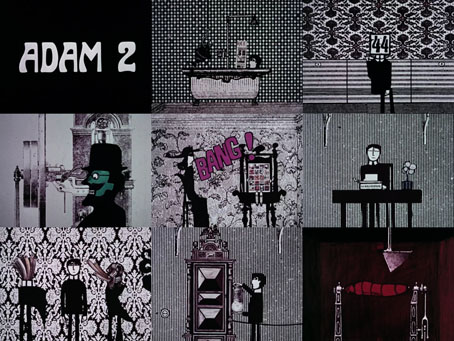

Adam 2 is the first feature-length animated film by Polish animator and graphic designer Jan Lenica (1928–2001). The film was a German production, made in 1968 after Lenica had spent the past decade making shorter films in Poland, several of which look like rehearsals for this one.

Lenica called it “a sort of an intellectual comic strip”. A trip across ages and spaces, remindful of the biblical Paradise; a struggle for one’s individuality; a parody of Stalinism and totalitarianism. Critics emphasized the pessimism of its message. (More)

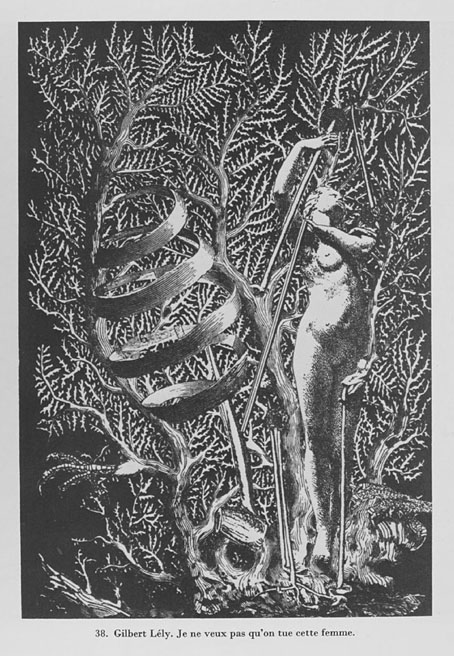

A pair of title cards at the beginning proclaim: “The strange, nightmarish, monstrous, utterly incredible yet true story of his life.” Lenica styled his intellectual comic strip with engraved backgrounds and decors similar to those he used in Labirynt, while the travails of “Adam 2” resemble the predicaments of the anonymous characters in both Labirynt and A. The minimal dialogue, presented in the form of intertitles, was written by Eugène Ionesco whose Rhinoceros Lenica had previously adapted. I’ve no idea what the number 44 represents in this scenario but it’s a prevalent fixture throughout.

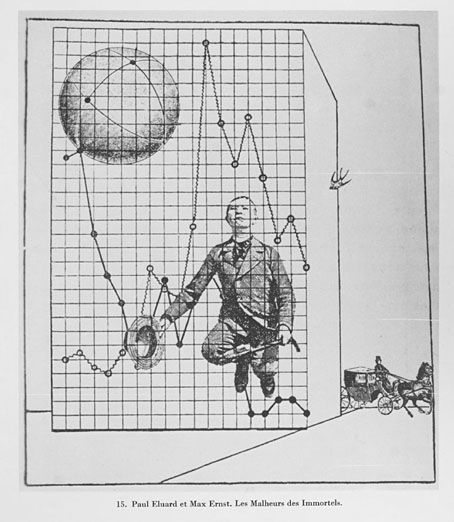

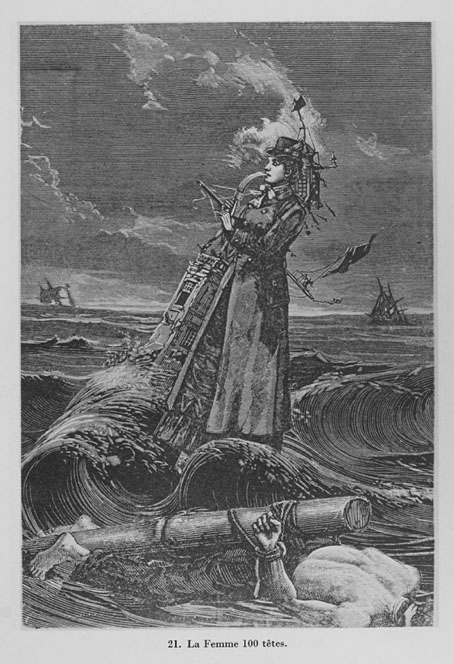

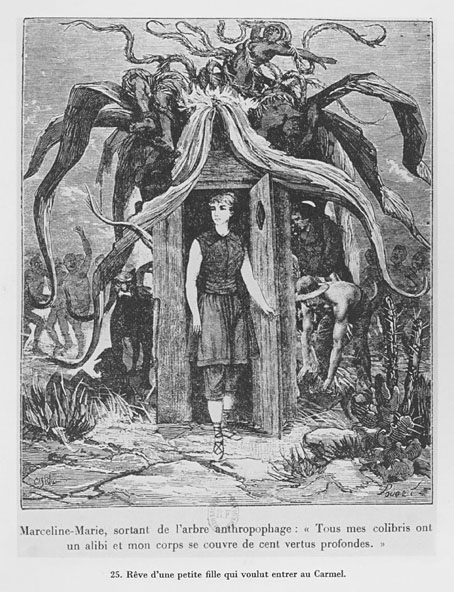

In a year in which the posts here have been preoccupied with Surrealism I ought to note that Lenica’s animated films are often a lot more “Surrealist” than much of the live-action cinema that gets tagged with the S-word. But Lenica was an animator, and animation is the poor relation of the film world, persistently overlooked and under-represented. Lenica reinforced the Surrealist tenor of his work a few years later with two animated adaptations of Jarry plays, Ubu Roi and Ubu et la Grande Gidouille, the latter being another full-length feature. I’d love to see a restored collection of his films but I’m not expecting this any time soon.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Rhinoceros by Jan Lenica

• Repulsion posters

• Dom by Walerian Borowczyk and Jan Lenica

• Labirynt by Jan Lenica