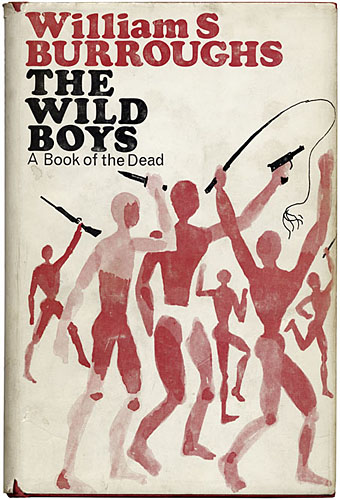

Calder & Boyars, 1972. Design by John Sewell.

This must be the first space novel, the first serious piece of science fiction—the others are entertainment.

Mary McCarthy defending The Naked Lunch in the New York Review of Books, June, 1963.

Mary McCarthy’s view—echoed a year later by Michael Moorcock and JG Ballard in the pages of New Worlds magazine—has never been popular or even particularly acceptable. William Burroughs gets touted as an sf writer by other writers, and John Clute gives him an entry in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, but Burroughs’ sf scenarios are guaranteed to offend those readers who prefer their narratives presented in a neat, linear form with detailed explanations of How The Future Would Actually Work, or the physics behind some piece of imaginary technology. The books which immediately follow The Naked Lunch—The Soft Machine, The Ticket that Exploded, and Nova Express—all feature sf scenes or ideas. The latter was deemed sufficiently generic to prompt Panther Books in the UK to publish it three times as “Panther Science Fiction” although given the severe criticism that Moorcock sustained for trying to broaden the horizons of readers in the late 60s I don’t expect sales were encouraging.

The Wild Boys, published in 1971 (1972 in the UK), was Burroughs’ first novel after Nova Express, and his first book of fresh material after mining the stack of writing that birthed The Naked Lunch and the titles which followed. The novel is subtitled A Book of the Dead (as in the Egyptian or Tibetan Books of the Dead), and is certainly science fiction although I’ve never seen it marketed as such or noticed any sf reader include it in a list of notable genre novels of the period. My Calder & Boyers hardback offers a précis of the fractured narrative:

The year is 1988. The Wild Boys, adolescent guerilla armies of specialized humanoids, are destroying the armies of the civilized nations and ravaging the earth. The wild boys, who began in the pre-present past as petrol gangs, dousing their victims with petrol and setting them on fire for kicks, have grown to an army, dedicated to violence. One of them is used in a cigarette commercial. He becomes a new cult figure, a demi-god responsible for great destruction, and it is left to strong man Arachnid Ben Driss to exterminate the wild boys. He slaughters them, but the battle continues underground until all civilization collapses, revealing a future of horrifying dimensions. The originality of the theme and the very special Burroughs style together make this one of the most unusual science fiction novels ever, a prophetic exploration of the future, that should quickly establish itself as one of the classics of the present time.

That’s accurate, up to a point, although like many book blurbs it misrepresents the content somewhat. It also neglects to say how funny the book is. For anyone with a black sense of humour Burroughs has always been a great comic writer, and The Wild Boys has some prime examples, not least the opening chapter, Tío Mate Smiles, which is best appreciated in the author’s own reading.

Having gone through the novel in the past week, and going through its follow-up/appendix/remix Port of Saints at the moment, a couple of things occurred to me. The first was the way The Wild Boys strongly prefigures later works like Cities of the Red Night and The Place of Dead Roads. This is a fairly obvious point but it’s one that hadn’t fully clicked until now. The Wild Boys takes the problems of repressive control systems posed in the first few novels and offers a possible solution: a homoerotic utopia/dystopia where gangs of teenage boys hide out in depopulated regions, waging war against the rest of humanity with sex, magic and a mastery of weapons, including biological and viral varieties. While doing this they are steadily mutating so they can leave behind all human concerns with nation, family, laws and written language. Cities of the Red Night was Burroughs first novel after The Wild Boys and presents a less radical proposal, ranging through time with its anarchist pirate colonies and the six cities of the title. In The Place of Dead Roads Kim Carsons has his band of outlaw cowboys, The Wild Fruits, and the book gives us the conflict between the Johnsons—those who “mind their own business”—and the Shits: lawmen, politicians, tycoons, all the usual agents of Control.

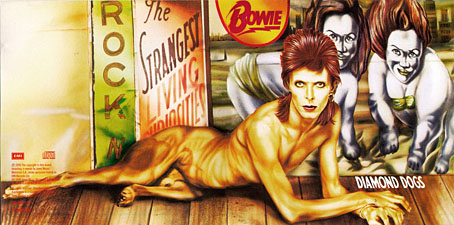

Diamond Dogs (1974). Painting by Guy Peellaert.

The more notable point about The Wild Boys is how influential the book has been. Something about the central idea captures the imagination of readers in a manner which exceeds the influence of Burroughs’ other novels even though it’s never been regarded as one of his best works. JG Ballard always described Burroughs as the first mythmaker of the 20th century; from that perspective we can see the Wild Boys idea as a potent myth of youthful rebellion and the ongoing struggles against coercion and repression.

