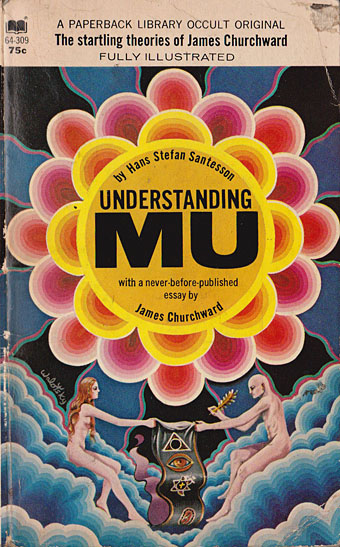

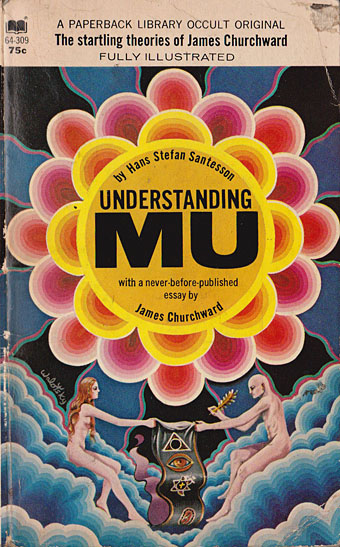

Understanding Mu (1970) by Hans Stefan Santesson. Cover art by Ron Walotsky. Via.

• “I have never believed Chariots of the Gods?—it takes faith, so what I mean is that I’ve never believed in it—but it has still held my affection for decades.” Patrick Allington on ancient aliens, unidentified aerial phenomena, and the unhinged pleasures of speculative nonfiction. I still have a stash of paperbacks in what I call “The Crank Box”, a collection of the more far-out titles that proliferated in the 1970s in the wake of the bestselling (and very egregious) Erich von Däniken. There aren’t many books about ancient astronauts or flying saucers in the box because they were so plentiful, I was always on the lookout for more outlandish volumes: lost continents, yes, but not the all-too-common Atlantis; Lemuria or Mu were more like it. So too with Hollow Earths and mysterious realms as detailed in Shambhala: Oasis of Light by Andrew Tomas, or The Lost World of Agharti: The Mystery of Vril Power by Alec MacLellan. The attraction wasn’t that any of this speculation might be true, more that these books operate as bargain-basement equivalents of the Borges conceit in which metaphysics is regarded as a branch of fantastic literature. Weird fiction by other means.

Collecting these books was a fun thing to do in the 1980s when the crank publications of the previous decade had washed up on the shelves of secondhand bookshops. The shine began to wear off in the 1990s when the emergence of the internet empowered a new breed of hucksters (and worse) pushing all of this stuff as though it was “hidden knowledge”. It’s hard to get excited about a battered paperback brimming with pseudo-science and pseudo-archaeology when similar ideas proliferate on YouTube channels catering to credulous hordes.

• Absolutely elsewhere (and linked here on a regular basis): An archive of the endlessly fascinating Absolute Elsewhere, a website created by the late RT Gault in order to present “a bibliography of visionary, occult, new age, fringe science, strange and even crackpot works published between 1945 and 1988”. The listings are accompanied by an informed, sceptical and often enlightening commentary, and also include a fair amount of weird fiction. Mr Gault had the right attitude.

• New music: Raum by Tangerine Dream, a preview of the new album, Probe 6–8, which will be released next year; new/old music: a reissue of Marine Flowers (Science Fantasy) by Akira Ito.

• “He had been honest about himself, and shockingly honest about his parents, but about his work he had spun me a tale.” Carole Angier on the elusive WG Sebald.

• At The New Criterion: Two stray notes on Moby-Dick by William Logan; on contemporary reviews of Moby-Dick and Melville’s journey on the Acushnet.

• “Perhaps what’s most extraordinary about Kollaps is that it was made at all.” Jeremy Allen on Einstürzende Neubauten’s thrilling debut album.

• At Culture.pl: a podcast about Czech film director Vera Chytilová and her masterpiece of Surrealist anarchy, Daisies.

• At Perfect Sound Forever: Part 2 of a Jon Hassell tribute which talks to friends and musical collaborators.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…William S. Burroughs The Ticket That Exploded (1962).

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine unearths a medieval recipe for gingerbread.

• Mix of the week: Death’s Other Dominion by The Ephemeral Man.

• MU-UR (2000) by Coil | Mu (2005) by Jah Wobble | Mu 1 (2015) by Acronym