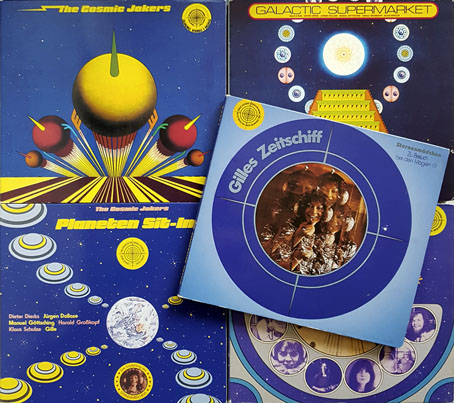

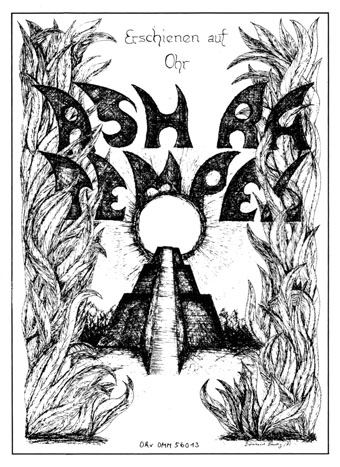

Where Monday’s post was about the cosmic music of the 1970s, this one concerns something in the same zone that’s more contemporary. Chad Davis is an American musician who likes to compartmentalise his activities as separate projects with different names. Jenzeits is Davis in kosmische mode, drawing heavily on the Berlin School of electronica and similar music of the 1970s, with a name that collides Jenseits, a title from Join Inn, the fourth album by Ash Ra Tempel, with Zeit, the third album by Tangerine Dream. (“Jenseits” is the German word for beyond, while “zeit” means time, so “Jenzeits” might be taken as a pun meaning “beyond time”. German speakers, however, may see this less as a pun than simply poor use of their language.)

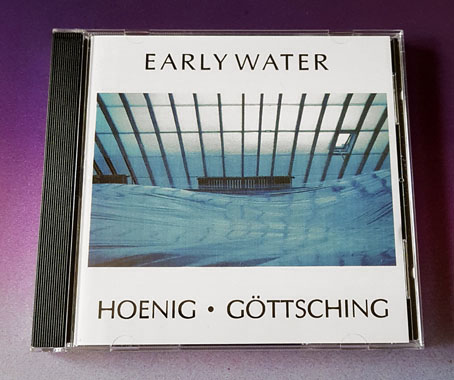

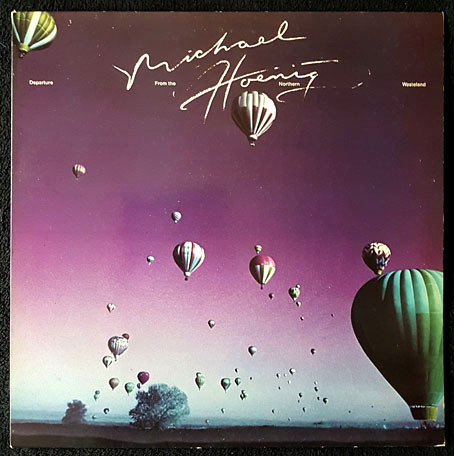

There’s been a lot of Berlin-School pastiching going on over the past few years, the mid-70s albums by Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze being very popular among the period imitators. I’m always referring to Redshift and Node as my favourite exponents in this idiom. Chad Davis is obviously inspired by the same albums but my attention was caught on a first hearing by his homages to the music that Manuel Göttsching was making under the Ash Ra Tempel/Ashra name during the same period, especially Le Berceau De Cristal, New Age Of Earth, and (to a lesser extent) Blackouts. Göttsching was always primarily a guitar player, but by the mid-70s he was combining his guitar work with sequencers and synthesizers to create instrumental electronic music with a different texture to his keyboard-based contemporaries. New Age Of Earth has a hippyish title that might be off-putting to curious listeners but it’s long been one of my favourite electronic albums, with a unique atmosphere that I wish Göttsching had pursued a little further. (The title in German on the back of the original French release is Neuzeit der Erde, literally “New Time of Earth”. Zeit again.) The album’s unique qualities are a product of its blend of processed guitar, keyboards and electronic rhythms, the latter being created by the EKO Computerhythm, an early programmable drum machine which could also be used to trigger other instruments to create sequencer patterns.

New Age Of Earth (1976). Design by Peter Butschkow.

I can’t say for certain whether Davis had this music or instrumentation in mind when recording his third Jenzeits album, Jenzeits Cosmic Orbits, but the similarities were enough to make me want to hear more. One of the frustrations of electronic music historically has been the way the evolution of technology has dictated its form. Tangerine Dream’s music changed according to the instrumentation they had available at any given time; new equipment meant new sounds and musical possibilities very different to the ones the group had been exploring a couple of years before. This doesn’t happen to the same degree with other musicians, especially guitarists who are often happy to play the same battered instrument for years on end. For a listener, the technical evolution of electronic music has often left behind abandoned areas or unexplored avenues. In this respect, the music of Jenzeits is less a series of pastiches than an attempt to further some of these explorations.

There are 12 Jenzeits releases to date, all of which are available on Bandcamp. Some of the earlier ones have also appeared on vinyl and cassette. If a CD box of the entire Jenzeits catalogue appeared I’d buy it in a second but I doubt this will happen any time soon. For the curious, Jenzeits Volume 1 is a good place to start. The last Jenzeits release was in 2020 which suggests we’ve seen the end of this particular project. For those who’d like more (and I still do), an earlier Chad Davis project, Romannis Mötte, ventured into similar territory.

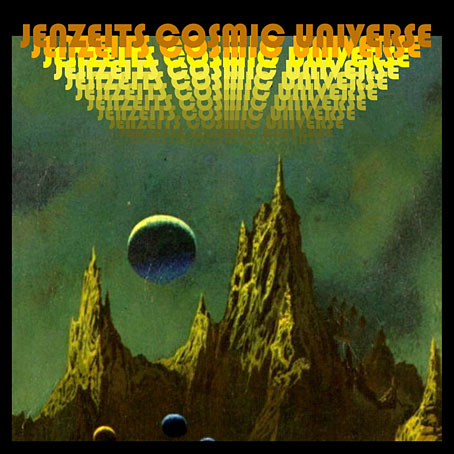

Jenzeits Cosmic Universe (2017).

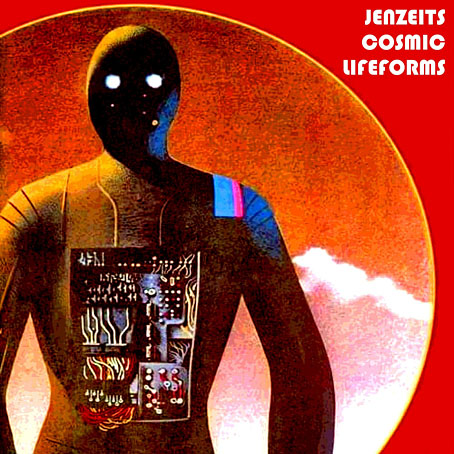

Jenzeits Cosmic Lifeforms (2017).

Jenzeits Cosmic Orbits (2017).