Cockfighter is a film by Monte Hellman from American cinema’s great decade (the Seventies) that we’re not allowed to see in this country because it contains cruelty to chickens. This week the Edinburgh International Film Festival halted a planned screening after being informed it contravened a 1937 law:

Cockfighter is a film by Monte Hellman from American cinema’s great decade (the Seventies) that we’re not allowed to see in this country because it contains cruelty to chickens. This week the Edinburgh International Film Festival halted a planned screening after being informed it contravened a 1937 law:

Change to Programmed Performance: Cockfighter

Mon 21 Aug 2006

Due to interesting circumstances we are unable to screen COCKFIGHTER (70’s retrospective) on TUESDAY 22 August.

This will be replaced by Monte Hellman’s TWO LANE BLACKTOP (1971) in a spanking new preservation print. Huge thanks to Universal for giving us this and to the BFI for help in sourcing it.

COCKFIGHTER contains scenes which contravene the CINEMATOGRAPHIC FILMS(Animals) ACT 1937 whereby it is a criminal offence to screen the film to the public (whether they pay or not).

We apologise for the disappointment this may cause. The film was never certificated in the UK because it was impossible to deliver a cut that would not contravene the Act.

We were unaware of this combination of circumstances when we programmed the film.

We’re not chicken; it’s the cinema license holder who would prosecuted and as that isn’t me, I’d prefer to take the prudent route.

Ginnie Atkinson, Managing Director, EIFF

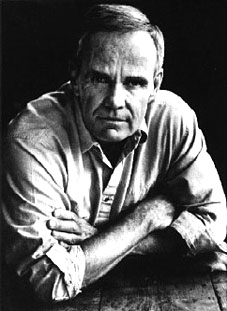

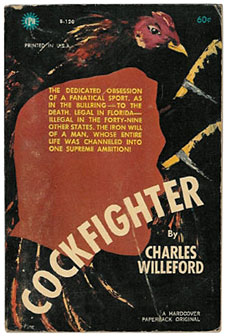

Monte Hellman is a serious director and the film has been lauded by other directors and critics such as Alex Cox who praise Hellman’s direction and Warren Oates’ performance. The screenplay was by Charles Willeford based on his novel and the film also features Harry Dean Stanton who was in Hellman’s earlier Two Lane Blacktop.

While I’m not desperate to see chickens pecking and clawing themselves to death, I’d prefer to be allowed a choice of whether I can or not. For some reason odd films like this get singled out yet other films of the period that contain images of violence to animals get by. Offhand I can think of the shooting and slaughter of a buffalo in Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, chickens having their heads shot off in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, and the slow-motion slaughter of a caribou in Apocalypse Now. The Guardian says:

A BBFC spokesman said that The [Cinematograph Films (Animals) Act 1937] made it illegal to show any scene which was organised or directed for the purpose of the film involving cruelty to animals. The Act was originally introduced following complaints that horses were deliberately made to fall in Hollywood westerns.

This seems inconsistent given that the Peckinpah film certainly had chickens killed for the purposes of that scene. Maybe it’s not counted as cruelty if you blow off their heads rather than let them attack each other? I wonder how many of the people who’ve enforced this rule over the years have been chicken eaters? Anyway, this nonsense aside, Anchor Bay has had the film available on DVD for a while and Willeford’s novel is also in print.