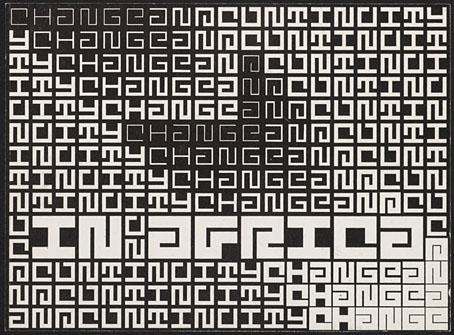

Labyrinth (Westminster) by Mark Wallinger.

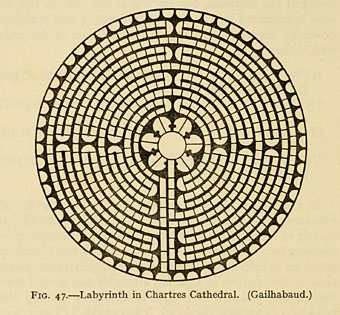

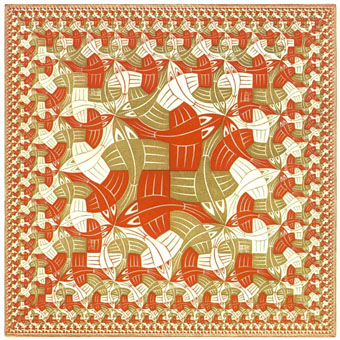

A mandatory post, this one, seeing as how it combines two continual sources of interest: labyrinths and the London Underground transport system. Transport for London commissioned artist Mark Wallinger to create something for the 150th birthday celebrations of the Tube, the result being a series of 270 different labyrinth designs, one for each of the capital’s stations. Needless to say, I like the idea, and it’s been interesting to see that some of Wallinger’s designs hark back to earlier labyrinths. The one for the Westminster station is notable for the way it references the famous Chartres Cathedral labyrinth (below)—a nod to Westminster Abbey, perhaps—and also features an enclosed and inaccessible loop, a possible comment on the irresolvable dealings occurring across the road in the Houses of Parliament.

It’s Nice That has more of Wallinger’s designs while Creative Review draws attention to an earlier maze design on the wall at Warren Street station.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Cthulhu Labyrinth

• The labyrinth of Versailles

• Maze and labyrinth panoramas

• Mazes and labyrinths

• Labyrinths

• Jeppe Hein’s mirror labyrinth