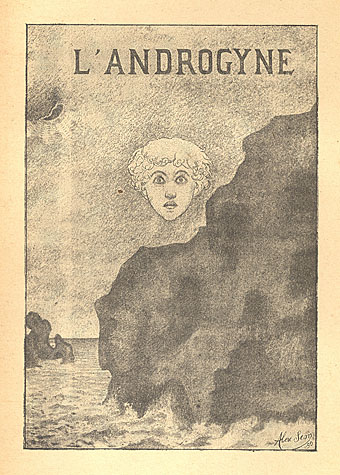

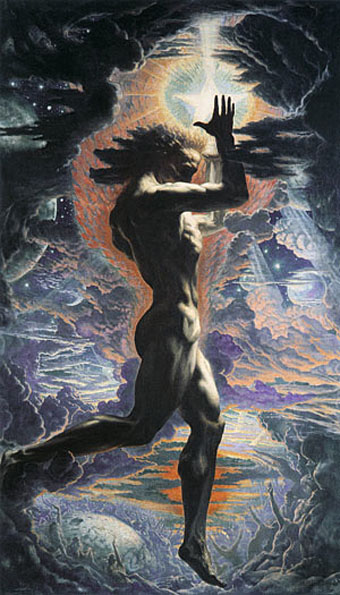

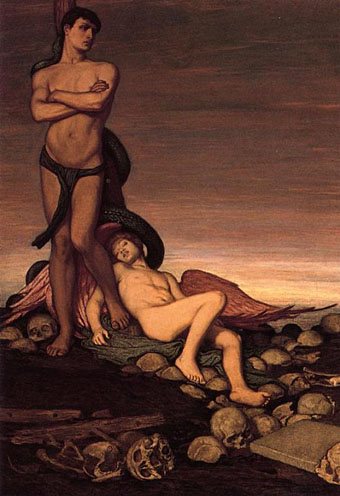

L’Androgyne by Alexandre Séon (1890).

Related to yesterday’s post, I’ve been re-reading various books this week for details of the most curious character associated with the French Symbolist movement, novelist and occultist Joséphin Péladan (1859–1918), also known as Sâr Peladan, a Babylonian title he bestowed upon himself as more befitting his adopted role as Rosicrucian mystic. Péladan’s writings and occult art theories spurred many of the painters who banded together as part of his Salon de la Rose+Croix, a kind of anti-salon intended to stand in opposition to what the Sâr saw as the drab realism of the Impressionists and the staid historicism of academic painters. One gets the impression reading about Péladan that he was probably a rather preposterous figure—his obsession with androgyny caused him to change his forename from Joseph to Joséphin yet he kept his length of bristling beard. But, like Oscar Wilde in London, his presence in the pool of fin de siècle art creates considerable ripples. Alexandre Séon, whose frontispiece above was created for Péladan’s semi-autobiographical essay, L’Androgyne, was particularly devoted to him, as was Carlos Schwabe. Séon’s picture depicts “the androgyne Samas, stupefied by the sexual enigma”, a character with whom Péladan fully identified as he describes his youth and its apparent state of androgynous grace.

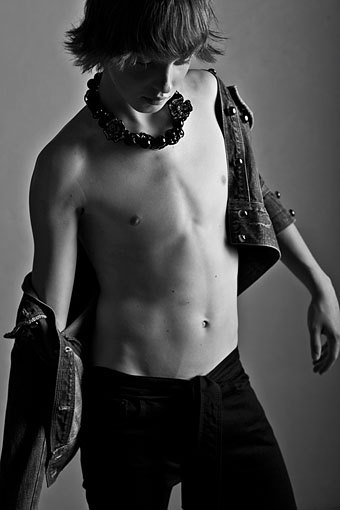

One doesn’t need a Rosicrucian salon today for examples of creative androgyny, of course, all you have to do is go to Flickr where you’ll find creatures such as the boy above from Roman Mitchenko’s photostream. The photos there are at the fashion end of the spectrum; for more of an amateur or semi-professional perspective there are groups like the Androgyny pool, and the Mommy, I want to be androgynous! pool, the latter featuring many striking boyish girls and girlish boys.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Arthur Tress’s Hermaphrodite

• Carlos Schwabe’s Fleurs du Mal

• Czanara’s Hermaphrodite Angel