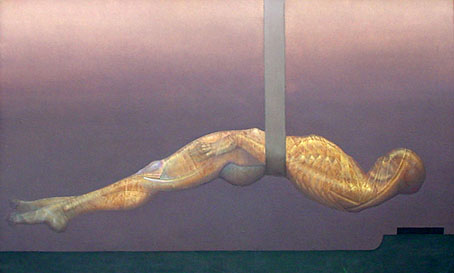

Voyageur IV (1995).

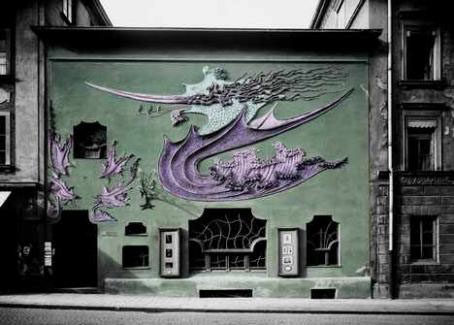

Born in Paris in 1941, he confesses to being largely “…self-taught. I was always at the Louvre, staring like crazy at the pictures there, fascinated by ‘how it’s done’.” … (Leonor) Fini’s works from the 60s influenced, to a degree, the young Henricot. Depicted in a hieratic style with underlying geometrical forms, her graceful elongated figures seem to exist in timeless spaces that are dark and densely atmospheric. Henricot’s earliest figures also have this graceful quality, but were more stylized and cybernetic, with ergonomic designs on their metallic skins. Sometimes they remained mere torsos, lacking hands to grasp or feet to stand. (More.)

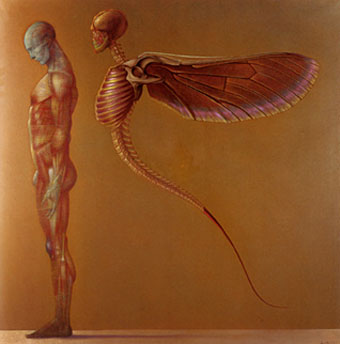

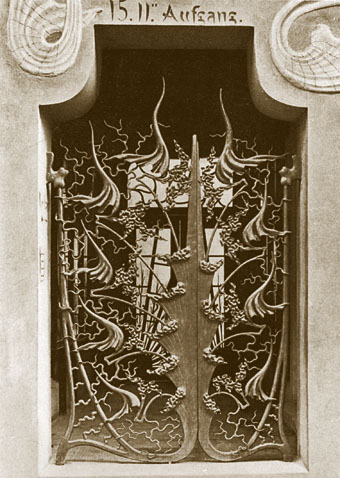

No title or date.

No title or date.

• Peinture Visionnaire: Michel Henricot at ArtsLivres

• BernArt gallery page

• CFM gallery page

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Surrealist women