Here at last is something I’ve been waiting many years to see. Vampira is a strange German TV film which shouldn’t be confused with the horror comedy from 1974 that shares its name. Descriptions of the German Vampira make it sound like a drama-documentary but it’s really a kind of illustrated lecture with vampires as the predominant theme. George Moorse directed for the WDR TV channel which broadcast the film in 1971. Vampira is almost solely of interest today for the soundtrack by Tangerine Dream, a unique collection of short pieces totalling around 34 minutes which have never been officially released. The music offers the same spectral timbres that you hear on the group’s early kosmische albums—Alpha Centauri (1971), Zeit (1972) and Atem (1973)—and is close enough to the atmospherics of Zeit to sound like rehearsals for their droning meisterwerk.

The existence of the music always raised the question of what Vampira might actually look like, especially when the musicians sound as though they’re playing more for themselves than accompanying anything on a screen. Moorse’s film is stranger than the low-budget horror I was expecting. The first thing we see is Manfred Jester, a bespectacled man surrounded by old books, who proceeds to describe (in unsubtitled German) the history of vampires. After a minute of two of this there’s a cut to the first interlude which illustrates the preceding sequence—or so I’m guessing since I had to rely on my rudimentary schoolboy German to understand what Herr Jester was talking about. The rest of the film follows this format: a minute or two of Jester’s lecturing (with references to the Tarot, Montague Summers, Baudelaire and so on) separated by dramatised interludes, all of which are scored by Tangerine Dream. The dramatisations are the oddest part of the whole enterprise. Aside from the music these sequences are almost completely silent (with one brief exception), and acted in a manner which is more symbolic than conventionally dramatic, giving the appearance in places of Kenneth Anger directing one of Jean Rollin’s vampire films. Moorse’s visuals are quite striking in places; if you clipped out all the Jester sequences you’d have 34 minutes of languid Gothic weirdness with a kosmische soundtrack.

The remaining mystery is why the film and its music have been buried for so long, especially when the Tangerine Dream estate has been releasing old recordings for the past few years. I’d guess that the tapes have been lost, but then the same might once have been said about the 1974 Oedipus Tyrannus score until the whole thing was released for the first time six years ago. Vampira was so scarce that I thought it too might have been lost for good, or destroyed like many of the BBC productions from the early 1970s. The music was at least available in unofficial form in the Tangerine Tree bootleg set, a fan-made series which still circulates today if you know where to look. Many of the Tangerine Tree concerts have since been officially reissued, as have other soundtrack recordings the group made for German television. More recently, the Vampira score turned up on another bootleg, a vinyl release limited to 38 copies. All the isolated cues don’t provide a great deal of music for a standalone album but any future release which added the short Oszillator Planet Concert (which also dates from 1971) would push things to a more substantial 42 minutes. It’s likely that the Vampira music was originally a single improvised piece that was then edited to match the film; the pieces certainly blend very easily if you mix their beginnings and ends together.

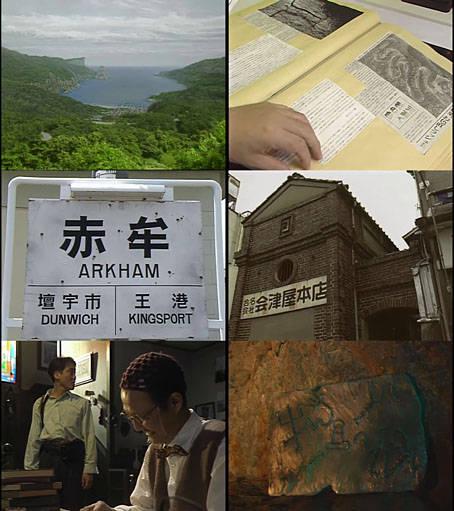

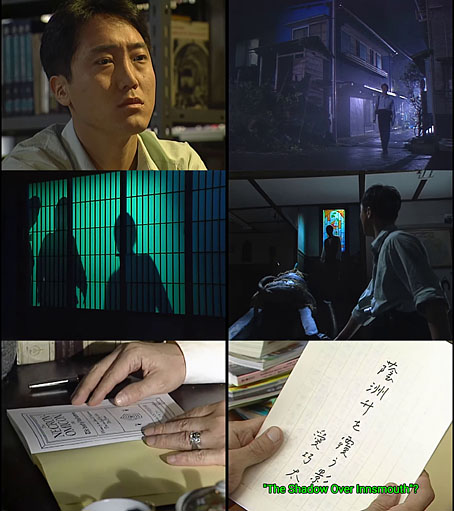

George Moorse followed Vampira with many more TV films including HP Lovecraft: Schatten aus der Zeit (1975), an adaptation of The Shadow Out of Time starring Anton Diffring. Now that I’ve finally seen the vampire film I’m a little more inclined to see how Moorse treats Lovecraft.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Cosmic music and cosmic horror

• Tangerine Dream in concert

• Drone month

• Pilots Of Purple Twilight

• A mix for Halloween: Analogue Spectres

• Edgar Froese, 1944–2015

• Tangerine Dream in Poland