The Book of Hyperborea (1996). Cover art by Robert H. Knox.

“My Hyperborean tales, it seems to me, with their primordial, prehuman and sometimes premundane background and figures, are the closest to the Cthulhu Mythos, but most of them are written in a vein of grotesque humor that differentiates them vastly.” — Clark Ashton Smith

Since re-reading Clark Ashton Smith’s The Tale of Satampra Zeiros I’ve been revisiting more of Smith’s stories set in the lost world of Hyperborea. And having put together a post some years ago that gathered all the original illustrations for Smith’s Zothique cycle, I thought I’d try and do the same for another of his story series. As I noted in the earlier post, we’re fortunate today that it’s so easy to see illustrations that in the past would have been impossible to find unless you owned (or had access to) a huge collection of pulp magazines. Pulp illustrations aren’t always very good—in the case of the early issues of Weird Tales, they’re frequently amateurish—but those that illustrate new fiction for the first time are historically important if nothing else.

Lost Worlds: Volume 1 (1974). Cover art by Bruce Pennington. Lost Worlds was a single-volume collection published by Arkham House (USA) and Neville Spearman (UK). The Panther paperback covers by Bruce Pennington could easily be used on other books but these were the first Smith volumes I owned.

The first Hyperborea stories were among Smith’s earliest prose fantasies, owing something to Lord Dunsany on the one hand (HP Lovecraft detected a Dunsanian quality), and the writers of antiquity on the other, the name “Hyperborea” (“Behind the North Wind”) being borrowed from the Greeks. The northern location is about the only feature of the continent that the Greek writers would recognise, Smith’s world being a temperate pre-Ice Age realm of mountains and verdant jungles. Dinosaurs and megafauna share the lands with human inhabitants for whom sorcery is a common practice. As with Zothique, the cycle was an influential one. Lin Carter in the introduction to his Ballantine collection, Hyperborea (1971), suggests that the name of the continent might have prompted Robert E. Howard to set his Conan stories in “the Hyborean Age”. This could be the case: Howard and Smith were writing for the same publications, and the first Conan story was published in Weird Tales shortly after The Tale of Satampra Zeiros; but Howard was also reading the Greeks as well. A more substantial influence may be found in Fritz Leiber’s Nehwon, a world in which aspects of Hyperborea and Zothique are combined. Sword and sorcery begins “behind the North Wind”, in other words, although there’s very little sword-play in Smith’s fiction, that was Leiber and Howard’s department.

Lost Worlds: Volume 2 (1974). Cover art by Bruce Pennington.

The original Hyperborea illustrations are fewer than those for Zothique. As with the later cycle, several of the stories are unillustrated, while others were given lacklustre artwork. In the earlier post I followed the story order chosen by Lin Carter which attempted to contrive an internal chronology for the cycle. Carter did the same with his Hyperborea collection so I’ve followed his example once again. Later collections, like Will Murray’s Book of Hyperborea, tend to order the stories by publication date.

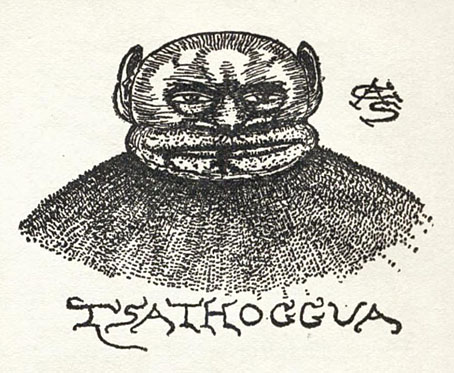

The Seven Geases, Weird Tales, October 1934.

An illustration of Tsathoggua by Smith himself. The toad-god turns up in person in this story.

The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan, Weird Tales, June 1932.