Posters by Swedish artist Wilhelm Kåge (1889–1960) at the National Library of Sweden. Kåge is better known for his later ceramic work, some of which can be seen here.

Via @assemblyman_eph.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Einar Nerman

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Art

Posters by Swedish artist Wilhelm Kåge (1889–1960) at the National Library of Sweden. Kåge is better known for his later ceramic work, some of which can be seen here.

Via @assemblyman_eph.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Einar Nerman

Between heaven and hell.

These intaglio prints by Ukranian artist Oleg Denysenko remind me of Ian Miller in their fine, spidery detail, and Ernst Fuchs in some of their subject matter. Denysenko also makes sculptures based on some of his etchings.

Hermaphroditus.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The etching and engraving archive

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Ian Miller

• The art of Ernst Fuchs

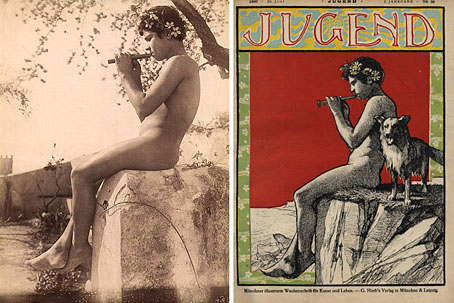

left: Sicilian boy by Wilhelm von Gloeden (no date); right: Jugend cover by Hans Christiansen (1896).

My current reading is The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2003), a long and fascinating study by Neil McKenna which attempts to disentangle the true nature of Wilde’s sex life from the myths and evasions of his biography and biographers. Among the pictures in the book, McKenna shows a couple of the “Uranian” photographs by Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856–1931) which Wilde owned. Von Gloeden’s views of naked Sicilian boys were described as “Classical” in a barely-believable subterfuge familiar during the 19th century, and it’s understandable why Wilde, who’d been praising the attractions of Mediterranean youth for most of his adult life, would have found these pictures worthy of purchase. Wikimedia Commons has a substantial set of the photos, although it should be noted that provenance is often uncertain; there were other photographers active in Taormina at the time who catered to a similar market. One photo in particular stood out recently when I recognised it as the possible source for the figure on a Hans Christiansen cover for Jugend magazine of 1896. The cover above has appeared here before but this is the first time I made the photographic connection.

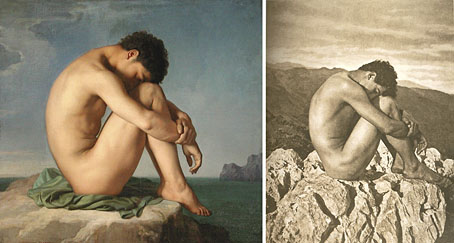

left: Jeune homme assis au bord de la mer by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1836); right: Cain by Wilhelm von Gloeden (c. 1902).

Gloeden, of course, was one of the first people to use the Flandrin pose, as I noted in the original post on that theme. I wonder if he knew he’d been copied in turn? That Jugend cover and its inspiration reminds me a little of Flandrin’s other depiction of Classical youth, his portrait of Polites, a painting which Oscar would no doubt have enjoyed.

Polites, Son of Priam, Observes the Movements of the Greeks by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1834).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The recurrent pose archive

• The Oscar Wilde archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Forbidden Colours

• Jugend Magazine

• Evolution of an icon

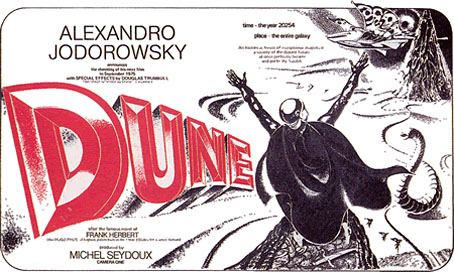

Fortunate Londoners can get to see a new exhibition, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ‘Dune’: An exhibition of a film of a book that never was, which runs at The Drawing Room until October 25, 2009. As well as production designs from concept artists Moebius, HR Giger and Chris Foss, there’s newly commissioned work by artists Steven Claydon, Matthew Day Jackson and Vidya Gastaldon.

