Day of the Dead

| Robert Hughes excoriates Damien Hirst.

Tag: Robert Hughes

Two steps forward, one step back

My apologies to any visitors arriving here during the past week to find the site down. What should have been a straightforward upgrading of the hosting service became overly-extended due to compounded misunderstanding and poor communication. It didn’t help that I was also extremely busy catching up with work after the long bank holiday weekend.

By way of catching up with the posting, anyone interested in Francis Bacon’s art is advised to go and read this excellent appraisal by my favourite art critic, Robert Hughes, a taster for the forthcoming Bacon exhibition at Tate Britain. The exhibition will run from 11 September, 2008 to 4 January, 2009.

Robert Rauschenberg, 1925–2008

Retroactive I (1964).

My youthful enthusiasm for art acquainted me with the name of Robert Rauschenberg (who died two days ago) earlier than most. Surrealism and Pop Art held an appeal that was immediate, if rather superficially appreciated at the time, and it was seeing works from both those movements which were the most memorable aspect of my first visit to the Tate Gallery when I was 13. Later on when I was reading JG Ballard’s stories and essays in back numbers of New Worlds, Rauschenberg was one of a handful of artists who seemed to depict in visual terms what Ballard was describing in words. In this respect Robert Hughes’s discussion of the “landscape of media” (Ballard’s common phrase would be “media landscape”) below is coincidental but significant. Retroactive I was painted a couple of years before Ballard began the stories that would later become The Atrocity Exhibition and it could easily serve as an illustration for that book.

There are and will be plenty of words written elsewhere about Rauschenberg’s work and influence. I’ll note here his inclusion in the list of gay artists at GLBTQ for his creative and personal partnership with another great Pop artist, Jasper Johns.

One of the artists (television) most affected in the Sixties was Rauschenberg. In 1962, he began to apply printed images to canvas with silkscreen—the found image, not the found object, was incorporated into the work. “I was bombarded with TV sets and magazines,” he recalls, “by the refuse, by the excess of the world … I thought that if I could paint or make an honest work, it should incorporate all of these elements, which were and are a reality. Collage is a way of getting an additional piece of information that’s impersonal. I’ve always tried to work impersonally.” With access to anything printed, Rauschenberg could draw on an unlimited bank of images for his new paintings, and he set them together with a casual narrative style. In heightening the documentary flavour of his work, he strove to give canvas the accumulative flicker of a colour TV set. The bawling pressure of images—rocket, eagle, Kennedy, crowd, street sign, dancer, oranges, box, mosquito—creates an inventory of modern life, the lyrical outpourings of a mind jammed to satiation with the rapid, the quotidian, the real. In its peacock-hued, electron-sweetbox tints, this was an art that Marinetti and the Berlin Dadaists would have recognized at once: an agglomeration of memorable signs, capable of facing the breadth of the street. Their subject was glut.

Rauschenberg’s view of this landscape of media was both affectionate and ironic. He liked excavating whole histories within an image—histories of the media themselves. A perfect example is the red patch at the bottom right corner of Retroactive I. It is a silkscreen enlargement of a photo by Gjon Mili, which he found in Life magazine. Mili’s photograph was a carefully set-up parody, with the aid of a stroboscopic flash, of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912. Duchamp’s painting was in turn based on Marey‘s photos of a moving body. So the image goes back through seventy years of technological time, through allusion after allusion; and a further irony is that, in its Rauschenbergian form, it ends up looking precisely like the figures of Adam and Eve expelled from Eden in Masaccio’s fresco for the Carmine in Florence. This in turn converts the image of John Kennedy, who was dead by then and rapidly approaching apotheosis as the centre of a mawkish cult, into a sort of vengeful god with a pointing finger, so fulfilling the prophecy Edmond de Goncourt confided to his journal in 1861:

“The day will come when all the modern nations will adore a sort of American god, about whom much will have been written in the popular press; and images of this god will be set up in the churches, not as the imagination of each individual painter may fancy him, but fixed, once and for all, by photography. On that day civilization will have reached its peak, and there will be steam-propelled gondolas in Venice.”

Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New (1980).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Transfer drawings by Robert Rauschenberg

• Jasper Johns

• Michael Petry’s flag

• JG Ballard book covers

Dirty Dalí

The paranoiac-critical gaze: Dirty Dalí.

I finally managed to see this fascinating documentary this week. Since my TV broke down some time ago I refused to waste money buying another, partly for the reason that films such as this are increasingly rare and most of them have been shunted to minority channel BBC 4 which I can’t receive. Thanks to BitTorrent you can still find the worthwhile stuff, of course, but this often requires patience.

The Wines of Gala and of God (1977).

