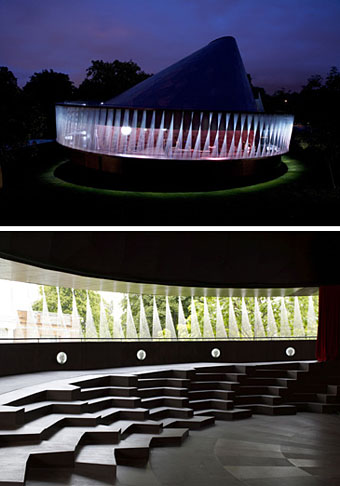

The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2007, designed by the internationally acclaimed artist Olafur Eliasson and the award-winning Norwegian architect Kjetil Thorsen, of the architectural practice Snøhetta, is now open to the public and will remain on site until November 2007.

The Pavilion acts as a “laboratory” every Friday night with artists, architects, academics and scientists leading a series of public experiments. The programme, conceived by Eliasson and Thorsen with the Serpentine, will begin in September and culminate in an extraordinary, two-part, 48-hour marathon laboratory event exploring the architecture of the senses.

The Serpentine Pavilion 2007 is a spectacular and dynamic building. The timber-clad structure resembles a spinning top and brings a dramatic vertical dimension to the more usual single level Pavilion. A wide spiralling ramp makes two complete turns, ascending from the Gallery’s lawn to the seating area and continues upwards, culminating at the highest point in a view across Kensington Gardens and down into the chamber below.

Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson is based in Berlin where he established Studio Olafur Eliasson, a laboratory for spatial research. His work explores the relationship between individuals and their surroundings, as experienced in his awe-inspiring large-scale installation The weather project, 2003, at Tate Modern. Publisher of a new magazine that melds artistic and architectural experimentation, Eliasson is currently involved in numerous architectural projects such as the Icelandic National Concert and Conference Centre in Reykjavik (design of the building envelope).

He is collaborating with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., on a project that reconsiders the Museum’s communicative potential, and he recently won the competition for a large rooftop extension at ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Denmark.

Kjetil Thorsen is co-founder of Snøhetta, one of Scandinavia’s leading architectural practices, with offices in Oslo and New York. The Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Egypt, 1995–2001, is the commission that brought Snøhetta to international acclaim. Thorsen is responsible for the design of award-winning public buildings globally, and has collaborated with Eliasson several times, including The Opera House, Olso, currently under construction. He is a founder of Galleri Rom, Oslo, which focuses on the intersection of architecture and art, and is a member of the Norwegian Architectural Association (NAL) and the American Institute of Architects (AIA). He is also Professor at the Institute for Experimental Studies in Architecture at the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The London Oasis

• New Olafur Eliasson