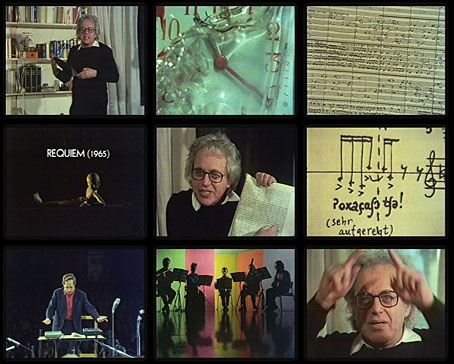

The title translates as “self-portrait of an unknown” although “unknown man” would be better English. The phrase is a curious one to apply to Jean Cocteau, an artist (or “poet”, to use his favourite epithet) who was known for his creative work from a very early age. Director Edgardo Cozarinsky uses Cocteau’s own narration from a collection of documentary films to chart the evolution of a polymathic public life, following the progress of Cocteau’s art from the poetry of his youth (which the older man deemed “absurd”), to his involvement with the Ballets Russes, his films and plays, and his later flourishing as a painter of murals like those in the Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer.

In one of the later scenes Cocteau is shown talking to a wax figure of himself, describing the dummy as the one who goes out into the world to receive the plaudits and brickbats accorded to “Jean Cocteau” while the real Cocteau stays quietly at home in the south of France. The quotidian Cocteau would be the “unknown” in this respect; there’s no mention of his life with Jean Marais, for example, but I’m happy enough to spend an hour listening to him talking about his art. The reference to brickbats is a reminder that in France he was often reviled during his lifetime, regarded as a dilettante and a fraud. This was especially the case in André Breton’s Surrealist circle where those who wanted to avoid excommunication had to support the master’s lasting animus against the unknown poet.

A pair of Surrealist untouchables, 1953.

Given this, I was amused to see a brief shot of Cocteau signing a wall with the most notorious member of Breton’s long list of outcasts, Salvador Dalí. Cocteau was friends with Dalí in later years, and in one of the film clips mentions the painter introducing him to the concept of “phoenixology” or the revival of dead matter. Dalí had biological science and his own immortality in mind but for Cocteau the idea becomes a metaphor for the artistic process, something we see in Le Testament d’Orphée and La Villa Santa Sospir when he pieces together the petals of disassembled flowers.

I was watching a copy of Cozarinsky’s film which may be downloaded at Ubuweb. The narration is in French throughout but English subtitles are available here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Orphée posters

• Cocteau and Lovecraft

• Cocteau drawings

• Querelle de Brest

• Halsman and Cocteau

• La Belle et la Bête posters

• The writhing on the wall

• Le livre blanc by Jean Cocteau

• Cocteau’s sword

• Cristalophonics: searching for the Cocteau sound

• Cocteau at the Louvre des Antiquaires

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau