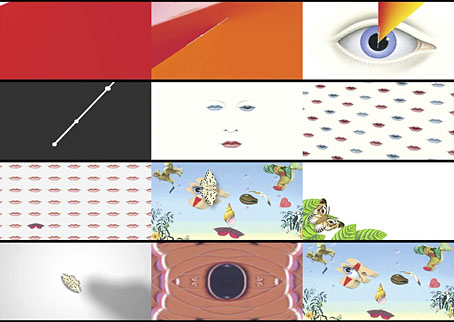

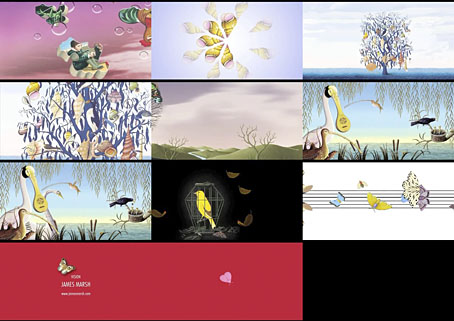

In which artist James Marsh animates the paintings of his which appear on Talk Talk’s album covers. This is a promo film for Spirit Of Talk Talk, a cover version collection released last year on Fierce Panda. Thanks to Thom for the tip!

Month: January 2013

Maze and labyrinth panoramas

Parc del Laberint d’Horta, Barcelona by Valentin Arfire.

Continuing the maze and labyrinth theme, a selection of panoramas at 360Cities. Panoramic photography helps when viewing these constructions at a distance, especially when the camera is centrally positioned. The selection may be small but it shows how universal the urge is to build these things, with examples from Europe, the heart of Russia (where we learn that labyrinths are called “Babylons”) and China. Some of the pages have links to additional views. There’s a plan of the Parc del Laberint d’Horta hedge maze at Wikipedia.

Granite Maze, Kirchenlamitz, Bavaria by Martin Hertel.

Centre of the labyrinth (4 of 6), Castle Weldam, Netherlands by Jan Mulder.

“Vavilon” (Babylon) labyrinth, Kandalaksha District, Murmansk by Andrei Kuznetcov.

Labyrinth at the Uithof, the Hague by Marco den Herder.

Beijing Old Summer Palace 4, Labyrinth in Yuanmingyuan by Yunzen Liu.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The panoramas archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mazes and labyrinths

