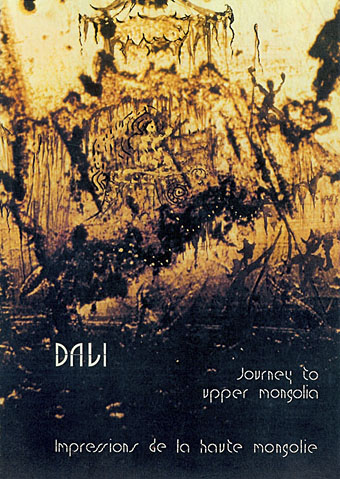

Impressions de la Haute Mongolie – Hommage á Raymond Roussel (1974-75).

When I wrote a short reminiscence about Impressions de la Haute Mongolie last March I really didn’t expect I’d be watching it again just over a year later having waited thirty years for the opportunity. But now we can all see José Montes-Baquer’s collaboration with Salvador Dalí, thanks to the indispensable Ubuweb. The copy there doesn’t have English subtitles, unfortunately, but the visuals are still beguiling and not too difficult to follow if you can understand some French and Spanish. It was a curious experience seeing this again, some parts I remembered very well, others I’d completely forgotten about. Most surprising was the soundtrack of electronic music, much of it taken from recordings by Wendy Carlos, including a part of her ambient Sonic Seasonings suite and portions of her complete score for A Clockwork Orange. There’s more about this deeply strange film in Tate Etc.

And speaking of surreal landscapes, it’s worth mentioning that I’ve spent the past few weeks working on a new piece of Lovecraft-themed artwork for an exhibition at Maison d’Ailleurs, the Museum of science fiction, utopia and extraordinary journeys in Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland. The exhibition of newly-commissioned work based on themes from HP Lovecraft’s Commonplace Book will be launched in October 2007. More details about the event, and my contribution, closer to that date. In the meantime, the European edition of TIME magazine has a short feature about the gallery and its ethos.

Previously on { feuilleton }

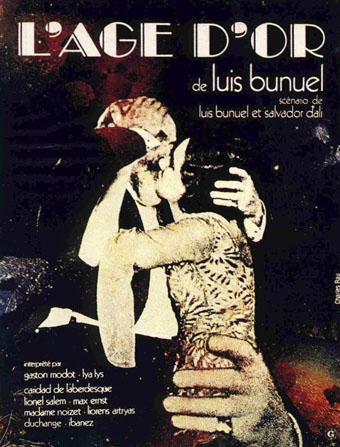

• Dalí and Film

• Ballard on Dalí

• Fantastic art from Pan Books

• Penguin Surrealism

• The Surrealist Revolution

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie