It’s easy to loathe the teeth-grinding sentimentality of Charles Dickens’ seasonal tale, as well as its subtext which isn’t so far removed from Emperor Ming’s instruction to his cowed populace in Flash Gordon: “All creatures shall make merry…under pain of death.” Yet as a ghost story I prefer A Christmas Carol to the sketchier The Signal-Man, and I’ve always enjoyed this memorable 1971 adaptation from the animation studio of the great Richard Williams.

Marley’s ghost.

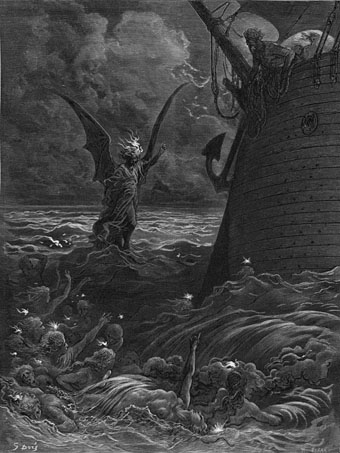

Williams is best known today for his role as animation director on Who Framed Roger Rabbit? but prior to this he’d distinguished himself as creator of the florid title sequence for What’s New, Pussycat? (1965), and the animated sections—done in the style of 19th-century engravings and political cartoons—for Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968). Williams’ Christmas Carol owes a similar debt to Victorian graphics, not only to the original story illustrations by John Leech, but also to Gustave Doré’s views of Victorian London, scenes which had earlier influenced the production design for David Lean’s adaptation of Oliver Twist. Williams’ film crams Dickens’ story into 25 minutes but nonetheless manages to maintain the tone of the original to a degree which eludes many feature-length travesties, especially those in which the nightmare squalor of Victorian London is reduced to a shot or two of dressed-down extras. Dickens had first-hand experience of the squalor: Kellow Chesney’s The Victorian Underworld (1970) quotes at length from one of the journeys Dickens took (under police escort) through the notorious St Giles rookery, and his ghost story was intended as much as a warning to the complacency of middle-class Victorian readers as a Christmas celebration.

The Ghost of Christmas Past.

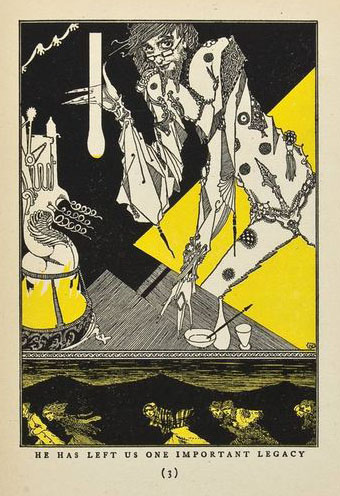

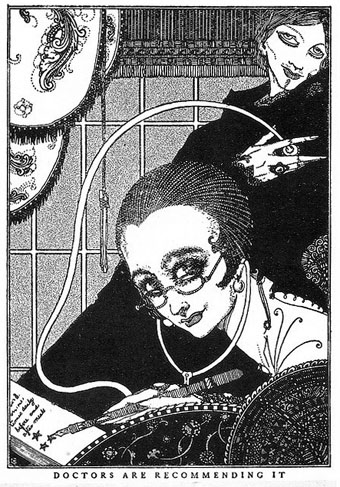

For me the crucial moment in any adaptation comes when the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge the figures of Ignorance and Want: in most film versions these tend to be a pair of well-fed child actors in rags and make-up; Williams shows us two grim spectres that owe more to Gerald Scarfe than Walt Disney. Williams is also truer to the ghosts themselves: Dickens describes Jacob Marley unfastening his jaw which falls open then remains that way while he proceeds to speak to his former friend; the Ghost of Christmas Past is the androgynous figure from the story with its ambiguous nature also shown by its shimmering indeterminate outline.

Ignorance.

Any animated drama relies on its voice actors, and Williams was fortunate to have Alistair Sim (as Scrooge) and Michael Hordern (as Marley) reprising their roles from the 1951 film version, while Michael Redgrave narrates the tale. The film used to be a seasonal fixture of British television, and may still be for all I know (I haven’t owned a TV for years). For the time being it’s on YouTube, of course, with a full-length version here that’s blighted by compression artefacts but is watchable enough. 2012 is the Dickens bicentenary so expect to hear a lot more about the author and his works in the coming year.

Update: The version linked to originally has been deleted. No matter, there’s a much better copy here (for now).

As usual I’ll be away for a few days so the { feuilleton } archive feature will be activated to summon posts from the past below this. Have a good one. And Gruß vom Krampus!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• “Who is this who is coming?”