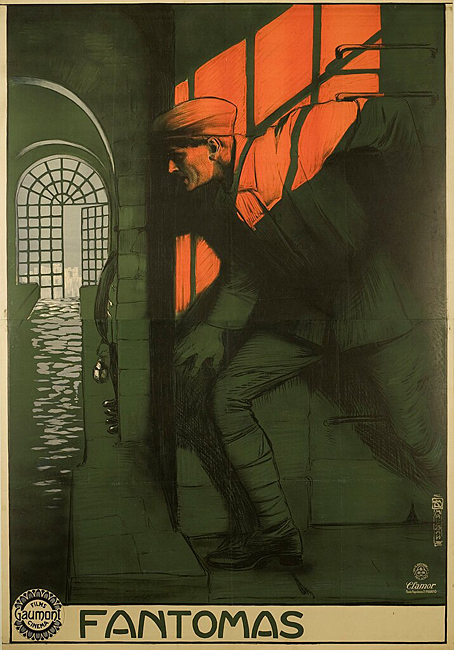

Poster art by Achille Mauzan, 1913.

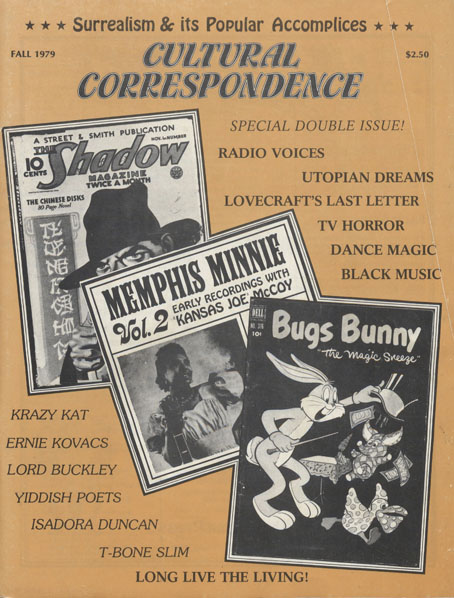

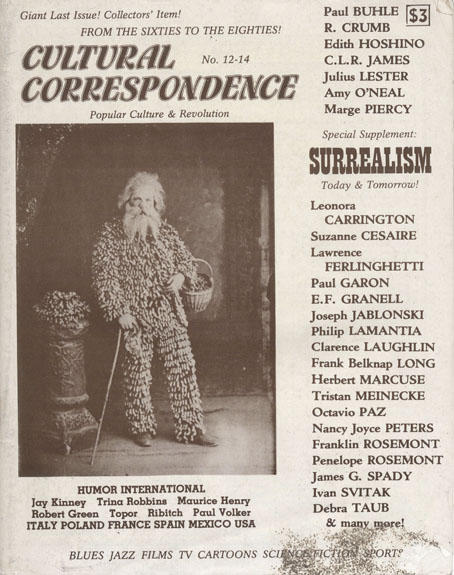

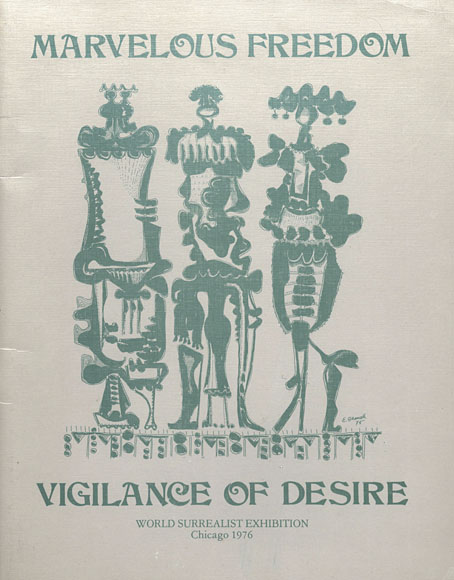

The UK release of the Feuillade films by Eureka happens to arrive just after 100th anniversary of the first Surrealist Manifesto, a coincidence, no doubt, but a fitting one. The Surrealists enjoyed the “waking dream” quality of the cinema experience, and were especially besotted with Feuillade’s Fantômas serials:

Over the next two decades, Fantômas was championed by the Parisian avant-garde, first by the young poets gathered around Guillaume Apollinaire, who, together with Max Jacob, founded a Société des Amis de Fantômas in 1913, and later by the Surrealists. In July 1914, in the literary review Mercure de France, Apollinaire declared the imaginary richness of Fantômas unparalleled. The same month, in Apollinaire’s own review, Les Soirees de Paris, Maurice Raynal proclaimed Feuillade’s Fantômas saturated with genius. Over the next two decades, poets such as Blaise Cendrars (who called the series “The Aeneid of Modern Times”), Max Jacob, Jean Cocteau, and Robert Desnos, and painters such as Juan Gris, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte, incorporated Fantômas motifs into their works. Pierre Prévert’s 1928 film, Paris la Belle, featured a Fantômas book cover in the closing sequence, and the Lord of Terror was adapted to the Surrealist screen in Ernest Moerman’s 1936 film short, Mr. Fantômas, Chapitre 280,000. As the century progressed, Fantômas remained a minor source of artistic inspiration as the subject of cultural nostalgia.

Robin Walz from Serial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and the Mass-Culture Genealogy of Surrealism (1996)

All of which has had me searching for examples of the above, some of which I hadn’t seen before. Fantômas was a recurrent source of inspiration for René Magritte yet “the Lord of Terror” is often reduced to a footnote in discussions of Magritte’s career. The appropriation of the name of Fantômas, along with motifs from the novels and films, is a unique moment in art history, one that points the way to the further appropriations of Pop Art and the cultural free-for-all we see in the art world today.

Continue reading “Enfantômastic!”