A couple of weeks ago I noted a possible Burroughs influence with a link to the David Bowie interview from February 1974. Bowie had just finished recording his own dystopian concept album, Diamond Dogs, but at the time of the discussion with Burroughs seems to have only read Nova Express. Years later, however, we find this comment about the way the “Diamond Dogs” of his album prefigured London’s punks:

…in my mind, there was no means of transport, so they were all rolling around on these roller-skates with huge wheels on them, and they squeaked because they hadn’t been oiled properly. So there were these gangs of squeaking, roller-skating, vicious hoods, with Bowie knives and furs on, and they were all skinny because they hadn’t eaten enough, and they all had funny-coloured hair. In a way it was a precursor to the punk thing.

Roller-skates, eh?

At a long work bench in the skating rink boys tinker with tiny jet engines for their skates. They forge and grind eighteen-inch bowie knives bolting on handles of ebony and ironwoods of South America that must be worked with metal tools…

The roller-skate boys swerve down a wide palm-lined avenue into a screaming blizzard of machine-gun bullets, sun glinting on their knives and helmets, lips parted eyes blazing. They slice through a patrol snatching guns in the air.

The Wild Boys, chapter 15.

No need to give Bowie grief over this, he introduced Burroughs to a wider audience than many who followed. The first mention of Burroughs’ name that I recall was in the BBC documentary, Cracked Actor, in 1975, with its scene of Bowie demonstrating his own version of the cut-up technique.

The Wild Boys would have been an ideal influence for punks but they were too damned queer for the most part so bands named themselves after junkier works like Dead Fingers Talk. John Foxx of Ultravox has mentioned The Wild Boys as an influence, and the first Ultravox album owes much to Diamond Dogs-era Bowie, but there’s nothing specific in the lyrics beyond a general atmosphere of ambisexual weirdness and urban unease.

The next significant influence is also the most frustrating, a short film by Bruce Geduldig and Winston Tong from the mid-70s. Tong’s pre-music career as a performance artist included a piece entitled Wild Boys but since information is scant about that and the film there’s no way of knowing whether they’re connected. Tong became a member of Tuxedomoon in the late 70s, with Geduldig also joining on to produce films for their shows. The Wild Boys soundtrack appeared on a rare Tuxedomoon release Joeboy In Rotterdam/Joeboy In San Francisco in 1981 (there’s also a sample on this Biosphere track), and can now be found on a Tong solo CD, Like The Others, but the film remains elusive. If anyone has a copy, put it on YouTube, please!

(At this point I can imagine complaints if I don’t mention Duran Duran. Very well. In the 1980s I used to watch their Wild Boys video seized by a smouldering hatred, wishing fervently that the real Wild Boys would ride into the studio on their skates and chop the band into bloody chunks. Will that do? No, I never liked them.)

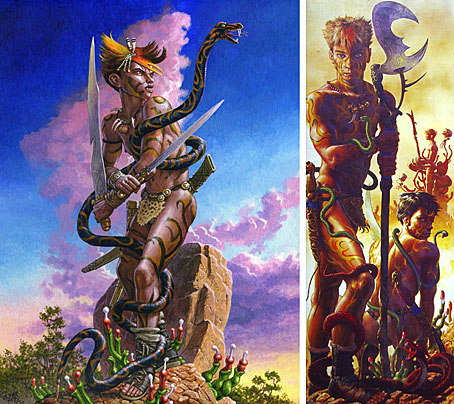

For a visual interpretation we need to look to artist Oliver Frey who had a career in the 1980s producing erotic illustrations and comic strips for gay mags under the name Zack. Given the combination of Frey/Zack’s considerable draughtsmanship and his flair for homoerotic depictions it’s a shame he hasn’t produced more work in this line. Burroughs’ books still don’t receive as much attention from gay artists as you might imagine.

Frey’s paintings date from the 1990s, and that’s where many influences that had been percolating since the 1960s start to pick up speed. Among recent Wild Boys-derived works there’s a musical piece by composer Colin Bright that mixes samples of Burroughs’ voice with percussion and saxophone. Then there’s art and magic from Elijah Burgher about whose Wild Boys 2 project he says:

WILD BOYS 2: Chapter O: An Aspiring Initiate’s Letter of Application to Know Mysteries” is part of an ongoing project, WILD BOYS 2, that I intend as a sequel to William S. Burroughs’ queer utopian novel, The Wild Boys, continuing, interpreting and critiquing some of the author’s themes and images. WILD BOYS 2 is about queer desire, magic, masculinity, fraternity, wilderness, violence, catharsis, and the creation/destruction of self.

Chaos Magician Phil Hine also traced the magical theme in 2000 with an essay entitled Zimbu Xototl Time which examines the Wild Boys’ occult techniques and attitudes:

Burrough’s description of the wild boys’ uninhibited sexuality is also interesting. Their sexuality is devoid of sentimentality & meaning; unhindered by either emotional values or a sense of transcendence.

Zimbu Xolotl Time is the wild-boy festival where the different tribes gather to meet, exchange fighting techniques and indulge in communal orgies whereby zimbus* are created. The festival has no fixed date or place – the boys converge there instinctively:

“not know for sure until two weeks before time all boy stop fuck jack off he get there hot like fire.”

