I’m taking the biographical details about this Russian artist from a Christie’s listing, accuracy being of particular importance to auction houses. The trouble with searching for information about Nikolai Theophilaktoff is that he’s one of those Russians whose name isn’t common enough to exist in a settled non-Russian form, so you may find his drawings credited to “Nikolai Feofilaktov” or even “Nikolai Theophylactus”. Whatever the spelling of his surname, Theophilaktoff is remembered today for illustrations with a distinct Beardsley influence, which is how he came to my attention. Aubrey Beardsley only had a few years for his art to impress itself on the world but he was known in Russia during his lifetime; Sergei Diaghilev was especially enthusiastic, using his position as editor of arts journal Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) to promote Beardsley’s work after the artist’s death. A later Russian arts journal, Libra, maintained the enthusiasm, devoting an entire issue to Beardsley in 1905. It was reading about Libra that led me to Nikolai Theophilaktoff, an artist who was sufficiently beguiled by Beardsley’s drawings to embark on his own variations on the Beardsley style.

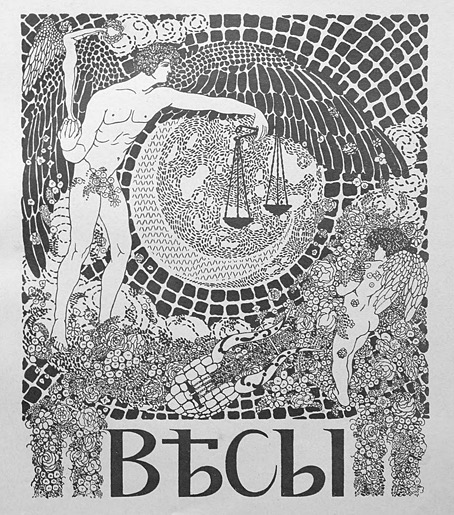

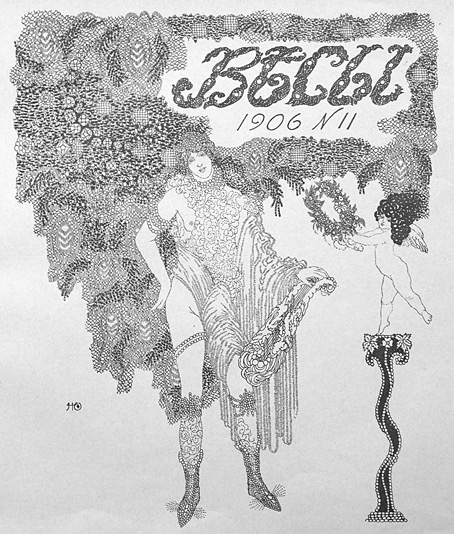

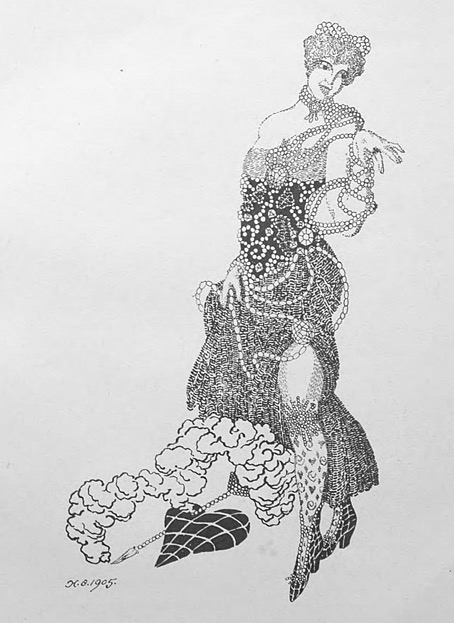

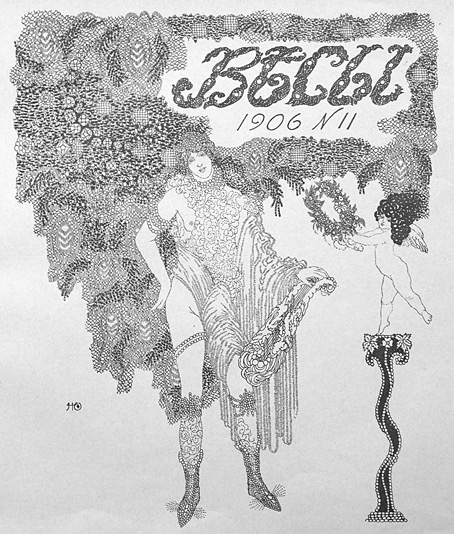

Theophilaktoff’s cover art for the Beardsley issue of Libra, November, 1905.

