Regular readers may have noticed that Jiří Trnka’s name has been written here with all the Czech accents intact, something that hadn’t been possible until a few days ago thanks to a database coding fault. This had long been the case with accents like those used in Czech, Polish, Turkish, Japanese, and other languages, to my endless frustration. I’ll spare you the technical details but the solution, which I resolved at the weekend, turned out to be easier than I expected, as a result of which I’ve been going back through posts adding accents to names which until now had been incomplete.

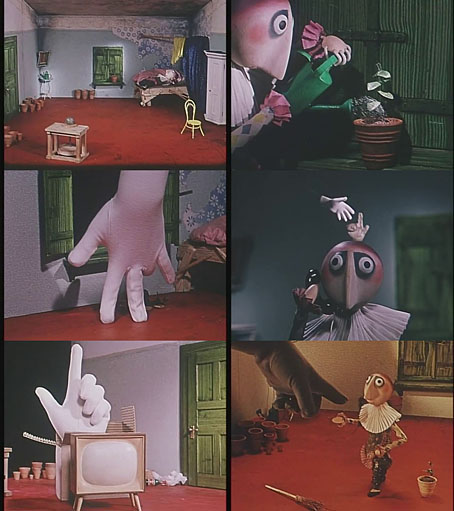

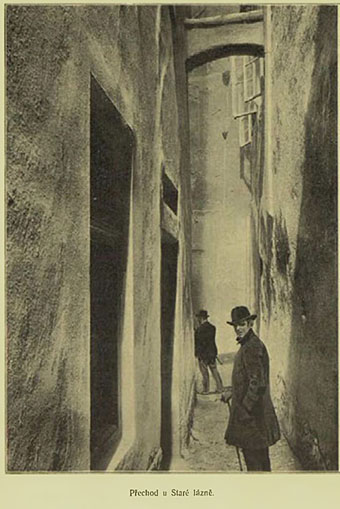

Jiří Trnka (1912–1969) came to mind while I was restoring the accents for Jiří Barta; both men are Czech animators, with Barta having been mentioned here on many occasions. Trnka was one of the founders of the Czech animation industry whose puppet films aren’t always to my taste but I thought I might have mentioned The Hand (1965) before now. This was Trnka’s final film, and one of his most celebrated for its wordless presentation of a universal theme: the freedom of the artist in the face of authoritarian demands. Many of Trnka’s previous films had been stop-motion puppet adaptations of fairy tales which lends The Hand a subversive quality when the scenario seems at first to be pitched in a similar direction. The artist character is a typical Trnka puppet with a persistently smiling face who spends his time in a single room making flowerpots with a potter’s wheel. “The hand” in this context refers both to the manual nature of the potter’s craft as well as to the huge gloved appendage that forces its way into the room demanding that the pots be abandoned in favour of hand-shaped sculptures. The resulting battle of wills shows the strengths of animation in delivering a potent visual metaphor.

Trnka’s message at the time of the film’s release was especially pertinent for the Soviet satellite nations where the promise of post-war Communism had been corrupted by decades of repressive governments, a situation that Jan Švankmajer bitterly addressed in The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia. Trnka isn’t as savage as Švankmajer but his message is still an ironic one, and may have been fuelled by an equivalent bitterness. Trnka’s career was bookended by films showing the struggle of assertive individuals against authoritarian oppression, but in the first of these, The Springman and the SS (1946), the contest is between a Czech chimney-sweep and the Nazi occupiers. The Hand could only be taken by Czech viewers as being aimed at their own oppressive government, and as such may be seen as Trnka’s contribution to the Czech New Wave, especially those films (Daisies, The Cremator) that the same government regarded as politically subversive or otherwise harmful. The Hand, like The Cremator, was withdrawn from distribution a few years after its release. Jiří Barta is a very different director to Trnka but Barta’s The Vanished World of Gloves (1982) features a dystopian sequence showing a fascist world of marching hands which looks like a homage to Trnka’s film. Watch The Hand here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jiří Barta: Labyrinth of Darkness

• Jiří Barta’s Pied Piper