The White House, Washington DC, on the evening of June 26, 2015.

I can remember that after the cops cleared us out of the bar we clustered in Christopher Street around the entrance to the Stonewall. The customers were not being arrested, but a paddy wagon had already hauled off several of the bartenders. Two or three policemen stayed behind, locked inside with the remaining members of staff, waiting for the return of the paddy wagon. During that interval someone in the defiant crowd outside called out “Gay Power”, which caused us all to laugh. The notion that gays might become militant after the manner of blacks seemed amusing for two reasons—first because we gay men were used to thinking of ourselves as too effeminate to protest anything, and second because most of us did not consider ourselves to be a legitimate minority.

At that time we perceived ourselves as separate individuals at odds with society because we were “sick” (the medical model), “sinful” (the religious model), “deviant” (the sociological model) or “criminal” (the legal model). Some of these words we might have said lightly, satirically, but no amount of wit could convince us that our grievances should be remedied or our status defended. We might ask for compassion but we could not demand justice. Many gays either were in therapy or felt they should be, and the words gay liberation would have seemed as preposterous to us as neurotic liberation (now, of course, Thomas S. Szasz in the United States, RD Laing in Britain and Felix Guattari on the Continent have, in their different ways, made even that phrase plausible enough).

What I want to stress is that before 1969 only a small (though courageous and articulate) number of gays had much pride in their homosexuality or a conviction that their predilections were legitimate. The rest of us defined our homosexuality in negative terms, and those terms isolated us from one another. We might claim Plato and Michelangelo as homosexuals and revere them for their supposed affinities with us, but we could just as readily dismiss, even despise, a living thinker or artist for being gay. Rich gays may have derived pleasure from their wealth, educated gays from their knowledge, talented gays from their gifts, but few felt anything but regret about their homosexuality as such. To be sure, particular sexual encounters, and especially particular love relationships, were gratifying then as now, but they were explained as happy accidents rather than as expected results.

Edmund White writing on The Political Vocabulary of Homosexuality (1980). Reprinted in The Burning Library: Writings on Art, Politics and Sexuality (1994).

• “…after seeing Don’t Look Now, The Wicker Man looked just so dull and flat. What Don’t Look Now has that The Wicker Man doesn’t is a complete mastery of cinema. Don’t Look Now is almost a silent movie, a brilliant, coherent, original and fantastic film that has an enormous emotional impact.” Bernard Rose emoting at length about Nicolas Roeg. Related: Wild Hearts Run Out Of Time, the Roy Orbison video that Rose mentions directing.

• “The male sex organ is depicted not so much as a body part, but more as a fetish object in its own right—a thing independent of the male body, worthy of intense, delirious veneration.” Jason Farago reviewing Tom of Finland: the Pleasure of Play. Related: Same-sex desire through the ages at the British Museum.

• “Sphinx is a typical love story only in the way that it’s the tale of two people who have fallen in love, and things don’t go smoothly. Beyond that…as reader, you have no idea of the gender of either half of this romantic equation.” Chris Clarke reviewing Sphinx, a novel by Anne Garréta.

• “To give space to the musical elements was really a thrill—how far can you get without using too much stuff?” Moritz von Oswald on “the sounds of emptiness”.

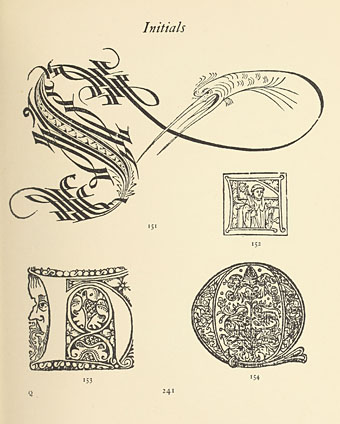

• “The problem is not always Helvetica but that Helvetica is all too often the default, the fall-back, the I-really-can’t-be-arsed choice,” says John Boardley.

• Mix of the week: Shaft’s Old Man: An Imaginary Soul Jazz Soundtrack by Aquarium Drunkard.

• “What is the Cut-Up Method?” Ken Hollings explains in a BBC magazine piece and radio feature.

• Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass, the final TV serial, will be released on Blu-ray next month.

• Relevant to the week’s reading: an archived Italo Calvino site.

• Drÿad: a Tumblr.

• Sphinx (1989) by Syd Straw | The Sodom And Gomorrah Show (2006) by Pet Shop Boys | Pattern 1 (2009) by Moritz Von Oswald Trio