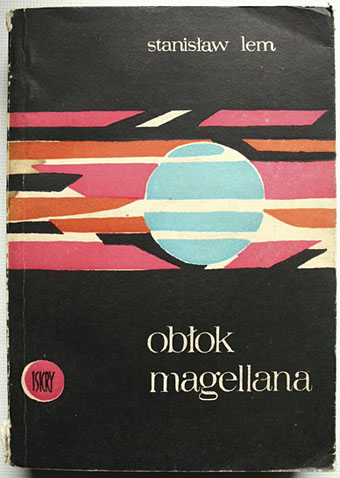

A science fiction novel by Stanislaw Lem (The Magellanic Cloud, 1955).

Illustration by Teodor Rotrekl.

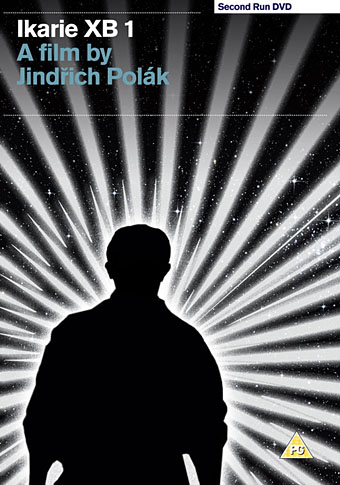

A film by Jindrich Polák, adapted from Lem’s novel by Polák and Pavel Jurácek. (1963).

A Second Run DVD (2013).

With the exceptions of Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Stalker (both in a league of their own), I’ve never been very enthused about Eastern Bloc science-fiction cinema. If I hadn’t been watching some Czech films recently, and listening to the soundtrack music of Zdenek Liska, I might not have bothered with this one despite its being promoted as a visual influence on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Ikarie XB 1 won the Grand Prize at the Trieste International Science Fiction Film Festival in 1963, a tie with Chris Marker’s La Jetée. (Umberto Eco was one of the judges.) Fifty years on, Marker’s film has hardly dated at all while Ikarie XB 1 seems very much of its time. But Polák’s film still has some things going for it, surprisingly so considering the director was more used to making comedies.

Ikarie XB 1 is a spaceship travelling to Alpha Centauri in the year 2163. The DVD subtitles don’t translate the name Ikarie so unless you already know it means “Icarus” there’s no foreshadowing of any possible threat, at least until the opening shots of a deranged crewman stumbling through empty corridors. Many of the scenes which follow seem over-familiar but only because the scenario of space-crew as interstellar family has become such a standard feature of filmed space opera from Star Trek on. The production design is dated, of course, but the film makes great use of black and white in the lighting patterns, on-screen visuals, clothing designs, etc. It’s easy to see why Kubrick thought it was a cut above other SF films of the period, especially with its widescreen compositions. The DVD booklet (and Kim Newman’s interview on the disc) mention Kubrick’s stylistic borrowings; judge for yourself with these screen-grabs. I was hoping the Liska soundtrack might be more electronic than it is. It’s very much a Liska score—at times you can’t help but imagine a Svankmajer puppet lurking round a corner—but with added reverb and spectral organ chords. The latter assist a sequence where two of the crew members explore an apparently derelict space station.

This page reviews the film in some detail (complete with plot spoilers). For the curious, the entire film is a free download at the Internet Archive.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Fiser and Liska

• Two sides of Liska

• Liska’s Golem

• The Cremator by Juraj Herz