• Labyrinths

• Jeppe Hein’s mirror labyrinth

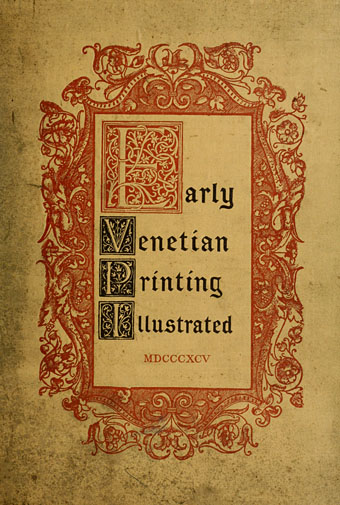

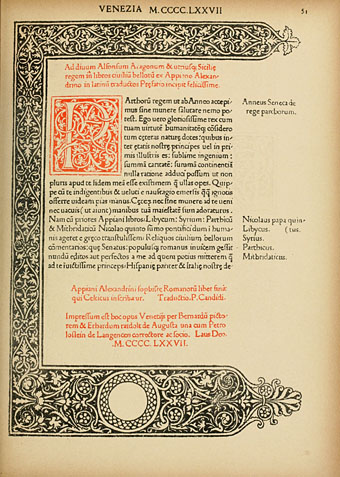

Early Venetian Printing Illustrated

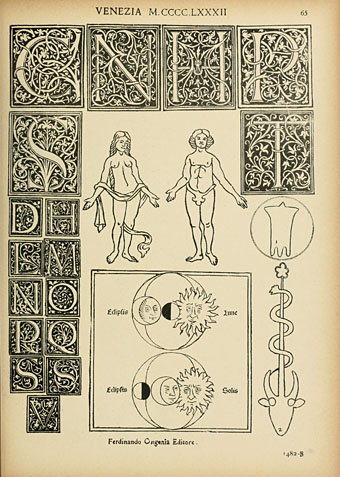

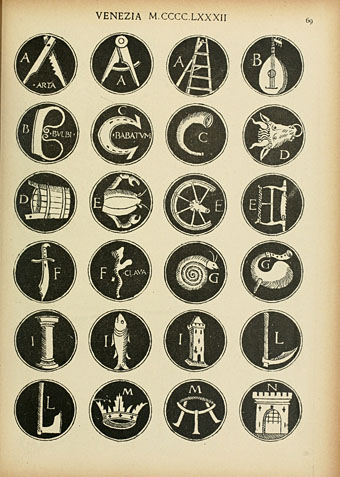

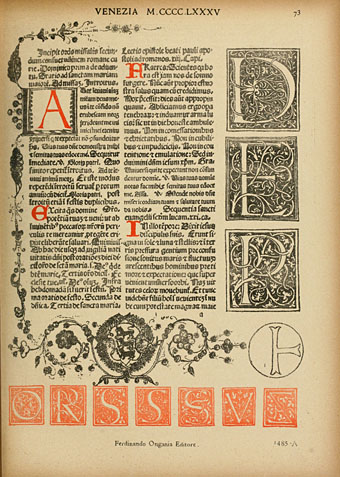

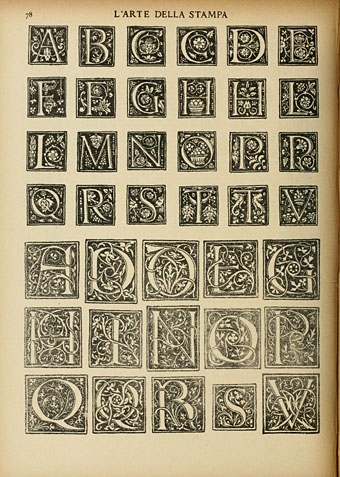

THE HISTORY OF THE ART OF PRINTING, studied in its most valuable examples, shows clearly how the work of the early printers took, from the very commencement, a national and also a personal character. These are recognised by the modern student in the special forms of type which they employed, and in the character of the ornaments and vignettes with which they decorated their editions; which thus formed, as it were, a species of art-work countersigned by the particular conditions of date, place and genius. Every early edition, with its various characteristics of size, type and ornamentation, is thus, not merely a trade specimen, but also an historical and artistic document, agreeing in character with the arts of design, the social customs and the literary tastes in vogue at the period in question. The early German printing, with its rigid and angular types and its Gothic ornaments, is perfectly suited to an age and to a country still mediaeval, and the Italic type of Aldus Manutius is equally suited to the calm and elegant classical character of the art of the Renaissance. Volumes with wide margins, large type and eccentric engravings tell of the pompous magnificence which found favour in the seventeenth century and of which that century has left so many specimens in our libraries.

Thus Ferdinando Ongania in Early Venetian Printing Illustrated, a tremendous collection of early print decorations, ornamental capitals, engraved illustrations and printers’ emblems. Ongania’s book was published in 1895, and once again the late 19th century is shown to be a fruitful period for this kind of early graphic history. A frequent frustration when searching through the thousands of scanned volumes at the Internet Archive is to locate plenty of books from a given period only to find that the illustrations or decorative material are sparse. Ongania’s collection dispenses with the text of the original volumes to present over 230 pages of graphics. Browse it here or download it here.

