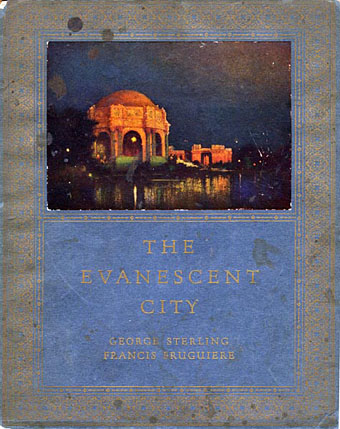

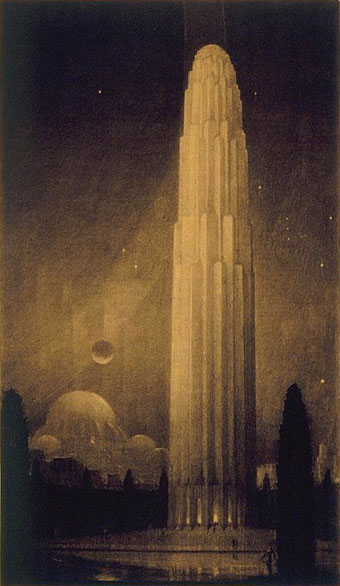

The cover of The Evanescent City shows a night view of Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts, one of the few remaining structures from the Panama-Pacific International Exposition that was held in San Francisco in 1915. After earlier posts about ephemeral architecture and the futuristic visions of Hugh Ferriss, I stumbled across the Books about California site which features a wealth of scanned volumes, including a number of books and pamphlets devoted to the Panama-Pacific Exposition. Expositions and World’s Fairs hold a particular attraction for enthusiasts of architectural invention, not least for the way they allow architects the opportunity to create structures that would otherwise never be built.

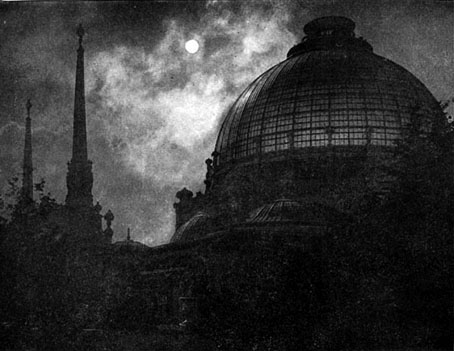

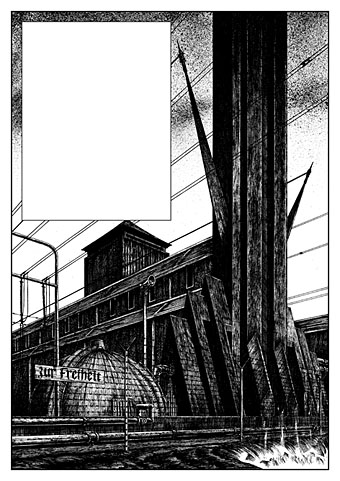

Palace of Horticulture—Dome and Spires by Night from The Architecture and Landscape Gardening of the Exposition.

At night, when the powerful searchlights within the dome are played upon the translucent glass, the effect is magical, the reflections weirdly changing in color and shape. The rich details of the decorations are softened in the night light.

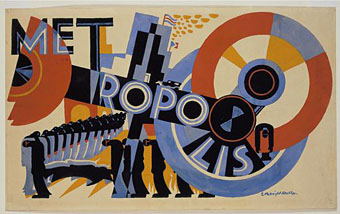

The Panama-Pacific Exposition and the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago fascinate owing to the insight they give into the 19th- and early-20th century architectural imagination. This invariably meant huge towers, enormous domes and everything ladled with elaborate decoration, the Panama-Pacific Exposition being especially decadent in this respect, numbering a jewel-spangled tower among its attractions. With the Bauhaus innovations a few years away this was the last time the world would be offered a reflection of itself that was so excessively indebted to the past. If Hugh Ferriss shows us a vision of the world like that in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the Panama-Pacific architects invite us to imagine a world like the Slumberland that Winsor McCay created for Little Nemo.

The Internet Archive has a number of short films showing views of the exposition. Most interesting, if rather crudely made, is The Story of the Jewel City, a brief fantasy about two children exploring the exposition grounds.

The following pictures are a small sample of the amount of material at Books about California. The snake-entwined figure of Helios would have made a good addition to the Men with snakes post while it’s difficult not to smile at the suggestion that the figure of a naked man should be preserved for America’s future gay capital.

