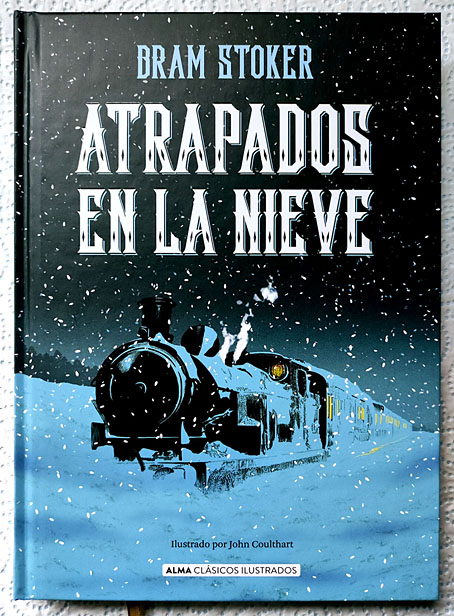

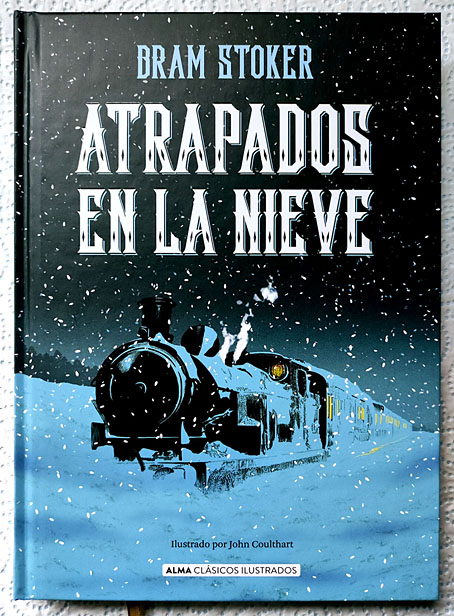

The artwork is mine; the cover design is by Lookatcia.

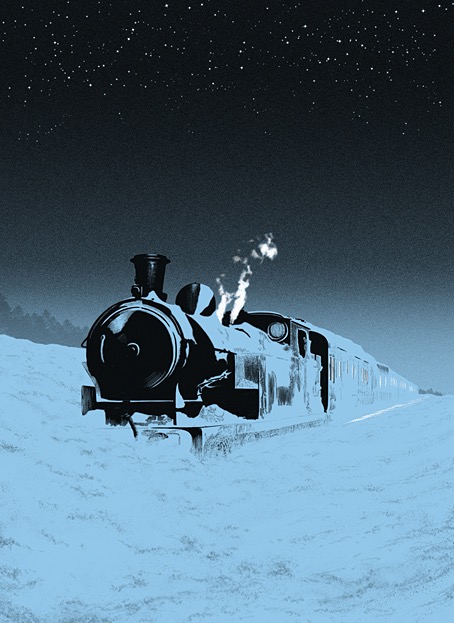

Presenting my latest book for Alma, the Spanish publisher for whom I’ve illustrated several classic novels and story collections. The new volume is my second Bram Stoker title after Dracula in 2018 which, for the sake of convenience, I’ll refer to it by its English title. Snowbound: The Record of a Theatrical Touring Party was a collection of connected stories first published in 1908, 11 years after Dracula had established Stoker’s reputation. I wouldn’t call Snowbound a bad book but if you’ve read Dracula or Stoker’s more popular short stories it’s a disappointment, with no supernatural content and little to recommend it elsewhere. The first episode introduces the framing device: a group of travelling players are marooned by heavy snow while travelling on a train through the wilds of Scotland. To pass a dark and freezing night the troupe entertain themselves by relating memorable anecdotes from their careers, anecdotes which I imagine Stoker either heard from others or experienced himself during his years working for actor-manager Henry Irving. In place of the spooky tales one might expect from such a premise we’re offered a succession of vaguely comic episodes mixed with more serious drama, with a couple of the pieces being related in very broad “Oirish” and Cockney accents. The Irish episode is especially bizarre considering that Stoker was Irish himself; it reads like the kind of thing you’d get from an English writer trotting out lazy stereotypes.