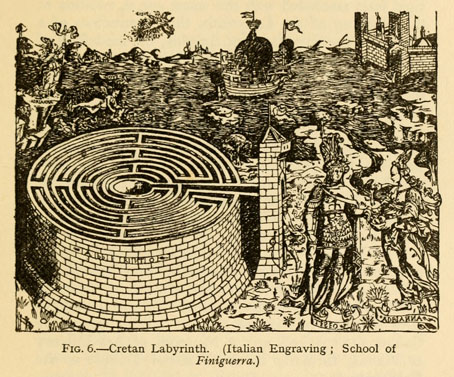

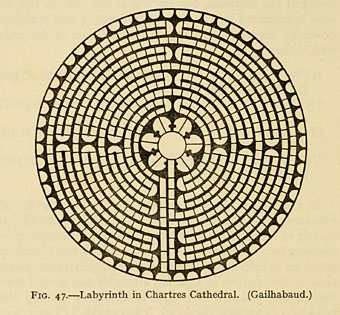

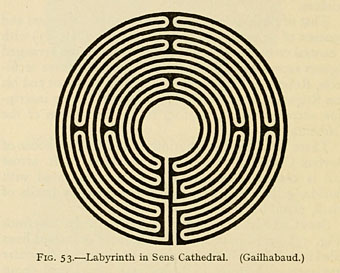

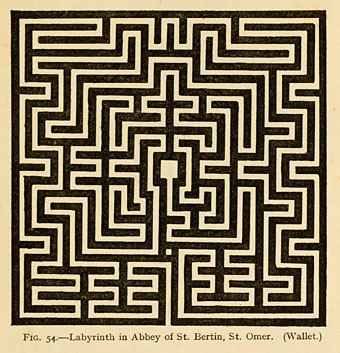

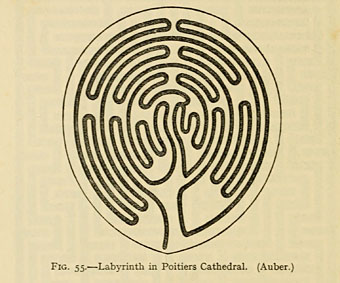

Mazes and labyrinths

This book, Mazes and Labyrinths: A General Account of their History and Developments (1922) by William Henry Matthews, would have been very useful a couple of years ago when I was working on the cover design for Mike Shevdon’s The Road to Bedlam and required a labyrinth diagram. The one I used, a plan of Julian’s Bower in Alkborough, Lincolnshire, can be found below. I’ve had a lifelong interest in mazes and labyrinths so this book is fascinating beyond any temporary work requirements. Matthews’ study of the form features many diagrams going back to the legendary Cretan labyrinth and the constructions of the Ancient Egyptians. Closer to home there are depictions of the designs which flourished during the great era of landscape gardening in the 18th century, and photographs of some of Britain’s remaining turf mazes. The book may be browsed here or downloaded here.

Nigel Kneale’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

If I’d been more diligent I would have posted this yesterday which happened to be the UK’s first George Orwell Day. The Quatermass Experiment and this adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four are the two outstanding dramas from the very early days of British television. Both were written by Nigel Kneale and directed by Rudolph Cartier, an expatriate Austrian who brought to the small screen skills honed at the UFA studios before the war. The Quatermass Experiment was the first major collaboration between the pair after which they adapted Wuthering Heights. Nineteen Eighty-Four followed, a production that was screened twice in November 1954, and which caused considerable controversy at the time on account of its oppressive atmosphere and the scenes of Winston Smith’s torture.

Kneale’s drama, which was performed live in the studio on both occasions, looks primitive compared to everything that’s followed but in many ways I prefer this adaptation to Michael Radford’s glossier feature film. For a start it has a great cast: Peter Cushing plays Winston Smith, Yvonne Mitchell is Julia, Donald Pleasence is Syme, and André Morell (who later played Professor Quatermass in the BBC’s Quatermass and the Pit) is O’Brien. Also among the cast there’s Wilfrid Brambell in two minor roles, one of them a precursor of the crusty old man he’d spend the rest of his life portraying. Neither Cushing nor Pleasence were known as film actors at this time; both would no doubt have been surprised to be told that their subsequent careers would involve a great deal of horror and science fiction.

Cartier and Kneale didn’t have the budget to compete with feature films but for once the claustrophobic nature of a studio production works in the favour of a drama where there’s little intimacy or privacy. With the exception of a few filmed inserts almost everything is close shots. As the story grows more desperate so the shadows close in, until the final scenes are all spotlit faces in darkened rooms. The power of Cushing’s performance still resonates today, and gives an idea of how shocking this must have been to a home audience expecting little more than light entertainment on a Sunday evening. The YouTube copy is the entire 107-minute film, and is worth a watch if only to see Donald Pleasence when he had an almost complete head of hair.

• From 2009: Robert McCrum on The masterpiece that killed George Orwell.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Stone Tape