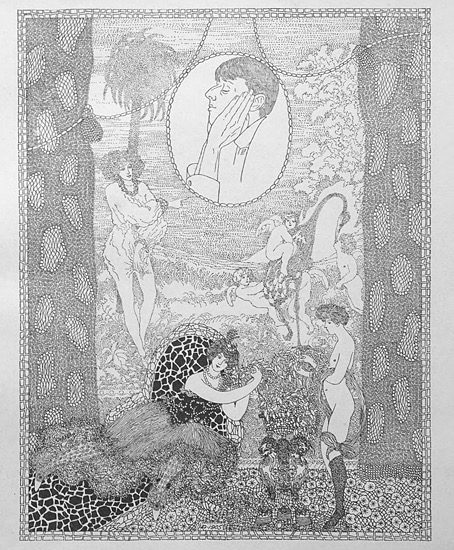

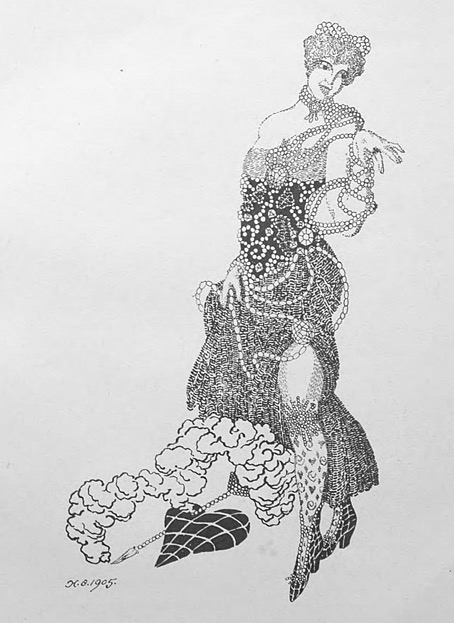

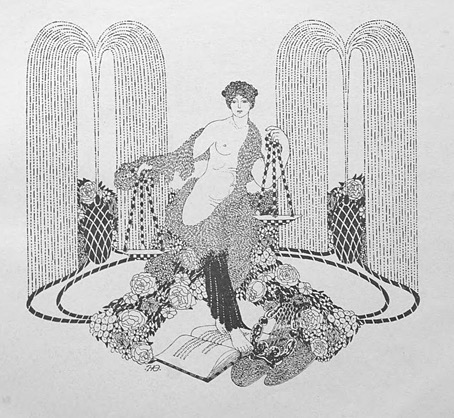

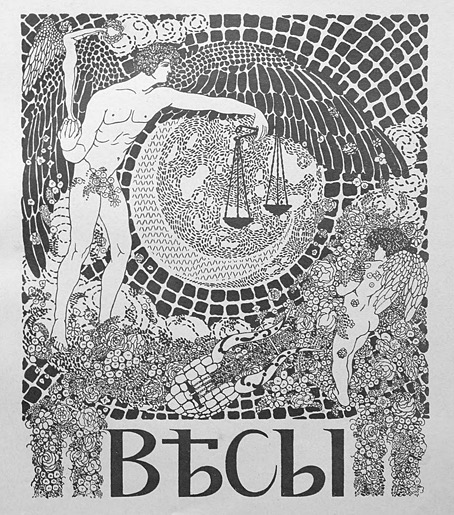

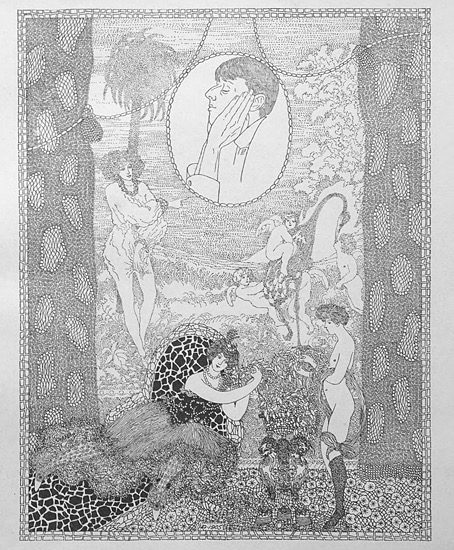

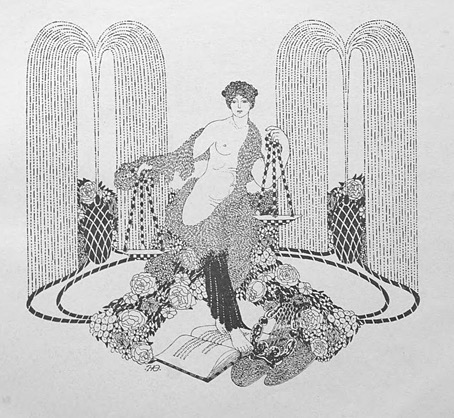

You can usually divide Beardsley’s followers into two groups: those who pick up on the striking contrasts that Beardsley created using areas of solid black against the white of the paper—Harry Clarke, Will Bradley and John Austen are good examples of this type. A second class would be those who favour the delicate, filigree style of Beardsley’s illustrations for The Rape of the Lock—Alastair (Hans Henning Voigt) and Nikolai Theophilaktoff are in this category. (Harry Clarke was also an expert filigree-ist but Clarke is really in a class of his own.) If you accept this artistic division it’s notable that the weaker artists are in the latter class. It’s easier to disguise deficiencies of figure drawing, say, with abundant stippling and decoration than it is when using nothing more than fine lines and masses of black ink. Theophilaktoff’s accomplishments are very uneven but they’re also rare examples of Beardsley’s style of Decadent art in a country that would soon have no time for such a thing at all.

Most of the pictures here are from a book, 66 Dessins (1909), which collected many of the Theophilaktoff drawings published in Libra. The pornographic drawing at the very end is a swipe from an auction listing. Also near the end are drawings for Wings (1906), a novel by Mikhail Kuzmin which is one of the first literary works to openly deal with same-sex relationships. As for Libra, I thought copies of the magazine might be impossible to find but the trusty Internet Archive has what seems to be a complete run here. Mir Iskusstva, which seems rather staid by comparison, may also be found at the Internet Archive in a series of bound volumes.

Continue reading “The art of Nikolai Petrovich Theophilaktoff, 1878–1941”