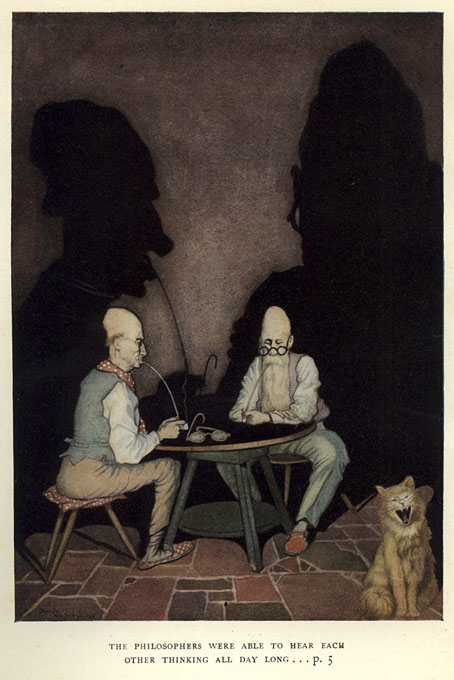

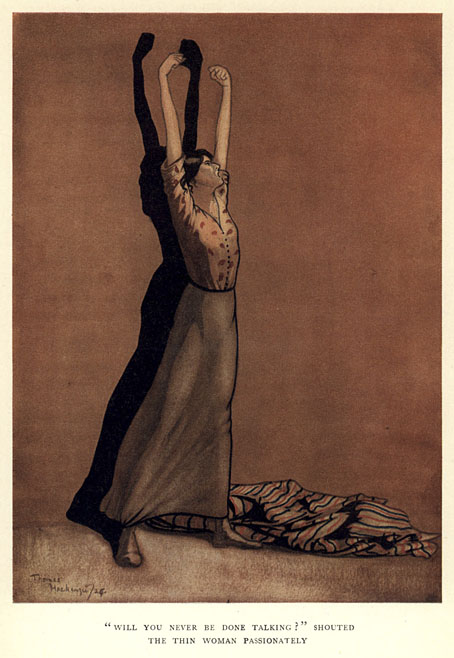

The fin-de-siècle interest in Japanese art is given a twist by four small books in which a group of Japanese artists illustrate well-known fables for a French readership. The books were commissioned circa 1890 by Pierre Barboutau, an art collector who specialised in Japanese arts and crafts. Barboutau’s volumes would have been intended to broaden the interest in Japanese art which had been fuelled a few years before by Le Japon Artistique, a magazine edited by a German art dealer with a business in Paris, Siegfried Bing. Le Japon Artistique was criticised for its inaccuracies by Japanese readers but it did feature colour reproductions of prints which otherwise might only be seen as monochrome reproductions. (Bing’s Paris shop, L’Art Nouveau, is also historically significant for giving a name to the predominant mode of fin-de-siècle design.)

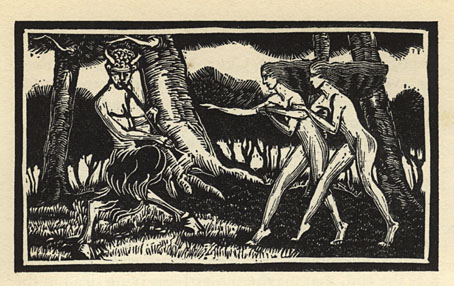

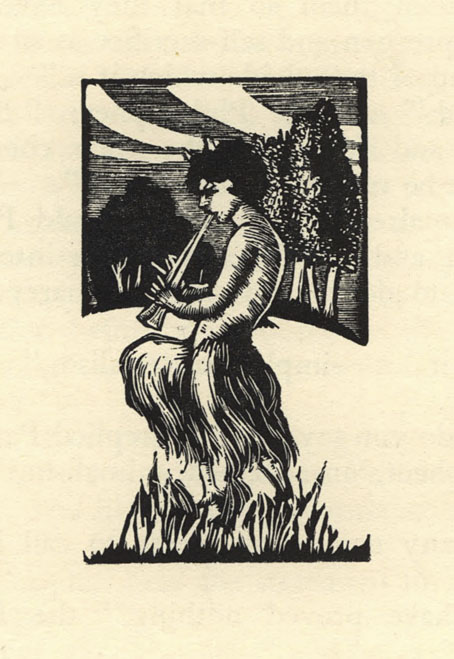

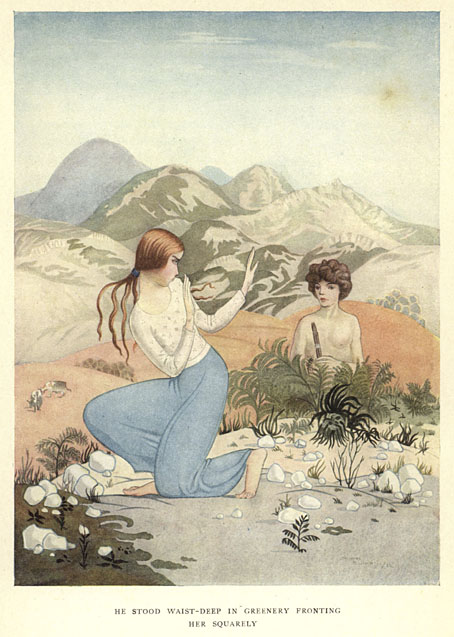

Barboutau’s books take the French interest in Japonisme a stage further, allowing readers to experience familiar stories through Japanese eyes. Each book was printed in a limited run on Japanese paper. Of the four, I’m only familiar with the fables of La Fontaine where the emphasis on animal characters in rural settings means there are few explicitly Japanese details. Some of the landscapes are more Japanese than French, however, especially the drawing that includes a Fuji-like mountain in the background. There’s also a drawing of a group of foxes where the background details of a shrine and torii gate seem intended more for Japanese readers. Foxes in Japan are associated with the Shinto deity, Inari, to a degree that fox statues are a common site in Shinto shrines. None of this is mentioned in the book but if you’re aware of the significance it adds an additional layer to the cultural intersections.

All these books may be seen at Gallica, a valuable site whose interface is still woefully bad, especially on mobile devices. My advice, as always, is to download the PDFs.

Choix de fables de La Fontaine, Tome 1 (1894)