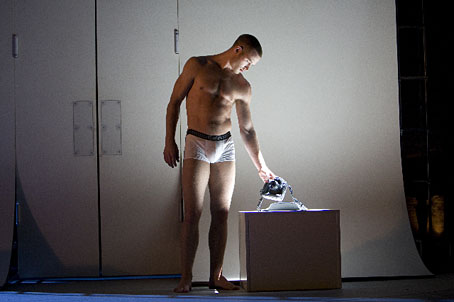

Dorian (Richard Winsor) photographed by Bill Cooper.

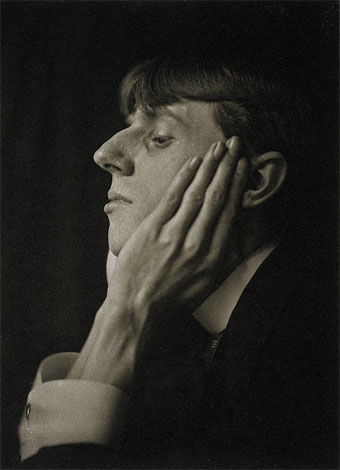

Matthew Bourne‘s new dance version of Dorian Gray opens today at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London, and I’d have been interested in this production even without visions like the ones above and below; the eye candy merely adds an additional frisson and, let’s face it, there’s always been an erotic component to dance and ballet however high-minded the intention. Bourne famously gave the world the a Swan Lake with male swans and in Dorian Gray updates Wilde in a very contemporary manner (following Will Self’s Dorian: An Imitation and Duncan Roy’s recent film adaptation) with the gay subtext made an overt text.

Set in the image-obsessed world of contemporary art and politics, Matthew Bourne’s ‘black fairy tale’ tells the story of an exceptionally alluring young man who makes a pact with the devil. Amongst London’s beautiful people, Dorian Gray is the ‘It Boy’ – an icon of beauty and truth in an increasingly ugly world.

The destructive power of beauty, the blind pursuit of pleasure and the darkness and corruption that lie beneath the charming façade; the themes behind Oscar Wilde’s cautionary tale have never been more timely.

Richard Winsor again, photographed by Murdo Macleod.

Dorian Gray continues the gender-reversals with Lord Henry becoming Lady H, while Sybil Vane is transmuted to Cyril. I like the stage design detail where the customary nightclub glitterball becomes a version of Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted human skull, the expensive artworld bauble finding its own level at last as a piece of decoration. Updating stories in this way often provokes a feeling of ambivalence—removing the subtext can have the effect of diluting the tension which lies at the heart of the work—but the continual refashioning of Wilde’s fable has confirmed its status as a contemporary myth, something I’m sure he’d be very pleased about. In that respect, it gives the creator the immortality through art which his creation, in the closing pages of the story, is denied.

• Because Wilde’s worth it | Matthew Bourne discusses the production

• Review in The Independent

• Bill Cooper’s production photos

• Wilde at heart: Matthew Bourne’s Dorian Gray | Another photo gallery

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive