The best films never made | David Lean’s Nostromo? Michael Powell’s The Tempest?

Tag: Michael Powell

Scorsese: my friendship with Michael Powell

Scorsese: my friendship with Michael Powell | Marty, Michael and the splendour of The Red Shoes.

Jack Cardiff, 1914–2009

Robert Helpmann, Moira Shearer and Léonide Massine; The Red Shoes (1948).

Jack Cardiff, who died this week, was one of the great cinematographers from the postwar era, a period when British cinema was raised for a time to world-class level. His three films for the Archers, aka Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, are masterpieces of Technicolor photography. He won an Oscar for one of these, Black Narcissus, while his photography in The Red Shoes includes Moira Shearer’s 18-minute ballet performance, one of the most strikingly surreal sequences in the whole of British film.

Cardiff taught himself about lighting from scrutinising the Old Masters and the Impressionists, and teaching himself to observe colour, shade and reflection in everyday things. “As they say, ‘Love comes by looking’, and I was looking all the time. That’s how you learn.” He picks up one of the dozens of books on Rembrandt that he owns and draws my attention to the exquisitely painted shadow of a nose in one of his favourite portraits. We look at the interiors of other Dutch masters – Pieter De Hooch, Vermeer. It was to the work of Vermeer that the starkly beautiful images of nuns he created for his Oscar-winning movie Black Narcissus (1947) were likened.

Elizabeth Lowenthal, The Independent, 1994.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Deborah Kerr, 1921–2007

• Freddie Francis, 1917–2007

Deborah Kerr, 1921–2007

The Innocents.

A great British actress died this week. She was also something of a movie star in the Fifties, rolling in the surf with Burt Lancaster in From Here to Eternity (1953) and standing up to Yul Brynner in The King and I (1956). Prior to that she starred in two films for Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) (where she played three roles) and Black Narcissus (1947). But for me she’ll always be the (literally) haunted Miss Giddens in The Innocents (1961), Jack Clayton’s superb adaptation of The Turn of the Screw. Still one of the most effective screen ghost stories; try and see it this Halloween.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Freddie Francis, 1917–2007

Occultism for kids

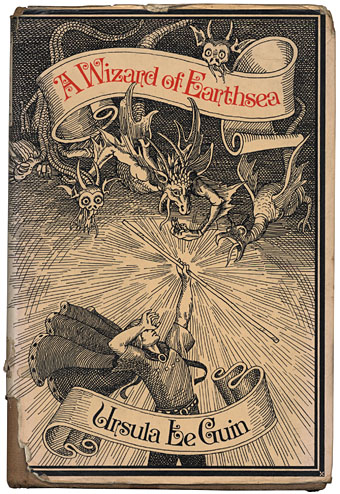

My battered 1973 Gollancz hardback. Cover illustration by David Smee.

It may be all Harry Potter starter homes crowding the imaginative landscape these days but the lush fields of the early Seventies bred a peculiar brand of wizardry and wild romance, something I was reminded of recently by reviews of a new compilation of psychedelic singles (yes, another one), Real Life—Permanent Dreams on the Castle Communication label. Mention of a curio from the heady days of 1970, Tarot by Andrew Bown, summoned vague memories of a childrens’ television series, Ace of Wands, for which Tarot was the theme song. You can see the title sequence here and this clip compilation features the whole song plus trippy lyrics (“Velvet roofs, tattooed skies, patterns made from words…”). The wonderfully facetious TV Cream describes the series thus:

ACE OF WANDS (1970–72), THAMES TELEVISION. Jim-Morrison-alike boy magician Tarot (MICHAEL MACKENZIE) has adventures through history, for which read cheap studio set representing pyramid, cheap studio set representing Stonehenge and so on. DR WHO-style menace on a budget. Fought enemies such as Madame Midnight, Mr Stabs and Mama Doc, aided by an owl called Ozymandias (played by FRED THE OWL). Tarot cards and tarot phenomena abounded, much worthy roustabouts ensued. Prog-heavy title theme babbling – “Jet white dove/Snow black snake/Time has turned his face/From the edge of mystery” – singularly failed to assault the charts.

