Today is Outer Alliance Pride Day so let’s begin with a statement:

Today is Outer Alliance Pride Day so let’s begin with a statement:

As a member of the Outer Alliance, I advocate for queer speculative fiction and those who create, publish and support it, whatever their sexual orientation and gender identity. I make sure this is reflected in my actions and my work.

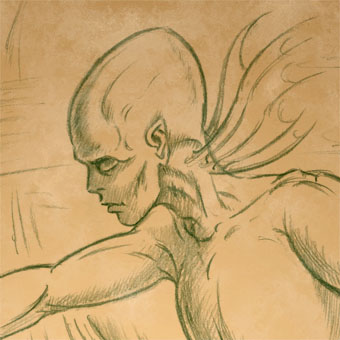

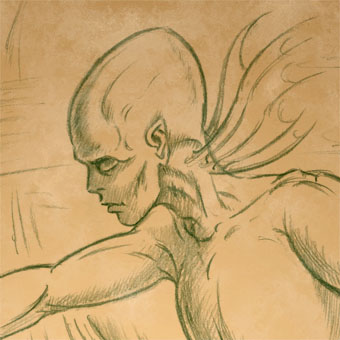

Various members of the Outer Alliance are either posting fiction, or reviewing something or otherwise attempting to fill that declaration of intent. For my part I decided today to do a sketch based on my favourite chapter of The Ticket that Exploded by William Burroughs, the sequence entitled the black fruit which Burroughs wrote with Michael Portman. Ticket was the first Burroughs book I read at the age of 16 or so, having discovered a copy in a local library, and it really felt like something exploding in the head. For a start, the text is some of his least accommodating for an average reader, although I was already familiar enough with literary experiment to cope with that. Far more electrifying was seeing familiar scenarios from science fiction and fantasy infused with a raw and relentless gay sexuality of endless erections and spurting cocks. The black fruit begins with a science fiction scene of lost astronauts encountering alien fishboys intent on having sex; it then progresses through a series of descriptions which read like a pornographic rewriting of similar scenes from HP Lovecraft or Clark Ashton Smith. In the opening pages of Ticket, Burroughs describes his book as “science fiction” but this was like no sf I’d read; I started to wish there was more like it. There are flashes of similar stuff in The Soft Machine (including an idea borrowed from Henry Kuttner) and elsewhere, and Cities of the Red Night is pretty much a full-on fantasy in its second half, but I’d still like to read more about the fishboys…

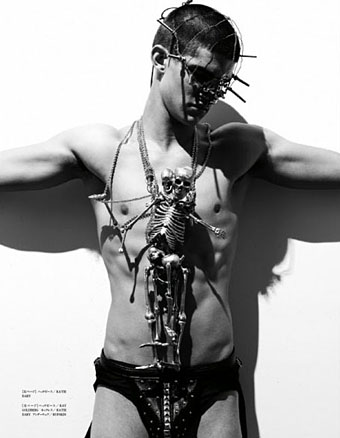

Fishboy and Astronaut (detail).

So here’s an explicitly erotic sketch based on the black fruit (click the picture for the full thing). This should have been a lot better but I’m out of practice drawing at the moment and I didn’t give myself enough time. The scene doesn’t really match the book either, and the astronaut figure is pretty crappy. Feeble excuses aside, Burroughs’ rotting swamp gardens with their marble statues of copulating boys deserve better. And where his fiction leads, I’m still hoping that more writers will follow, not by copying his obsessions but by being as fearless and honest in mining their own.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• William S Burroughs: A Man Within

• The art of NoBeast