Clouzot’s towering inferno | A film called Hell.

Category: {film}

Film

A playlist for Halloween: Voodoo!

It’s become a tradition here to post a playlist for Halloween so here’s the one for this year, a collection of favourite “voodoo” music. Most are these pieces have as much to do with real voodoo as Bewitched does with real witchcraft but I like the atmospheres of Voodoo Exotica they evoke.

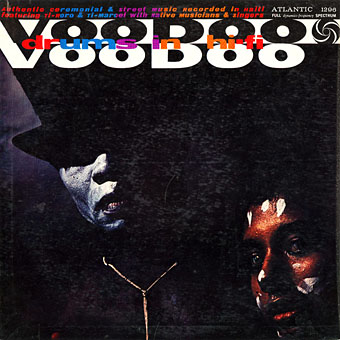

Voodoo Drums in Hi-Fi (1958).

Beginning with some ethnographic authenticity, this is one of many recordings of genuine (so they claim) voodoo drummers from Haiti, and was probably released to cash-in on the Exotica boom of the late Fifties. For the genuine article, the drums here sound less dramatic than the pounding rhythms familiar from Hollywood rituals, but that’s still a great cover. Voodoo Drums in Hi-Fi has been deleted for years but a worn copy of the vinyl release can be found on various mp3 blogs. For a more recent recording of voodoo rhythms, there’s Spirits Of Life: Haitian Vodou on the Soul Jazz label.

Voodoo Dreams (1959) by Martin Denny.

This, meanwhile, is the genuine kitsch from Denny’s Hypnotique album, a slow arrangement of a syrupy Les Baxter tune. More drums and bongos than usual for a Denny piece, and a suitably spectral chorus.

Voodoo (1959) by Robert Drasnin.

When composer Drasnin was asked by the Tops company to get hip to the Exotica craze the result was an album entitled Voodoo (with unconvincingly exotic white people on the cover), from which they released a single, Chant of the Moon, and this track as the B-side, one of the best pieces on the album.

I Walk on Gilded Splinters (1968) by Dr John.

Mac Rebennack was working as a session musician in Los Angeles when he recorded his debut album in an atmosphere far removed from the swampy New Orleans miasma which the music conjures. Gris-Gris owes a great deal to Robert Tallant’s book, Voodoo in New Orleans (1946), a popular recounting of the city’s occult legends from which Rebennack borrowed not only his new persona (chapter 5 concerns the history of the real Dr John, a 19th century voodoo practitioner) but also many of the transcribed chants which he set to music. In chapter 3 we read this:

A song given to a reporter of the New Orleans Times-Picayune was printed in that newspaper on March 16, 1924. Probably a very old one, it reflects the dominance of the queens in New Orleans Voodoo and boasts of their tremendous power. Originally sung in the patois known as Creole, it is given here in English:

They think they frighten me,

Those people must be crazy.

They don’t see their misfortune

Or else they must be drunk.I—the Voodoo Queen,

With my lovely headkerchief

Am not afraid of tomcat shrieks,

I drink serpent venom!I walk on pins

I walk on needles,

I walk on gilded splinters,

I want to see what they can do!They think they have pride

With their big malice,

But when they see a coffin

They’re as frightened as prairie birds.I’m going to put gris-gris

All over their front steps

And make them shake

Until they stutter!

Anyone familiar with Gris-Gris will recognise the lyrics of I Walk on Gilded Splinters (misspelled “Guilded” on the sleeve) which Dr John did a great job of fashioning into a classic voodoo song. The entire album might be ersatz, then, but it remains one of my favourites by anyone, and for me it’s still the best Dr John album.

Mama Loi, Papa Loi (1970) by Exuma.

Gris-Gris was too weird to be a success when it first appeared but Dr John’s music and extravagant stage presence were very distinctive and helped Blues Magoos manager Bob Wyld recast singer Tony McKay as “Obeah man” Exuma for Mercury Records. Exuma’s self-titled debut album is ersatz stuff again but manages to sound even more deliriously swampy and sorcerous than Gris-Gris, with jungle sounds, zombie gurgles and a clutch of enthusiastic voodoo-inflected songs. “Mama Loi, Papa Loi / I see fire in the dead man’s eye” he sings here, and for the duration of the album Tony McKay is Exuma.