Dirty Dalí: A Private View was a reminiscence by art critic Brian Sewell about his encounters with Dalí and wife Gala at their home in Port Lligat in the late 60s and early 70s. What’s interesting about it is the first-hand light it throws on Dalí’s complicated sexuality, a subject which has been the source of speculation in biographies (notably Ian Gibson’s The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí) but which is confused by the artist’s simultaneous revealing of his obsessions in his art and the veiling of his interests in public statements, not least the frequent declarations of impotence. Sewell confirms that Dalí was interested in both men and women although purely as a voyeur, and relates how his first encounter with the artist led to his having to lie naked in the armpit of a giant Christ sculpture in Dalí’s garden, masturbating while Dalí took photographs. Sewell also examines Dalí’s affair with Federico García Lorca, the closest the artist came to a gay romance, and his subsequent relationship with Gala, which became one where the pair used the artist’s celebrity to attract delectable people of both sexes, like a pair of art world super-swingers. According to Sewell, Dalí’s physical ideal was the hermaphrodite which would possibly explain his attraction to (alleged) transsexual Amanda Lear during this time.

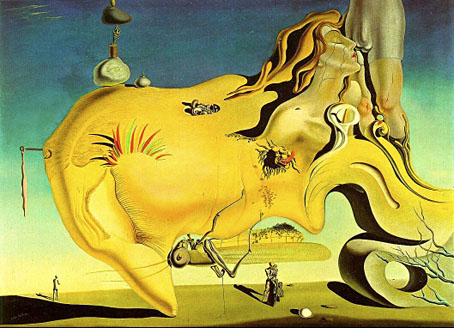

The Great Masturbator (1929).

As a piece of television the film struggles to fill out its running time by resorting to animating photographs, a persistent hazard for documentaries that lack the relevant raw material. All the footage of Dalí is lifted from previous documentary films including a large chunk of Russell Harty’s Aquarius interview, Hello Dali! (that camp double-entendre now seems very apt), from 1973. The overall effect of Sewell’s narrative is to add to Dalí’s already considerable feet of clay but that’s the inevitable outcome of nearly any biography; real lives are always messy. Sewell nonetheless ends by reaffirming Dalí’s principal importance as one of the great painters of the 20th century and, in an interesting side note, declares him to be the last great painter of a religious work with his Christ of St John of the Cross. A great religious artist and also one who produced hundreds of pornographic drawings, some of which are seen in the film. In art, as in the life, the contradictions are everywhere.

• Dirty Dalí at Grey Lodge

• Homage to Catalonia: Robert Hughes on Dalí

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie revisited

• Dalí and Film

• Ballard on Dalí

• Fantastic art from Pan Books

• Penguin Surrealism

• The Surrealist Revolution

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie

L’Amour Fou: Surrealism and Design

Cadeau Audace by Man Ray (1921).

L’amour fou by Robert Hughes

Fur teacups, wheelbarrow chairs, lip-shaped sofas … the fashion, furniture and jewellery created by the Surrealists were useless, unique, decadent and, above all, very sexy.

The Guardian, Saturday March 24th, 2007

THE VICTORIA AND Albert’s big show for this year, Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design, is—well, maybe we don’t much like the word “definitive”. But it’s certainly the first of its kind.

Everyone knows something about surrealism, the most popular art movement of the 20th century. The word has spread so far that people now say “surreal” when all they mean is “odd”, “totally weird” or “unexpected”. No doubt this would give heartburn to André Breton, the pope of the movement nearly a century ago, who took the title from his friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had called his play The Breasts of Tiresias, “a surrealist drama”. But too late now. The term is many years out of its box and, through imprecision, has achieved something akin to eternal life. Surrealist painting and film, that is. In fact, some surrealist images have imprinted themselves so deeply and brightly on our ideas of visual imagery that we can’t imagine modern art (or, in fact, the idea of modernity itself) without them.

Think Salvador Dalí and his soft watches in The Persistence of Memory. Think Dalí again, in cahoots with Luis Buñuel, and the cut-throat razor slicing through the girl’s eye, as a sliver of cloud crosses the moon (actually, the eye belongs to a dead cow, but you never think this when you see their now venerable but forever fresh movie An Andalusian Dog, 1929). Think of photographer Man Ray’s fabulous Cadeau Audace (‘Risky Present’, 1921), the flatiron to whose sole a row of tacks was soldered, guaranteeing the destruction of any dress it would be used on. Think of Rene Magritte’s The Rape, that hauntingly concise pubic face, with nipples for eyes and the hairy triangle where the mouth should be. Think of the shock, the horniness, the rebellion, the unwavering focus on creative freedom, the obsessive efforts to discover the new in the old by disclosure of the hidden…

Continues here

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealist Revolution

• Surrealist Women

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Surrealist cartomancy