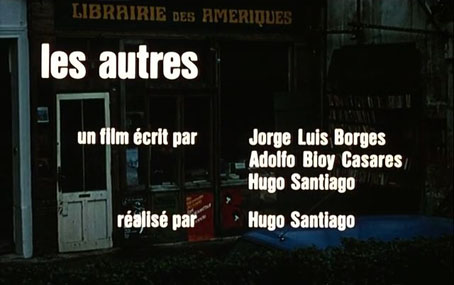

The Others (1974) is the second of the feature-length collaborations directed by Hugo Santiago from screenplays developed with Adolfo Bioy Casares and Jorge Luis Borges. The film was produced in Paris with a French cast, together with two of Santiago’s collaborators from Invasion: cinematographer Ricardo Aronovich and composer Edgardo Cantón. The association of Borges with this one seems to have been little more than providing a very simple idea which I won’t reveal here since doing so would give away the entire story. In later years Borges was dismissive about film adaptations derived from his works but this one is still creditably Borgesian even if it isn’t as satisfying as Invasion.

The story concerns one Roger Spinoza (Patrice Dally), a middle-aged man with a very Borges-like name who runs a bookshop, Librairie des Ameriques, in the centre of Paris. The abrupt and apparently meaningless suicide of Spinoza’s son, Mathieu (Bruno Devoldère), precipitates for the bookseller a personal and possibly metaphysical crisis which prompts him to visit his son’s friends in the hope of discovering an explanation for the tragedy. Spinoza’s visits to Mathieu’s girlfriend, Valérie (Noëlle Chatelet), develop into a romantic relationship which brings him into conflict with Moreau (Daniel Vignat), a lawyer who was Mathieu’s rival for Valérie’s affections. (Valérie works at an astronomical observatory which gives her a natural affinity with Spinoza, a man who shares a name with the Dutch philosopher who supported himself by grinding lenses for Christiaan Huygens’ telescopes.) These events are complicated and rendered mysterious by the presence of “the others”, a number of strange men who individually shadow Spinoza’s investigations while harassing Mathieu’s friends and acquaintances. The actions and identities of the men remain inexplicable until the very end when an explanation—the original idea from Borges—makes everything clear. The philosophical side of Borges’ suggestion is absent, however, which makes the explanation seem both glib and fantastic, but it has the effect of presenting all the events of the past two hours in a very different light.

So why is this not as satisfying as Invasion? In part because Santiago sporadically interrupts his narrative with brief scenes that show the film itself in the process of creation. These are continuations of a 10-minute prologue of outtakes, scene setups, rehearsals, Santiago’s asides to the camera, and so on, all of which are differentiated from the film proper by the cold blue/green cast you get from film footage that hasn’t been filtered for daylight. There was a lot of this kind of Brechtian fourth-wall breaking going on during the 1970s, usually without achieving very much. Santiago’s story is confusing enough without being further fragmented by distracting interruptions. Another distraction is the Edgardo Cantón score which follows Invasion in its use of musique concrète as well as more conventional orchestral scoring. But where the Invasion soundtrack complemented the action the score here works against the film, especially when the sounds and snatches of music are more abrasive than they were previously. I can put up with all manner of directorial eccentricities but this example tested my patience. It’s hard to see why a story such as this would warrant a Brechtian treatment, which suggests that the distractions are more of a result of the director’s lack of faith in his screenplay.

Bioy Casares, Borges and Santiago.

Flaws aside, The Others isn’t without attractions for Borges readers. The film is truer to the spirit of Borges than many of the adaptations of the author’s stories: mirrors abound, and play a significant part in the narrative, while Borges’ words are present in the Grove Press edition of Ficciones seen on a shelf in the bookshop, and in the character of Valérie who informs Spinoza that she was born in Buenos Aires. After the pair have spent the night together Valérie recites in Spanish the Borges poem Spinoza. “Do you know that poem,” she asks. “Yes,” says Spinoza, “it’s from a fellow librarian.” The librarian himself is seen at the very beginning of the film during the production prologue, talking (silently) to Santiago and Adolfo Bioy Casares.

In a note about Death and the Compass, Borges said that most stories should stand or fall by their general atmosphere rather than their plot. The Others would have succeeded very well on this level if not for its flaws; the events are persistently intriguing and the streets of Paris are effortlessly photogenic, a sombre city captured at angles and cropped views by Aronovich’s camera. Three years later Aronovich was photographing another series of enigmas for Alain Resnais in Providence. Like the Resnais film, The Others has been unavailable for far too long but may now be viewed with English subtitles here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Invasion revisited

• Goodfellow and Borges

• The Rejected Sorcerer

• The Immortal by Jorge Luis Borges

• Borges on Ulysses

• Borges in the firing line

• La Bibliothèque de Babel

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• The Library of Babel by Érik Desmazières

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance

I’ve been enjoying these posts about Borges and film since I knew nothing about it. It’s hard to imagine a successful adaptation of a Borges story not that it couldn’t be done I suppose. Borges’ work contains the literary elements most difficult to translate into a visual medium.

There is something attractive about the plot of The Others. A man who tries to connect with his dead son by entering into his life and as it were continuing his life as a surrogate. Perhaps this movie is ripe for a remake. I’ve always thought the best remakes were of flawed movies. Hollywood remakes successful movies which always seems strange to me (although their motivation – a built in audience – is obvious.)

Yes I hate “metafiction” in all its guises. As Johan Huizinga points out in Homo Ludens, the audience wants to participate in the magic trick; wants to be “fooled”. If the magician pauses and explains the trick he simply doesn’t understand the game he’s playing and betrays the compact with his audience.

I can quote the very line that made me a lifelong Borges fan. That still gives me the strangest feeling. From The Library of Babel in Labyrinths, translated by James E Irby.

-Once I am dead, there will be no lack of pious hands to throw me over the railing; my grave will be the fathomless air; my body will sink endlessly and decay and dissolve in the wind generated by the fall, which is infinite.

Yes, a remake of this one might be a good idea although such a thing would have to avoid the temptation to explain events any more than necessary.

Borges himself wasn’t above commenting on his own work but there’s usually a good reason for it. At the end of Averroes Search Averroes and his surroundings disappear, “as if fulminated by an invisible fire”, to be replaced by Borges himself in the final paragraph who then explains why he wrote the story. I’m not completely averse to metafiction but for it to work successfully in a feature film it requires a very skilled practitioner. Charlie Kaufmann is one of these, especially with Adaptation and Synecdoche, New York. A lot of the Brechtian attitude, post-Brecht, seems impelled by a patronising view of the audience: “These people are easily beguiled by fairy tales, they need to be shocked out of their complacency and reminded that this is a work of fiction!”, etc, etc.