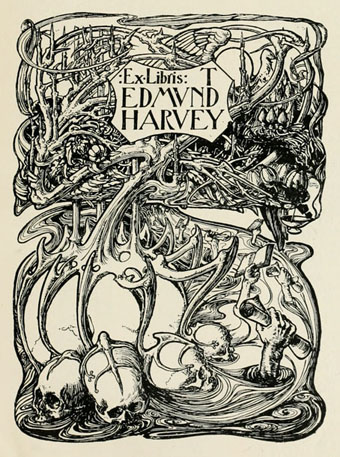

Cartouche with Macabre Symbols and a Hairy Skull (no date).

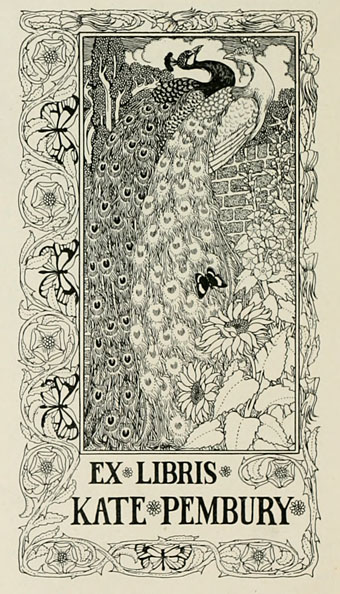

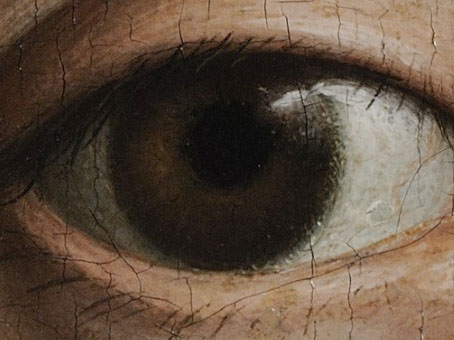

Some macabre things for a macabre month. Jacopo Ligozzi was a Mannerist artist, and the date of his birth here is the most commonly cited one, some sources give later years. The excesses of Mannerism—distorted figures, sensational subject matter, grotesquery in general—used to be regarded with suspicion if not downright hostility by the guardians of good taste who write art history books. Peter & Linda Murray’s frequently snotty Dictionary of Art and Artists (1959) describes the style as being “best adapted to neurotic artists”, then goes on to list a few allegedly neurotic types, none of whom are Ligozzi. Judging by these examples, the artist had a thing for memento mori since many of the examples of his work online are grotesque cartouches or scenes of a rampaging Death. The last picture here showing a curious peacock boat is credited to Remigio Cantagallina and was discovered at the rather wonderful Frequent Peacock (now relocated here), another site which saves me the trouble of searching out further peacock pictures.

Thanks to Wunderkammer for the Ligozzi tip!