Zu Zu Mamou (1971) by Dr. John.

After Gris-Gris Dr John gradually pared away the voodoo songs but saved one of the best until his final occult outing, The Sun, Moon & Herbs, which includes contributions from Eric Clapton and, somewhere in the bayou distance, Mick Jagger and PP Arnold on backing vocals. Zu Zu Mamou is the spooky highlight which made a fleeting appearance in Alan Parker’s 1987 Satanic noir, Angel Heart.

Voo Doo (1989) by the Neville Brothers.

Of all the songs I’ve heard which equate falling in love with a voodoo spell, this one from New Orleans’ Neville Brothers is the most evocative, a track from their marvellous Yellow Moon album.

Invocation To Papa Legba (1989) by Deborah Harry.

Yes, it’s Blondie’s Debbie Harry singing a very authentic-sounding voodoo chant, arranged by Chris Stein. This was a one-off which appeared on a Giorno Poetry Systems collection, Like A Girl, I Want You To Keep Coming, along with a William Burroughs reading (a staple of GPS albums), New Order playing Sister Ray live, and other pieces.

Litanie Des Saints (1992) by Dr. John.

Goin’ Back to New Orleans, like Gumbo before it, saw Dr John revisiting the musical history of his native city. Most of the songs are old jazz and blues covers with the notable exception of this opening number, another voodoo invocation. A great string arrangement and vocals from the Neville Brothers; I’d love to hear a whole album like this.

Zombie’ites (1993) by Transglobal Underground.

Zombies are a voodoo staple despite their current degraded status as the cuddly monster du jour, a development which has made me tire of seeing the word “zombie” in almost any context. A shame because I used to have a lot of time for films such as White Zombie (1932), I Walked With a Zombie (1943), and the later George Romero movies. White Zombie was the first zombie film and stars Bela Lugosi in a weirder and more effective piece of horror cinema than the stagey Dracula which made his name; I Walked With a Zombie was one of Val Lewton’s superb noirish collaborations with Jacques Tourneur; both films have their voodoo chants sampled on this track by Transglobal Underground from Dream of 100 Nations, with the opening chant from White Zombie forming the pulse that drives the piece. Along the way there’s another invocation from Voodoo in New Orleans—”L’Appé vini, le Grand Zombi / L’Appé vini, pou fe gris-gris!”—samples of Criswell from Plan 9 from Outer Space, and a moment of pure bliss at the midpoint when singer Natacha Atlas rides in on a magic carpet made of Bollywood strings.

Happy Halloween! And don’t forget to feed the loas…

• Vampire-hunting in New Orleans

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Voo-doo: Hoochie Coochie and the Creative Spirit

• Dead on the Dancefloor

• Another playlist for Halloween

• Exotica!

• White Noise: Electric Storms, Radiophonics and the Delian Mode

• The Séance at Hobs Lane

• Exuma: Obeah men and the voodoo groove

• A playlist for Halloween

• Ghost Box

• Voodoo Macbeth

Orson Welles: The most glorious film failure of them all

Orson Welles: The most glorious film failure of them all | David Thomson on why Welles still fascinates.