Jodorowsky’s proposed 1976 adaptation of the Frank Herbert novel is now the stuff of legend, and it’s possible that his outrageously ambitious plans are more fun to dream about than they would have been on the screen. But it remains a tantalising prospect that Jodorowsky might well have pulled off a science fiction equivalent of Fellini’s Satyricon. Either way, along with Stanley Kubrick’s unmade Napoleon, it’s one of the great lost films of the 1970s.

Among Jodorowsky’s proposed cast were Orson Welles, Mick Jagger and Salvador Dali, the last of whom was to play the Emperor of the Universe, who ruled from a golden toilet-cum-throne in the shape of two intertwined dolphins. Unable to secure the money from Hollywood to create the ‘Dune’ of his imagination, Jodorowsky abandoned the film before a single frame was shot. All that survives of this project is Jodorowsky’s extensive notes, and the production drawings of Moebius, Giger and Foss. These reveal a potential future for sci-fi movie making that eschewed the conservative, technology-based approach of American filmmakers in favour of something closer to a metaphysical fever-dream.

left: Emperor Shaddam IV; right: Feyd Rautha.

Moebius’s designs are wildly different from those used in David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation (which I like nonetheless). His sketch of the Emperor on the left gives some idea of how Salvador Dalí might have appeared in the film, while the figure on the right is Baron Harkonnen’s effete nephew, Feyd, a far more radical conception than the grinning fool played by Sting in the Lynch version. There’s a lot more of Moebius’s sketches at the excellent Dune.info site.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dalí and Film

• Jodorowsky on DVD

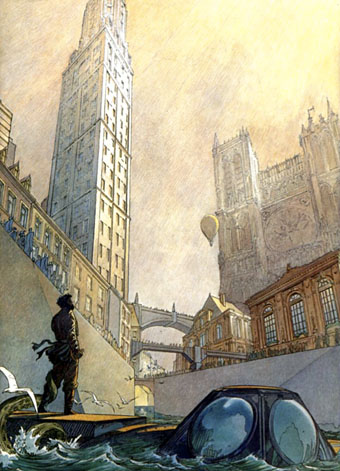

Mysterieux retour du Capitaine Nemo.

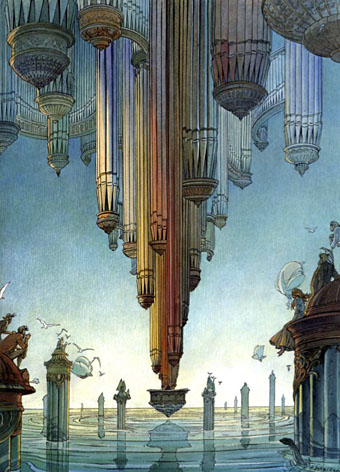

This week has been incredibly hectic work-wise but I’ve managed to keep these posts going, so here’s the last one devoted to an appreciation of the Cités Obscures of François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters. A week of posts barely scratches the surface of their vast and involved creation of alternate worlds, fantasy design and architecture, and Borges-like metaphysical speculation. When I try to explain my disaffection with the popular end of American comics, it’s works such as these which I offer as an alternative. The problem, of course, is that only a handful of the books have been translated into English, a detail which tells you all you need to know about English-speaking comics publishers and—since demand fuels the market—their readers.

This final set of pictures is a selection from Schuiten and Peeters’ L’Echo des Cités (1993), a facsimile edition of the main newspaper which serves the cities of the Obscure World. Unfortunately, this remains untranslated but the bulk of the book is full-page illustrations, many of which are among Schuiten’s best. A number of these were later reprinted as limited lithograph prints.

Les rêves engloutis d’Oscar Frobelius.