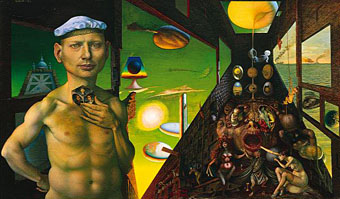

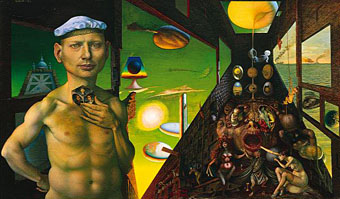

Die Arche des Odysseus (1948–1956).

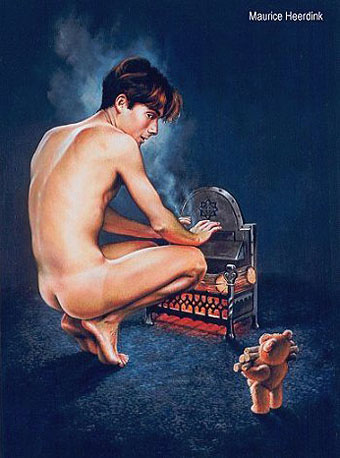

Adam Bei Sich (1969).

A major Austrian painter and printmaker, Rudolf Hausner studied art at the Academy in Vienna from 1931 to 1936, under Fahringer and Sterrer. Many of his early paintings were confiscated and branded as ‘degenerate’ by the ruling Nazi party in 1938. In 1941 Hausner was drafted by the German army and remained a soldier until the war’s end in 1945. After the war he returned to Vienna and immersed himself in studies dealing with the unconscious and with the art of Surrealists, particularly that of Max Ernst. Along with Wolfgang Hutter and Anton Lehmden, Rudolf Hausner founded the Viennese School of Fantastic Realism in 1947. During the 1950s and 1960s this became one of Austria’s most important movements and Hausner was its most influential artist. During this time he also held principal teaching posts at the academies of Vienna and Hamburg.

Equally gifted as a painter, lithographer and etcher, Hausner’s complex art is based upon potent symbols and imagery. Primary among these is the constantly recurring image of the first man, Adam, who is part autobiographical and part archetype. Another compelling image is that of the man or boy in a sailor’s cap. Hausner claimed that this image symbolized the myth of Odysseus and his epic voyages on the seas. It also, however, is representative of the artist’s own boyhood and the integrated relationships of youth and age within the self.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive