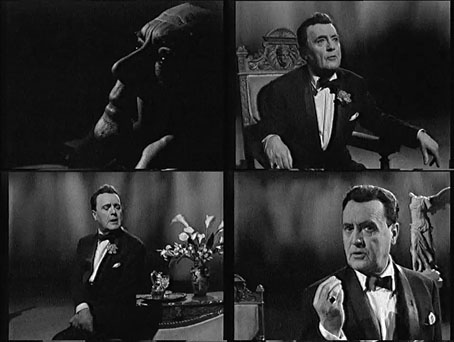

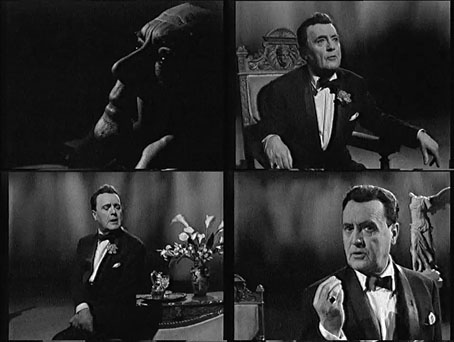

Picking up where we left off, I was thrilled to find that Micheál MacLiammóir’s one-man dramatised biography of Oscar Wilde had finally made it to YouTube. The Importance of Being Oscar was MacLiammóir’s 100-minute magnum opus, an acclaimed condensation of Wilde’s life and work first performed at the Gate Theatre, Dublin, in 1960. Hilton Edwards produced for partner MacLiammóir who subsequently took his show around the world, including performances on Broadway.

MacLiammóir’s monologue interleaves sketches of Wilde’s life with substantial extracts from the major works—An Ideal Husband, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Importance of Being Earnest, De Profundis, and The Ballad of Reading Gaol—with the actor/writer often taking two roles in the same scene. The readings are deeply felt; this would have been a very personal project, not only for its subject being a fellow Irishman and playwright but also for MacLiammóir and Edwards’ status as gay men in Ireland at a time when they could never be open about their private lives. (Or openly secretive: Barbara Leaming’s biography of Orson Welles makes it clear that iniquitous laws did nothing to stifle the pair in their pursuit of other men.) Accounts of Wilde’s post-trial life are inevitably sombre but MacLiammóir notes that even prison couldn’t suppress Wilde’s sense of humour. A literary conversation with one of the warders is recounted, along with the famous barb thrown at Marie Corelli: “Now don’t think I’ve anything against her moral character, but from the way she writes she ought to be in here.” If MacLiammóir’s performance seems a little overwrought in the television studio it would have appeared less so on the stage.

The BBC filmed The Importance of Being Oscar in the mid-60s, and I think that recording may be the one linked here, a version I recall being shown during an evening of Wilde-related TV in the late 1980s. Prior to this MacLiammóir had played Wilde himself for a televised dramatisation of the courtroom appearances broadcast by the BBC in 1960. This was a key year for reappraisals of Wilde’s reputation which also saw the cinema release of Oscar Wilde (with Robert Morley) and The Trials of Oscar Wilde (with Peter Finch). The latter is the superior film and performance even if Finch looks nothing like Wilde. Public attitudes were changing but all the films and TV plays at this time remained evasive about the precise nature of Wilde’s infractions. The Importance of Being Oscar follows this pattern with a fade to black after Wilde’s arrest; the second act opens with MacLiammóir as the judge passing sentence on Wilde and procurer Alfred Taylor. Circumspection doesn’t detract from the power of the monologue which has been revived in recent years, most notably by Simon Callow, another great Wilde enthusiast and also the biographer of MacLiammóir’s young protégé, Orson Welles.

Now that MacLiammóir’s monologue has resurfaced I’ll be hoping someone uploads John Hawkesworth’s Oscar (1985), a three-part television biography with Michael Gambon playing Wilde.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive