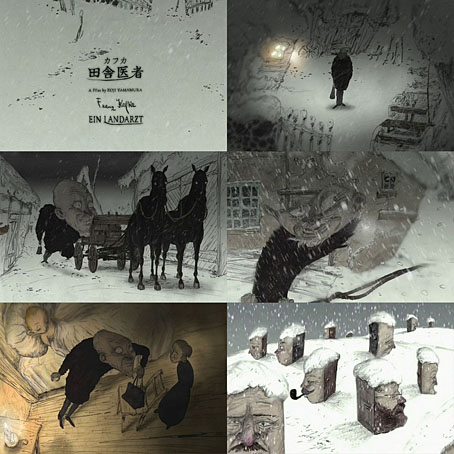

Writing about Koji Yamamura’s Parade de Satie a couple of months ago, I mentioned his adaptation of a Franz Kafka story, A Country Doctor (2007), and here it is. The Kafka adaptation was made a few years before Parade de Satie, and differs so much from the later film that you’d think they were the work of different directors. Where Parade is colourful, frivolous, and as lively as the ballet it was based upon, A Country Doctor is dark, disturbing and unpredictable. Yamamura says he chose the Kafka story from a collection of stories presented to him by a production company, only one of which appealed to him. This, coincidentally, is how Orson Welles came to direct The Trial, after producer Alexander Salkind suggested he choose a book to adapt from a list that Salkind gave him.

The events of Yamamura’s film—a country doctor is called out on a snowy night to attend to a young patient—are typical of Kafka in his shorter mode, in which absurb or dream-like situations have a tendency to slide into nightmare. Yamamura depicts the doctor’s visit in a sketchy hand-drawn style where the figures and their surroundings are continually subject to wild distortions and abrupt alterations of perspective. It’s the type of physical exaggeration that you see in the UPA cartoons of the 1950s but in those films the effect is almost always deployed for comic effect. When used in a more realistic context the distortions add to the dream-like quality of Yamamura’s film. The story is augmented by a fine score composed by Hitomi Shimizu which includes an Ondes Martenot among the instruments. If I’d have seen this in 2011 I would have included it on my list of notable Kafka film and TV adaptations.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Kafka’s machine

• The Metamorphosis of Mr Samsa, a film by Caroline Leaf

• Kafkaesque

• Screening Kafka

• Designs on Kafka

• Kafka’s porn unveiled

• A postcard from Doctor Kafka

• Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka

• Kafka and Kupka