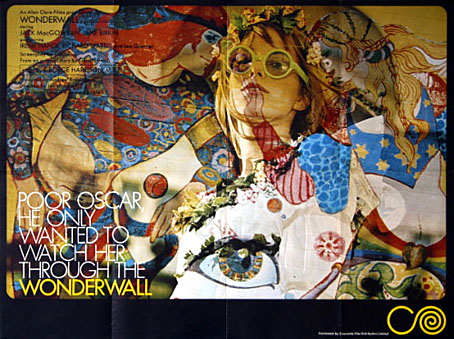

Through the Wonderwall

It’s taken me years but the recent obsession with UK psychedelia led me to finally watch Joe Massot’s piece of cinematic fluff from 1968, Wonderwall, a film distinguished primarily for its score by George Harrison (with Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton playing pseudonymously), and its title which was swiped years later by a bunch of Rutles-imitators from Manchester. The story is so slight it would have barely sustained an hour-long TV film: absent-minded scientist (Jack MacGowran) becomes intrigued by his glamorous neighbour (Jane Birkin playing “Penny Lane”; yeah, right…) and knocks holes in the walls of his flat in order to scrutinise her modelling, partying and frequent undressing. Unlike Blow Up (1966, and also featuring Jane Birkin) and the later Performance (1970), both of which attempted to accurately pin down some of the modish aspects of the period, this is a very kitsch piece. That wouldn’t be so bad if it was entertaining kitsch like, say, Smashing Time (1967), but Massott has to resort to scenes of limp comedy and some rather dull dream sequences in order to pad the thing out. Between the handful of actual dialogue scenes there’s a lot of gloating over Ms Birkin’s flesh which no doubt satisfied one half of the audience but by today’s standards is hardly thrilling. Iain Quarrier plays Penny’s duplicitous boyfriend (with a fake Liverpool accent) in his last screen role before he quit acting. Quarrier and MacGowran had appeared together in two of Roman Polanski’s British films, Cul-de-sac (1966) and Dance of the Vampires (1967). In the latter, MacGowran again plays an absent-minded scientist while Quarrier is cinema’s first (?) gay vampire.

An interjection from The Fool.

Of chief interest for me in Wonderwall was the decor and title card decorations by Dutch psychedelic collective, The Fool (who also appear in the party scene), famous for their earlier Beatles associations including the inner sleeve for Sgt Pepper and designs for the short-lived Apple Boutique in London’s Baker Street. I was also curious about the distinctive decor of MacGowran’s flat which contrasts with the psychedelia next door, all dark green walls embellished with Victorian murals and a Tennyson poem—very fittingly a piece called The Daydream—which circles the room.

The professor prepares to attack the wall.

This was particularly interesting in that it made another connection between the psychedelic era and Victorian arts movements, especially from the Aesthetic/Arts & Crafts end of things, but it wasn’t at all obvious whether the connection was an intentional part of the film’s production design or an accident of location and budgetary convenience. Aside from the old-fashioned appearance of MacGowran’s rooms there seemed no reason why his otherwise cultureless character would have any interest in decorating his living space in this way.

The street corner then…

…and now.

The building itself is equally distinctive and an exterior shot conveniently shows a street sign placing the location in Lansdowne House, a Victorian apartment block on the corner of Lansdowne Road and Ladbroke Road in the Notting Hill/Holland Park area of London.

Lansdowne House.

What did the building look like today, I wondered? Google Earth proves indispensable at times like this and it was easy to find, in a street which looks more cramped than it does in the film. The presence of a blue plaque on the wall proved intriguing, a sign that the place once had famous residents. Googling for that revealed this photo which was a real surprise: Lansdowne House at one time contained studios for artists who included Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, a gay couple and leading lights of London’s fin de siècle art scene (also friends of Oscar Wilde), and another artist, James Pryde, who with William Nicholson worked as The Beggarstaffs. So my suspicion about the Arts & Crafts decor was correct, which means that MacGowran’s flat may have been decorated that way originally and remained untouched since the 1890s. I haven’t seen Rhino’s special edition of Wonderwall which contained additional information about the making of the film, so have no idea whether the history of the building is mentioned there. If anyone does know, please leave a comment. For now I’m quite happy to have stumbled upon another minor link between two of my favourite art decades.

For more visuals, this page has a host of screen grabs from the film as well as some gif animations, all of which manage to make Wonderwall seem more interesting than it is when you’re watching it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Charles Ricketts’ Hero and Leander

• Images by Robert Altman

Short films by Sergei Parajanov

Hakob Hovnatanyan (1967).

I’ve been enthusing for years about the unique films of Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990), usually in vain since his work hasn’t always been easy to see and is (for now) poorly served by DVD. His two masterworks, Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1964) and The Colour of Pomegranates (1968), have both been issued on disc but in shoddy versions with prints that are scratched and desaturated, and the latter suffers from poor subtitling. Parajanov’s films make bold use of colour and a washed-out print does him no favours at all. In an ideal world the BFI or Criterion would give these films the attention they deserve.

Grumbles aside, Ubuweb comes up trumps again by posting three of Parajanov’s shorter works, none of which I’d seen before. These give some idea of his distinctive tableaux style, and his recurrent preoccupation with decorative details and close views of objects.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Disasters of War