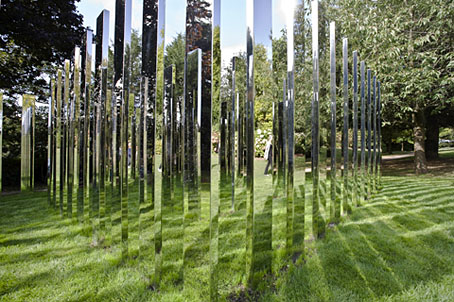

Durham Cathedral as it appeared this weekend as a part of the four-day Lumiere art event which illuminated the cathedral’s already spectacular location with projections and light installations. Flickr has a wide selection of photos documenting the various stages of the event.

The fluorescent bulbs on the banks of the Wear would have dazzled even Dan Flavin, the American founding father of light art. Durham’s river was a riot of neon and sci-fi lasers. What Flavin would make of this display is another matter. Light art has come a long way since the industrial minimalism that saw syncopations of strip bulbs arranged in white gallery spaces. Contemporary artists are using low-emission technology to produce site-specific work on a grand scale. Unlike the postwar modernists, their work has a social function: to transform cities. They are engineers of public space and sculptors of civic identity.

Durham’s Lumiere is part of a growing international movement. The organisers, Helen Marriage and Nicky Webb from the London-based events company Artichoke, loosely modelled the event on an annual Fête des Lumières in Lyon (5–8 December), a festival that hosts 80 light installations and attracts over 4 million tourists every year. (More.)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Tetragram for Enlargement

• Eno’s Luminous Opera House panorama

• The art of Rune Guneriussen

• Lightmark

• Giant Lantern Festival

• Maximum Silence by Giancarlo Neri

• Volume at the V&A