Quantum Entanglement by Duda Lanna.

• An hour-long electronica mix (with the Düül rocking out at the end) by Chris Carter for Ninja Tune’s Solid Steel Radio Show.

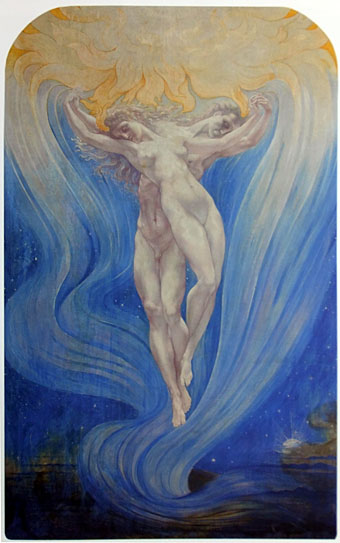

• “…a clothes-optional Rosicrucian jamboree.”: Strange Flowers on the paintings of Elisàr von Kupffer.

• A Paste review of volume 2 of The Graphic Canon has some favourable words for my contribution.

It is an entertaining thought to remember that Orlando, all sex-change, cross-dressing and transgressive desire, appeared in the same year as Radclyffe Hall’s sapphic romance The Well of Loneliness. The two novels are different solar systems. The Well is gloomy, beaten, defensive, where women who love women have only suffering and misunderstanding in their lonely lives. The theme is as depressing as the writing, which is terrible. Orlando is a joyful and passionate declaration of love as life, regardless of gender. The Well was banned and declared obscene. Orlando became a bestseller.

Jeanette Winterson on Virginia Woolf’s androgynous fantasia.

• Jim Jupp discovers the mystical novels of Charles Williams.

• Michael Andre-Driussi on The Politics of Roadside Picnic.

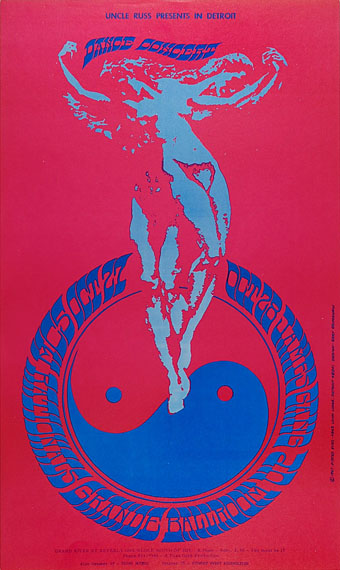

• Les Softs Machines: 25 August 1968, Ce Soir On Danse.

• At 50 Watts: Illustrations and comics by Pierre Ferrero.

• Soviet posters: 1469 examples at Flickr.

• Oliver Sacks on drugs (again).

• At Pinterest: Altered States.

• Farewell, Kevin Ayers.

• Why Are We Sleeping? (1969) by The Soft Machine | Lady Rachel (1969) by Kevin Ayers | Decadence (1973) by Kevin Ayers