Devils and Angels.

There’s been plenty of speculation over the past twenty-four hours concerning the nature of the post-mortem torments that might await Jerry Falwell now that his soul has departed its corpulent container. Various suggestions I’ve seen run the gamut from the fanciful—being buggered for eternity by purple Teletubbies—to the semi-serious—finding himself in the Third Circle of Dante’s Inferno along with the rest of the gluttons who, so Dante tells us, lie in continual hail and rain whilst eating their own excrement. For a man who spent most of his life talking shit, the latter would seem to be a fitting end.

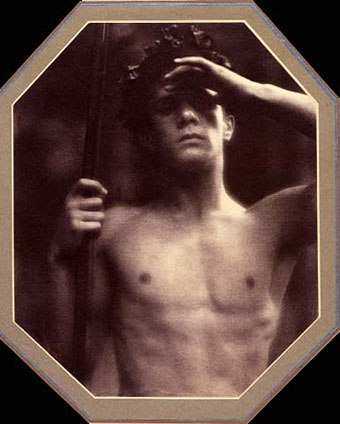

Devils and Angels (details).

Which disrespectful preamble brings us to another Italian, Lucio Bubacco, and his glass artworks. Bubacco is a Venetian and Venice has long been a centre of excellence in glass-blowing and sculpture. Yet Bubacco excels even by the standards of his birthplace, and his work is a deal more witty, imaginative and finely-crafted than the dull porn glassworks Jeff Koons had produced (by Italians also) for his Made in Heaven series in 1991. Of the work on Bubacco’s site my favourites are those in the “Transgressive” section which includes the marvellous Devils and Angels tableaux shown above, where a complement of masculine angels and demons are arranged about the central pillar in a Kama Sutra of celestial copulation. Not all his work is this outrageous, some is merely sweetly subversive like The Kiss showing an amorous encounter between a satyr and a naked man. That’s still enough to upset Falwell’s Puritan pod people but then they’re beyond our salvation, aren’t they?

• Official site | Lucio Bubacco on MySpace

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of ejaculation

• Czanara’s Hermaphrodite Angel

• Angels 4: Fallen angels

• Angels 1: The Angel of History and sensual metaphysics

• The glass menagerie

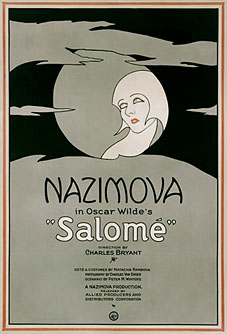

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or