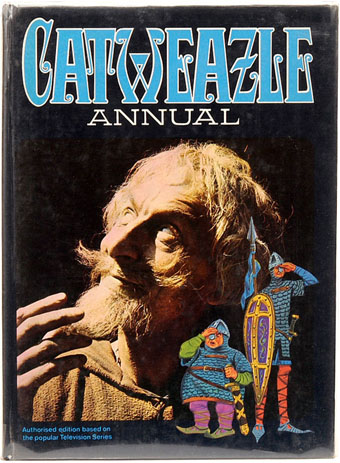

I’ve mentioned before how magic and occultism were more popular at this time than they’ve probably ever been, and this flush of popularity, much of it coming from underground culture, managed to work its way into children’s television in a diluted form. Ace of Wands is easily the most baroque example of this, mixing the bell-bottom trendiness of Jason King with pulp plots given a psychedelic twist (hallucinogenic gases anyone?). Also from 1970 and far more down-to-earth (and, it should be said, more fun for kids) was Catweazle, written by Richard Carpenter and starring Geoffrey Bayldon. TV Cream has the details again:

I’ve mentioned before how magic and occultism were more popular at this time than they’ve probably ever been, and this flush of popularity, much of it coming from underground culture, managed to work its way into children’s television in a diluted form. Ace of Wands is easily the most baroque example of this, mixing the bell-bottom trendiness of Jason King with pulp plots given a psychedelic twist (hallucinogenic gases anyone?). Also from 1970 and far more down-to-earth (and, it should be said, more fun for kids) was Catweazle, written by Richard Carpenter and starring Geoffrey Bayldon. TV Cream has the details again:

CATWEAZLE (1970–71), LWT. Hairy tinker who can’t speak but who’s really an 11th Century magician (and who’s really GEOFFREY BAYLDON) tries to escape from some pissed off Norman soliders, jumps in a pond to hide and finds himself transported to Children’s Film Foundation-era Britain. Luckily there’s a posh (as always) boy on hand to explain all our modern day shit to him.

Catweazle quickly became the most popular kids’ progamme of its day and part of its attraction was the way in which Bayldon’s Norman time-traveller mistranslated modern technology as magic. So the telephone became a device called the “telling bone”, electricity was “electrickery” and so on. I had the first Catweazle annual which was an odd mixture of comic strips, text stories and articles about stage magicians with a smattering of genuine occult history.

Catweazle quickly became the most popular kids’ progamme of its day and part of its attraction was the way in which Bayldon’s Norman time-traveller mistranslated modern technology as magic. So the telephone became a device called the “telling bone”, electricity was “electrickery” and so on. I had the first Catweazle annual which was an odd mixture of comic strips, text stories and articles about stage magicians with a smattering of genuine occult history.

Best of all for this Seventies kid was my favourite reading on the frequently dull Jackanory (“Ramshackle reading-is-fun relic wherein a Famous Person would sit on a chair with a pretend book and ponderously recount the contents of your local mobile library” says TV Cream) which one week had Ursula K Le Guin‘s A Wizard of Earthsea as its featured book. Try as I might, I’ve been unable to find the name of the actor who read this (black clothes, medieval chair) but I was knocked out by it. Years later the Earthsea cycle is still the only work of Le Guin’s I’ve been able to read, her science fiction seemed boring by comparison.

The inflated success of Harry Potter has had people casting about for JK Rowling’s influences over the past few years. A Wizard of Earthsea was first published in 1968 and also concerns a school of wizards, as do several other pre-HP novels. Rowling has acknowledged this although that acknowledgement hasn’t been loud or regular enough to appease a grouchy Le Guin. The Earthsea books are a lot shorter than the Potter door-stops and the first book at least is rather more sophisticated, reading equally well as a fantasy adventure for children and as a Jungian fable for adults with hints of Buddhist or Taoist philosophy. The characters are also notable for not being the Caucasians that most fantasy characters usually are, one of many details a recent TV adaptation (which Le Guin condemned) managed to ignore. It’s worth noting that JK Rowling is part of my generation (I’m 45, she’s 42) so she would have watched all this Seventies stuff herself. One of the reasons fantasy readers and writers (as opposed to snooty broadsheet critics) are often disappointed by the Potter juggernaut is that it could have been so much more considering the wealth of precedent that it draws upon. But then books rarely achieve this scale of popularity without being conservative and undemanding, Rowling’s work is merely the most recent example of this.

Le Guin spoiled the impact of her excellent first Earthsea book with several sequels of diminishing interest. A new animated film from Japan, Gedo Senki or Tales from Earthsea, based on the later works is released in the UK this month. The great British director Michael Powell had plans for an Earthsea adaptation scripted by Le Guin when he was director in residence at Francis Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios in 1980. Powell was great with fantasy (watch his Thief of Bagdad) so it’s a shame that nothing came of this. Ace of Wands is on DVD now and so is Catweazle. I can’t vouch for the former having much value beyond pure nostalgia but there’s plenty of clips from the latter at YouTube. Proceed with caution.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Bob Pepper

• Of Moons and Serpents

• Austin Osman Spare