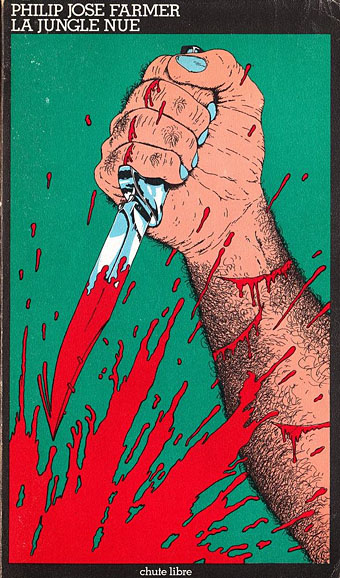

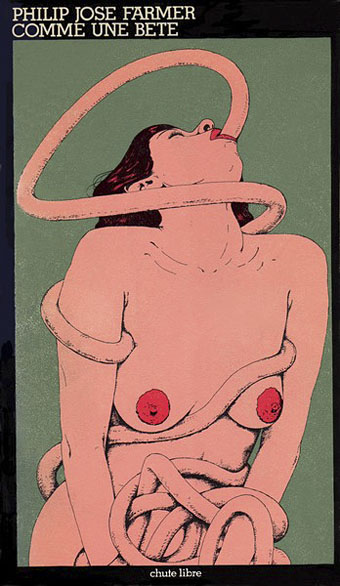

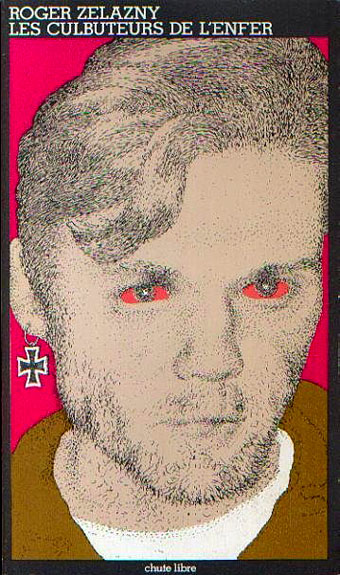

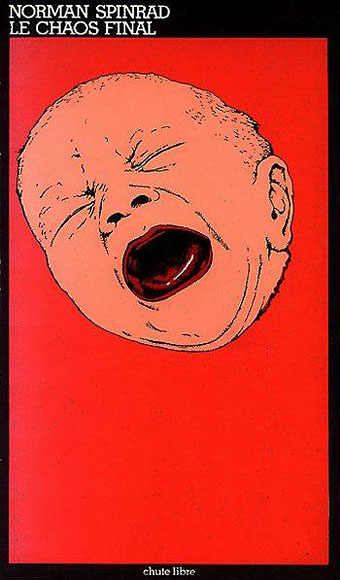

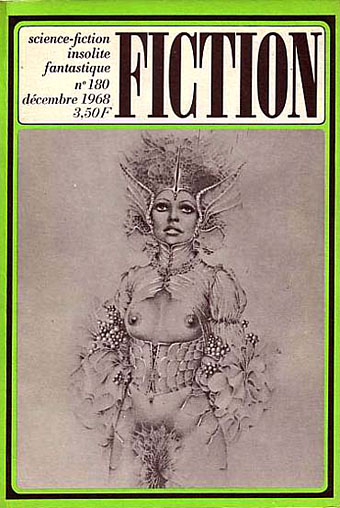

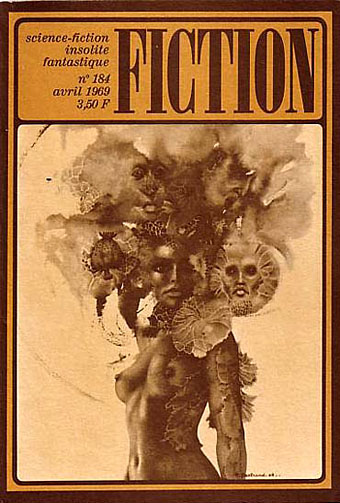

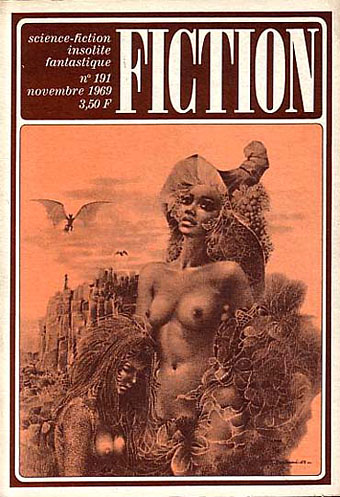

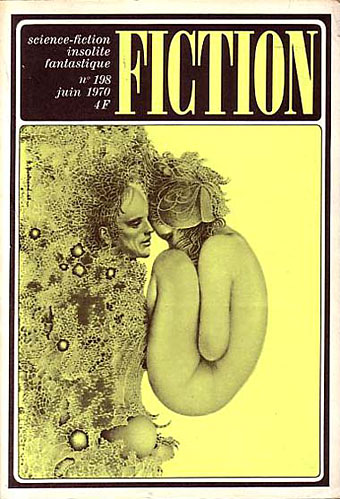

Work by the elusive French artist Raymond Bertrand has appeared here before although the art continues to be more visible (if obscure) than the man himself. Bertrand’s most famous drawings are the naked women that appeared on the cover of issue 28 of Oz magazine, the notorious School Kids Issue, but I don’t think he was credited for the usage and his name is never mentioned when the magazine is discussed. Looking for information about the Chute Libre books at French SF site Noosfere led me to an entry for Bertrand’s work. The list doesn’t include any of the book collections of his drawings but does have these magazine covers which feature some pieces I hadn’t seen before.

Fiction was the leading French SF magazine, and sported a fascinating range of cover art especially from the mid-60s on. Artists at that time included Philippe Druillet and Philippe Caza, both of whom would become big names in the comics world a few years later. Galaxie was the French edition of American magazine Galaxy, and featured unique material among its translations of Anglophone works. Being French, there’s a greater amount of flesh on display than you’d find on magazine covers in the US and UK; some of this is as salacious as anything else from the period although at least one of the artists drawing naked females was a woman, Sophie Busson. Naked females emerging from—or being absorbed by—strange vegetation, polyps or aquatic organisms were Bertrand’s métier so that’s mostly what one finds here. Few of the covers seem to relate to the magazine’s contents, the artists appear to have been free to draw what they liked; in the case of Druillet that means his usual Lovecraftian architecture. An exception is issue 198 of Fiction which has an article about Bertrand’s work by Jacques Chambon: Raymond Bertrand ou de l’amour de l’art à l’art de l’amour. I’m hoping now that someone might be good enough to translate that piece for us lazy Anglophones.

And speaking of former Oz artists, Renaud Leon left a message recently with news that YouTube now has a channel featuring many examples of Jim Leon’s remarkable paintings.

Continue reading “Raymond Bertrand’s science fiction covers”