Port of Saints

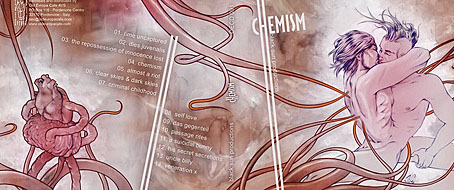

Chemism (2007) by Black Sun Productions. Design and illustration by Studio Dronio.

Black Sun Productions’ Chemism album celebrates the queer/occult trend with an album dedicated to Burroughs that’s also inspired by the novel. The title, we’re told, refers to “mutual attraction, interpenetration, and neutralisation of independent individuals which unite to form a whole.”

There are no doubt other inspirations that I’ve missed so if anyone knows of any, please leave a comment. The Wild Boys, like Burroughs’ other idealist scenarios, is a separatist utopia, a wholly masculine world where women are no longer required. Despite this, Kathy Acker said it was her favourite Burroughs novel, and in 1996 she wrote about using it as a means to think about Wild Girls. Mary McCarthy opened this post so we’ll let the last words go to Kathy:

…I see girls everywhere, girls being sexual, girls doing all and more than the boys I saw did when I used to sneak in my 20s down to the New York City wharves and hide there, in those shadows, when curling into one of the back corners of CBGBs, I would watch the endlessly skinny and black-clad legs of boys stride across a stage that was separated from me far more by gender than by space. Maybe I’m being perverse, but above all, I’m romantic and reading The Wild Boys makes me sing louder than Marianne Faithfull: “Give me more more more more…”

* Wild Boys can regenerate their dead by calling down male spirit forms which they incorporate by fucking until the spirit grows flesh. The newly-formed creatures are called Zimbus.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The William Burroughs archive

In my opinion, the Burroughs / science fiction connection is a valid point and should be addressed more often. I am sure that some pedantic sci- fi fans would disagree, but I doubt they could handle The Illuminatus! Trilogy, or Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius stuff either, or indeed anything more challenging than standard space opera.

On the other side of the cultural spectrum, there are many high- brow literary critics that canonize Burroughs without being comfortable enough to address his pulp roots. This usually leads to rather awkward assessements of his legacy, where he is praised for his use of cut- ups and his satyrical eye, but no mention is made of all the Mayan gods, flying Venusian boys, entrail- covered demons, interdimensional pirates, time travellers, giant centipedes, mugwumps and other assorted creatures that parade across the page. I always thought that both of those viewpoints were reductive and dull.

Anyway, great article John, and I hope you do a similar one for Cities Of The Red Night some time(my absolute favourite Burroughs book).

Another great WSB post. Wild Boys was the only Burroughs novel I had trouble tracking down back around 1990. Our library somehow had a copy of Port of Saints with a plain, text-only burgundy cover, which I don’t think was ever borrowed by anyone but me, but I couldn’t find or successfully order Wild Boys anywhere. Well, anywhere in Northampton. Any time I went to London I’d be too preoccupied with other matters to remember to look for it.

Dimitris: In defence of sf readers I should say that I’ve personally found people who read a lot of genre stuff to be more open-minded than the average Julian Barnes (or whoever) reader. But the genre world is still gripped by horrible insecurity about slights from literary “elites”, and (at worst) a brain-dead philistinism towards anything that attempts to make fiction writing an artistic act rather than the creation of an entertainment. I hate these artificial divides, and I’ve always done my best to ignore them, but prejudices on both sides persist.

One thing about the literary mainstream is that it copes with generic material by absorbing it; so Salman Rushdie’s first novel, Grimus, doesn’t get packaged any more as a fantasy or sf novel. The sf readership can be a lot more resistant towards things that try and bend the genre whatever the claims about being a progressive form of writing. If sf was that progressive as an art form then New Worlds would have flourished instead of being vilified and going bust. Fantasy always seems the more open-minded medium to me since the genre can easily encompass Kafka and Borges (say) without anyone blinking.

Funny you mention Illuminatus! and the Cornelius books since the former (as I recall) mentions Burroughs a couple of times while the latter were somewhat inspired by Burroughs’ example, especially in the Deep Fix story that prefigures the Cornelius work and which is dedicated to Burroughs.

Not sure how much I could write about Cities until I re-read it. Usually I need a good reason to write anything substantial like the Wild Boys post, the reason there being the amount of derived works. Cities doesn’t immediately offer the same opportunity.

3lbFlax: That copy of Port of Saints will be the same as the one I have. It doens’t seem to have been reprinted at all which is strange, some of it repeats the earlier book almost verbatim but other sections are fresh. The two books combined create a kind of Wild Boys meta-novel.

Dear Mr. Coulthart,

is this a good way to reach you?

We are preparing a comprehensive WSB exhibition scheduled to open next 23 Marchat ZKM | Karlsruhe.THE NAME IS BURROUGHS and I thought we shd be in contact abt it.

Kind regards,

Udo Breger

Hi Udo. I’ve sent you an email.