Infinity Mirror Room—Love Forever (1966/1994).

Mirror, light bulbs, stainless steel, wood.

Narcissus Garden (1966/2002).

Watermall, 2000 mirror balls.

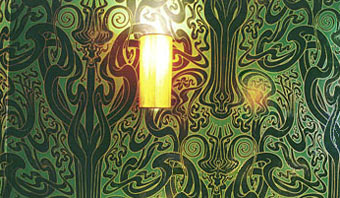

Fireflies on the Water (2002).

150 lights, mirrors and water.

Infinity Mirror Room, Rain in Early Spring (2002).

Since the late 1950s, Yayoi Kusama has used painting, performance, sculpture, and installation to develop a highly personal formal vocabulary that combines repetitive elements such as net and dot patterns with organic and often eroticized sculptural forms. Her early paintings and collages extend the language of Abstract Expressionism and its concern for allover compositions into an intimate form of gridded space.

By the early 1960s Kusama had begun to produce her Accumulations, everyday objects such as chairs, tables, and clothes densely covered with hand-sewn, phallic protrusions. Around the same time, Kusama began to paint net and dot patterns onto household items, and in 1965 she combined all these elements in the installation Infinity Mirror Room Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show). In Infinity Mirror Room a dense field of polka-dotted phallic protrusions extended from the floor of an enclosed space. The walls of the environment were lined with mirrors, leaving only a small passageway into the center of the installation empty.

For the installation Kusama’s Peep Show (1966), the artist constructed a room whose walls and ceiling were covered with mirrors, while the floor was densely filled with glowing electric lightbulbs in different colors. Two small windows allowed the viewer and Kusama to peer inside.

Continuing her obsessive, almost psychedelic approach, the installations suggest a kaleidoscopic mode of perception, in which interior rooms contain unbound, seemingly endless spaces. By the late 1960s, Kusama began to stage performances, sometimes covering her naked body, or others’ bodies, with patterns.

In the early 1970s, Kusama returned to Tokyo; she voluntarily entered a clinic for the mentally ill, where she has remained ever since. She has continued to produce work at a prolific rate, remarkable in its consistency. Her obsessive arrangements, her often radically eroticized alterations of everyday objects, her fascination with infinity, and the all-encompassing nature of her work have remained at the core of her production.

In her most recent works Kusama continues to create reflective interior environments. Fireflies on the Water (2002) consists of a small room lined with mirrors on all sides, a pool in the center of the space, and 150 small lights hanging from the ceiling, creating a dazzling effect of direct and reflected light, emanating from both the mirrors and the water’s surface. Fireflies embodies an almost hallucinatory approach to reality, while shifting the mood from her earlier, more unsettling installations toward a more ethereal, almost spiritual experience.

More information and pictures at her site.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Atomix by Nike Savvas