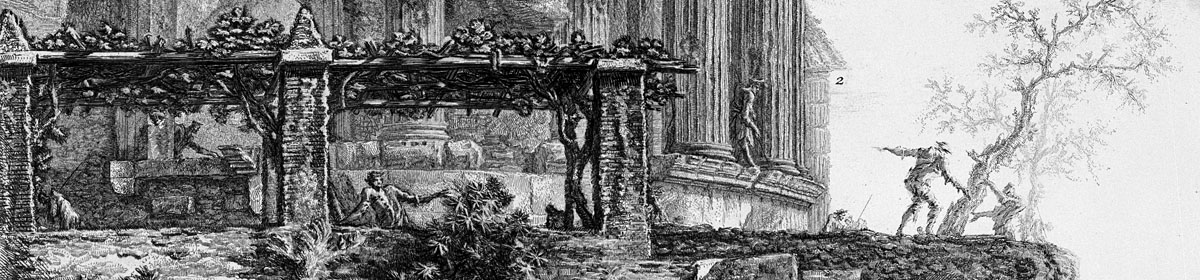

My endpapers design.

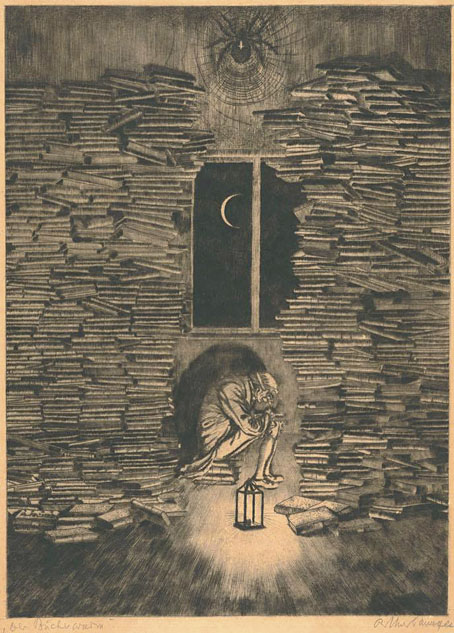

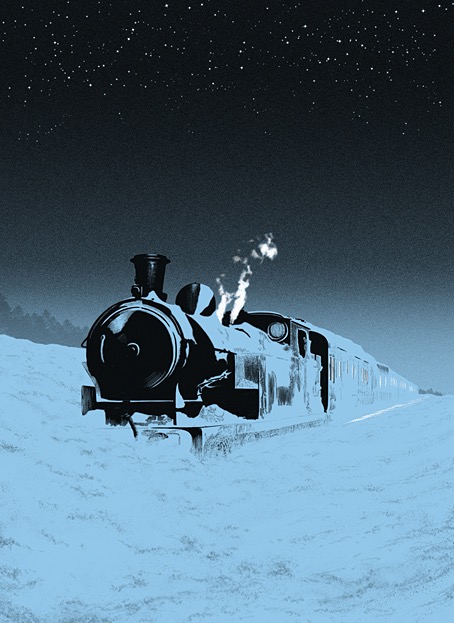

There are other flaws I could mention but I’ve undersold the book enough as it is. Snowbound has never received much attention in the past, it wasn’t even reprinted in English until 2000. In my previous books for Alma I utilised a style which combined collaged backgrounds with hand-drawn elements in order to create illustrations whose engraved appearance made them seem like products of the period in which the stories were written. More recently I’ve been moving away from this style but the success of the previous Alma editions, Frankenstein in particular, obliged me to maintain some continuity with the look I’d created for Dracula. As it turned out, several of the Snowbound illustrations are entirely hand-drawn, with engraving-like textures used in the shading. The biggest departure from the previous books is the addition of an extra ink colour to the artwork, an effect that was fun to play with when creating different lighting effects. As to the pictorial details, several of the anedotes take place in the United States, hence the presence of an American steam train with an elevated smokestack, the spelling of the word “theater” on a poster, and so on.

Having mentioned Frankenstein I ought to also mention the recent Polish edition of the novel which reprints my Alma illustrations. This is a large-format hardback from Materia, a pubisher who don’t seem to have a proper web presence outside those Meta plague sites that I never link to. The book is on sale anyway. Meanwhile, I’m currently working on another new book for Alma which will feature ten full-colour double-page illustrations. More about this later.

Continue reading “Snowbound by Bram Stoker”