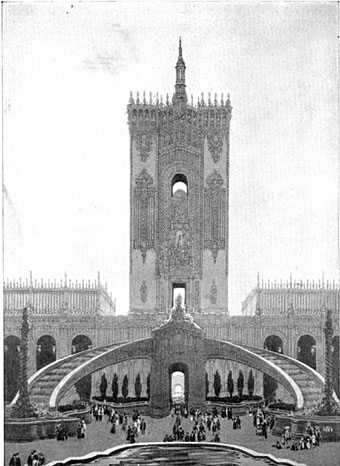

Tower of Jewels—the Illumination by Night from The Architecture and Landscape Gardening of the Exposition.

The Tower takes its name from the thousands of many-colored jewels so cut, polished and suspended that they reflect the sunshine with dazzling brilliancy by day and at night, under the white radiance of the searchlights, clothe the whole structure with shimmering splendor.

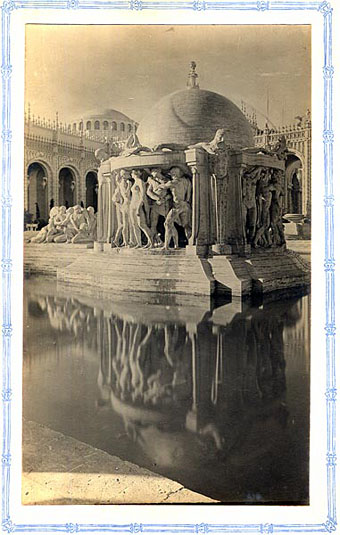

The Fountain of Earth from The Court of Ages by Beatrice Wright.

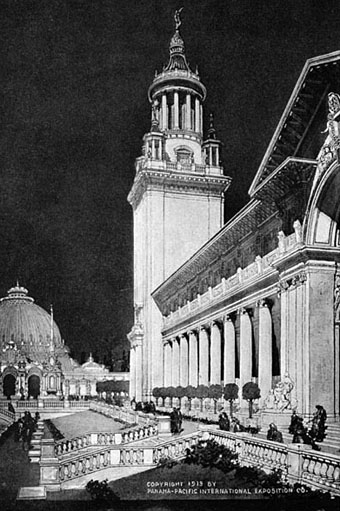

Part of Education Building and Court of Palms looking towards Horticultural Building from Panama-Pacific International Exposition—Popular Information.

Tower and Cascade in Court of Abundance from the Official View Book of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

Dedicated to Music and Pageantry. Water in the cascade flows over a scheme of brilliant illumination. Designed by Louis Christian Mullgardt.

Palace of Horticulture—The Dome and East Entrance from The Architecture and Landscape Gardening of the Exposition.

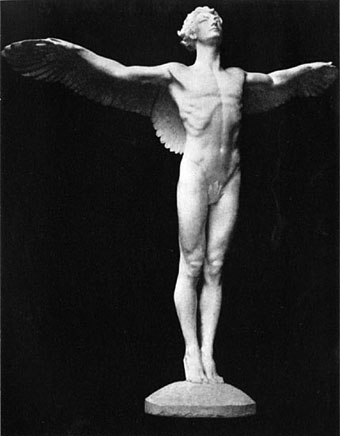

Helios by Robert I Aitken from The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition.

The Rising Sun by Adolph Alexander Weinman from Sculpture of the Exposition Palaces and Courts by Juliet Helena Lumbard James.

This fresh, strong young Sun is about to start on his journey – dawn is soon to break upon the world. With muscles stretched, the wind blowing through his hair, the heavenly joy of the first move expressed upon his face, the vigor of young life pulsating through his body, he will start the chest forward and move those outstretched wings. Let us preserve this glorious figure for our western city. It would so admirably suggest the new light that has been shed upon San Francisco by the Exposition of nineteen hundred and fifteen, as well as the new light occasioned by the opening of the Panama Canal.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ephemeral architecture

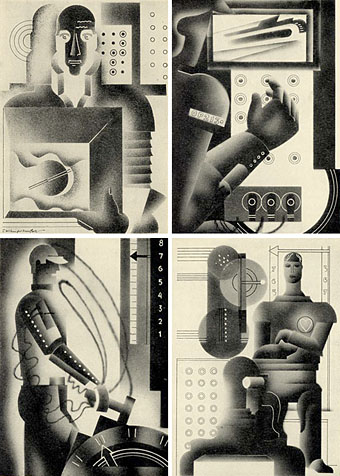

• Hugh Ferriss and The Metropolis of Tomorrow

• Winsor McCay’s Hippodrome souvenirs

• The World in 2030

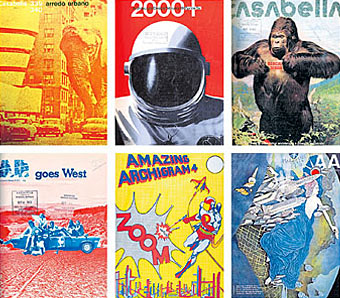

• Metropolis posters

• Frank Lloyd Wright’s future city