April, Works in a Garden (1614) by Jan Wildens.

The cruellest month in paintings. Snowy scenes abound for this time of year but I’ve avoided those.

Twelve Months of Flowers: April (no date) by Jacob van Huysum.

April Love (c. 1855) by Arthur Hughes.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Painting

April, Works in a Garden (1614) by Jan Wildens.

The cruellest month in paintings. Snowy scenes abound for this time of year but I’ve avoided those.

Twelve Months of Flowers: April (no date) by Jacob van Huysum.

April Love (c. 1855) by Arthur Hughes.

The Blue Girl (2013) by Sungwon.

• “Meanwhile, in her parents’ room [Max] Ernst painted aardvarks eating ants and big human hands around the windows. ‘Sexual connotations, I think,’ she says shyly.” Agnès Poirier talks to Cécile Eluard about her childhood among the Surrealists.

• “Thrilling and prophetic”: why film-maker Chris Marker‘s radical images influenced so many artists. Sukhdev Sandhu, William Gibson, Mark Romanek and Joanna Hogg on the elusive director.

• At Dangerous Minds: Throbbing Gristle live in Manchester in 1980, and Brian Butler talks about the rediscovered early print of Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising. There’s a trailer!

• From 1981: The Art of Fiction No. 69 at The Paris Review, an interview with Gabriel García Márquez. Related: Thomas Pynchon reviewed Love in the Time of Cholera in 1988.

• “Seven years ago, a stolen first edition of Borges’s early poems was returned to Argentina’s National Library. But was it the right copy?” Graciela Mochkofsky investigates.

• “What was Walter Benjamin doing with his shirt off in Ibiza?” Peter E. Gordon reviews Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life by Howard Eiland & Michael W. Jennings.

• A video by Marcel Weber for Måtinden, a track from Eric Holm’s Andøya album. Another album on the Subtext label that I helped design.

• More Ian Miller: Boing Boing has pages from his new book, The Art of Ian Miller, and there’s an interview at Sci-Fi-O-Rama.

• Outrun Europa, a free compilation of 80s-style electronic music. There’s a lot more along those lines here.

• Praise Be! Favourite religious and spiritual records chose by writers at The Quietus.

• Ralph Steadman illustrated Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1973.

• British Pathé is uploading 85,000 of its newsreel films to YouTube.

• Drawings by Lebbeus Woods at The Drawing Center, New York.

• At Pinterest: Ian Miller and Kenneth Anger.

• Lucifer Sam (1967) by Pink Floyd | The Surrealist Waltz (1967) by Pearls Before Swine | Which Dreamed It (1968) by Boeing Duveen And The Beautiful Soup

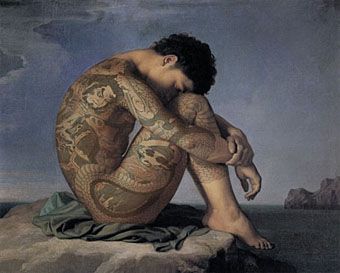

After Young Man Beside the Sea (2008) by Abe Koya.

Further examples of this most recurrent of poses continue to emerge. Abe Koya subjects Flandrin’s jeunne homme to some Japanese tattooing, one of a number of prints that give other famous artworks similar treatment.

La solitudine dei numeri due (2011) by Giuseppe Veneziano.

Giuseppe Veneziano goes the opposite route by placing a superhero in Flandrin’s seascape. Another of Veneziano’s paintings has Superman in a pieta pose; Krypton’s most famous exile had already appeared in Flandrin’s setting some years ago. (Thanks to Hans for the tip!)

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The recurrent pose archive

A Study, in March (1855) by John William Inchbold.

The windy, vernal, and ill-omened month in paintings. February by contrast was very under-represented; the approach of spring evidently gives artists a creative lift.

The March Marigold (1870) by Edward Burne-Jones.

March Sun, Pontoise (1875) by Camille Pissaro.

The Ides of March (1883) by Edward John Poynter.

Soane’s Bank of England as a Ruin (1830) by Joseph Gandy.

Joseph Gandy’s painting of the Bank of England does indeed show the building as a ruin but the painting was also intended to show the architectural layout of the place, hence the intact quarters in the lower left. The architect, John Soane, was a friend of Gandy’s, and owned the painting which usually hangs in the Soane Museum, one of my favourite places in London. Gandy’s painting is currently on display at Tate Britain as part of a new exhibition, Ruin Lust, which also features some other favourites of mine including John Martin’s The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822), and Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), a work which really needs to be seen in situ. Soane’s Bank of England, incidentally, had a less Romantic ending when it was demolished in the 20th century to make way for a newer building.

The New Zealander (1872) by Gustave Doré.

Also included in the exhibition is Gustave Doré’s surprising view of London in the distant future, the last plate in London: A Pilgrimage (1872). Visitors to Italy and Greece in the 18th and 19th century were fascinated by the idea that a city with the former splendour of Rome could have been reduced to a handful of marble ruins. This prompted the obvious thought that equally splendid cities such as London—in Doré’s time the most populous city in the world—would themselves be reduced to ruin one day. Doré’s picture illustrates a fleeting reference in Blanchard Jerrold’s text to a passage by Thomas Babington Macaulay concerning the longevity of the Roman Catholic Church. At the end of a lengthy paragraph Macaulay writes:

And she [the Church] may still exist in undiminished vigour when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul’s.

I hadn’t traced this quote before but can see now that Doré was evidently familiar with it since he’s given his future New Zealander a sketch book. It’s typical of Doré to expand on a tiny detail in this way. There are plenty of recent views of London in ruins but this is a rare example from an earlier century. If anyone knows of any others then please leave a comment.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mérigot’s Ruins of Rome

• Pleasure of Ruins

• Vedute di Roma